This is where hard work got us (another post about the bad film)

This is the second in series on Planet of the Humans. The other posts are here:

Post 1 – on the myths and misunderstandings in the film

Post 3 – on the ‘bigger picture’ of the film, and why it’s harmful

Inwards-facing criticism is a tightrope walk on a knife’s edge in a hurricane. So it’s no surprise the new film from Executive Producer Michael Moore and director Jeff Gibbs, ‘Planet of the Humans’ was aggressively boosted by nearly every single major right wing climate denial group in the world, all grinning with delight to see their fading relevance rekindled by a left-wing god-king.

It is not a careful film. As I wrote in my previous post, it’s horribly wrong on most of its point on wind and solar power. This is a real worry, because it has been viewed millions of times. Michael Moore has more Twitter followers than Greta Thunberg, Bill McKibben and the Sunrise Movement combined. My Twitter mentions have been a constant stream of weird and not-wonderful climate change deniers. It’ll probably get worse before it gets better.

For now it’s time to try and recover from the destruction wrought by these guys. I want to write a follow up that properly explains where we are at now, when it comes to clean energy and perhaps briefly on the climate movement in general.

Things have changed a lot in the near-decade since Gibbs made his documentary. There are some good things, some surprising things, and some looming challenges. It was a hard decade, and every decade following will be harder. But there are amazing people working on unthinkably huge problems, and we are starting to see signs of progress.

Companies buying renewable energy is a good thing

In the film, Gibbs takes a swipe at Apple, the global tech giant, for professing to be running on 100% renewable energy, but still being connected to a dirty grid.

Obviously, it isn’t feasible for a large building to disconnect from the grid and obtain power solely from a single source. This is why when you make a new building, you don’t also build a tiny coal-fired power station next to it.

The way ‘x% renewable energy’ works is companies look at how much energy they consume, and buy from the grid the same (or some percentage) quantity of energy sourced from renewables. The grid is one big pool with buckets of energy in and out. This is a revelation to the filmmakers, but a boring reality for anyone remotely familiar with the mechanics of electricity grids.

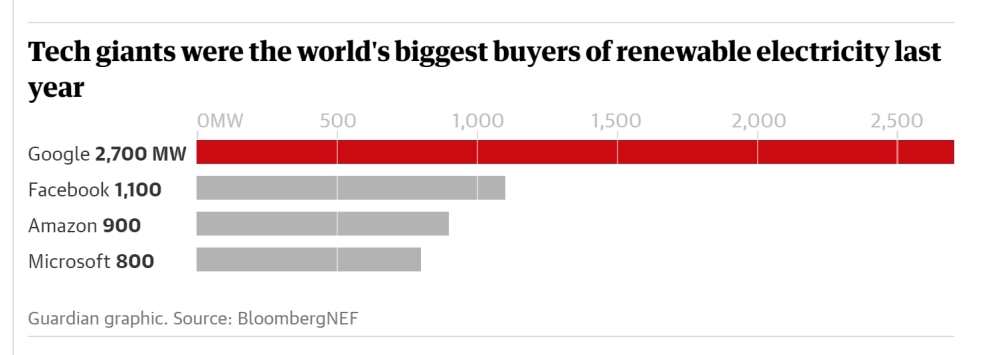

In fact, these agreements – ‘power purchase agreements’ or PPAs – have served an important purpose. Apple’s main competitor, Google, is easily leading the entire tech industry in purchasing renewable energy:

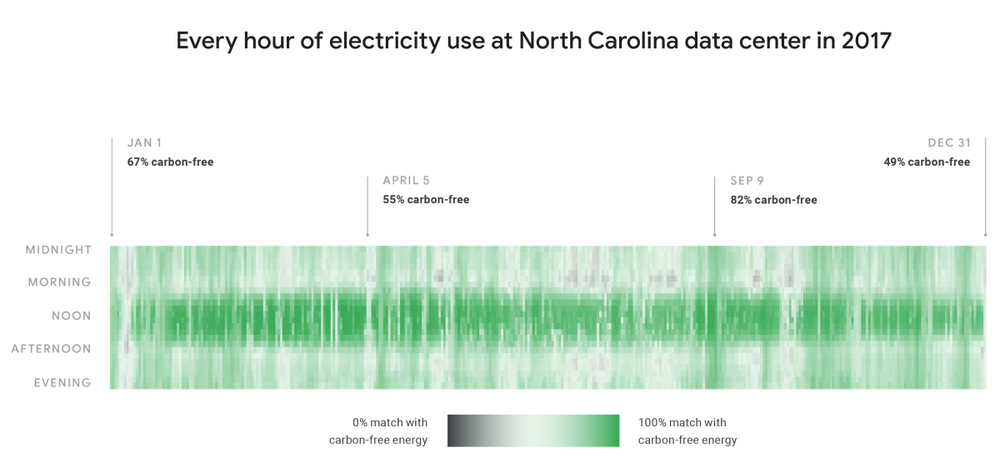

Google are unique, here. They make an effort to go beyond simply making the amount they consume match the amount of renewable energy they purchase. They sign deals with new projects only, and try hard to sign projects that are physically near their data centres. They are also trialling a tool to increase data consumption at times of high renewable output and decrease it during times of low, moving past the ‘megawatt hour for megawatt hour’ purchasing model, and going even further in attempting to maximise consumption of clean power:

Google are not pure, but they are doing a lot of heavy lifting in both encouraging new wind and solar, and accommodating its generation pattern. Broadly, corporate PPAs have become a primary part of the engine of climate action around the world. 2019 was the biggest year ever, and America leads:

It’s worth noting the dark side of corporate PPAs. I’ve noticed a trend of companies that extract fossil fuels attempting to lower the emissions footprint of the act of digging carbon from the ground. Of course, it’s ludicrous: those fossil fuels are still burnt later, no matter whether you power your coal mine with solar panels. Far too many corporations get away with using solar and wind in their marketing without substantially decarbonising their business. It makes me mad, and I call it out whenever I see it.

Here’s something fun. I was wondering why the filmmakers only mentioned Apple and not Google. I discovered that there is a reason: the filmmakers revealed on their podcast that they partnered with Youtube – owned by Google – for the film’s release:

“Youtube, last night, the people there gave us a call to share with us the analytics, the data. They were blown away. The first words out of the mouth were ‘these numbers are insane’….these people are so great, at Youtube. I can see why they got to who they became, and the service they provide for people….thank you people at Youtube for helping us with this debut” – Michael Moore

Google’s Youtube division cannot kick its misinformation and climate denial habit, so this seems like a perfect match. But it is fun to know that their anti-renewable film is hosted on servers that are powered by wind and solar. Not just in the ‘net’, buckets-in-buckets-out sense, but increasingly, in the literal, output-matched sense.

It is also worth noting that Google includes biomass in their definition of renewable energy (the target of most of the film’s ire). It is a little weird, for your anti-corporate, anti-renewable, anti-biomass film to partner with the planet’s fourth biggest corporation, one of the biggest customers of renewable energy and one that says biomass is clean. But hey, at least they’re participating in one of the biggest components of clean energy growth in the past decade. Good on them.

What renewables do to electricity bills

In my previous post, I said ‘[Renewables] do incredible things to electricity bills’, but I didn’t expand on that or even include a link, because by the time I got that far down I had a pounding headache and just want to snap my laptop shut and cry in a corner.

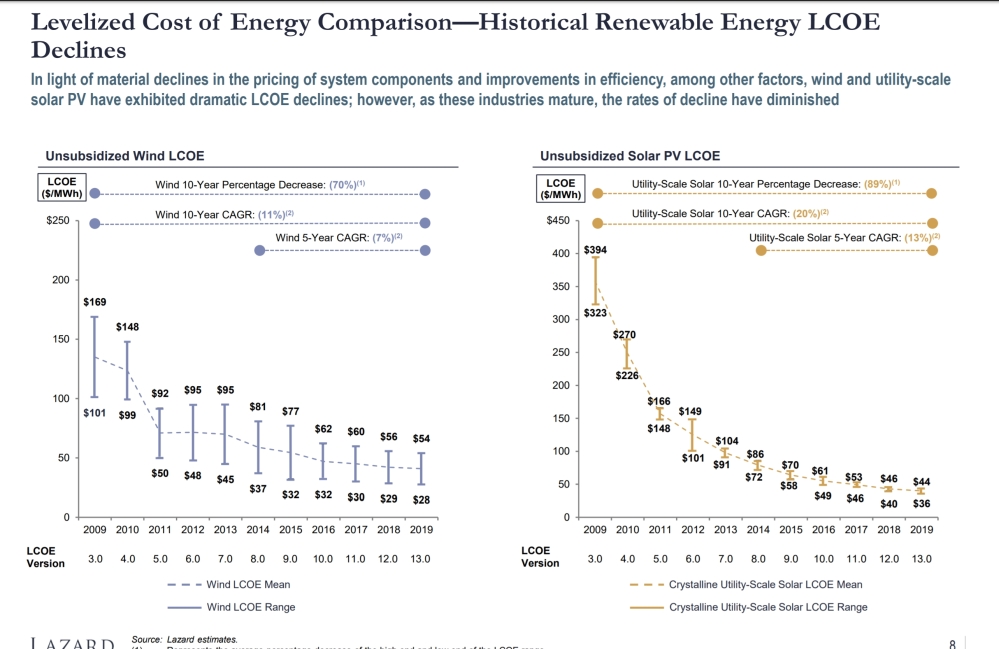

What I really should have said is this: when you source your power from the wind and sun, you pay less money. Back in the early 2010s, when this documentary was made, both wind and solar were more expensive, which meant they required subsidy schemes to be built – but in their operation, they were cheaper, pushing down prices in markets like Australia’s, in which a -5-minute bidding system sets wholesale cost (the ‘merit order’ effect).

For Australia, researchers recently found “that an extra GW of dispatched wind capacity decreases the wholesale electricity price by 11 AUD/MWh at the time of generation, while solar capacity by 14 AUD/MWh”. And the latest update from the Australian Energy Markets Commission, AEMC predicts a huge drop in bills due to growing wind and solar.

The positive impact of renewables on electricity prices is getting bigger because it isn’t 2012 anymore. Wind and solar are no longer expensive to build, which means the lifetime cost (‘levelised cost of energy’) is lower:

In Australia, the head of the country’s clean energy lobby group has explicitly stated that both technologies don’t need subsidies anymore. It is true in many other places around the world. When I saw that the clean tech world has changed since 2012, I mean it. Remember when ‘they need subsidies!!’ is all you’d ever hear? That chant has stopped.

It’s worth noting that the price suppression effect doesn’t last forever. A recent analysis of Australia’s future grid found that renewable energy only decreases prices if the policy settings are tuned the right way. But at a time when the broad assumption was that the dropping costs of wind and solar had hit a plateau, we keep seeing news like this:

Not only are people now in a situation where they’re either losing work or losing their jobs, their electricity bills will be increasing due to increasing residential demand (even as broader demand decreases).

Lower bills right now is an extremely good thing, and it sucks that for people to enjoy that, they’re going to have to fight Michael Moore, Jeff Gibbs and Ozzie Zehner.

Zero carbon energy is already killing coal

“The UK has this morning broken its existing record for coal-free power generation, surpassing 18 consecutive days and counting”, was a nice little sentence I read a few days ago. That country’s coal fleet has been declining rapidly, even though the country’s gas fleet has remained largely unchanged in output. As UK analysis outlet Carbon Brief’s Simon Evans explains:

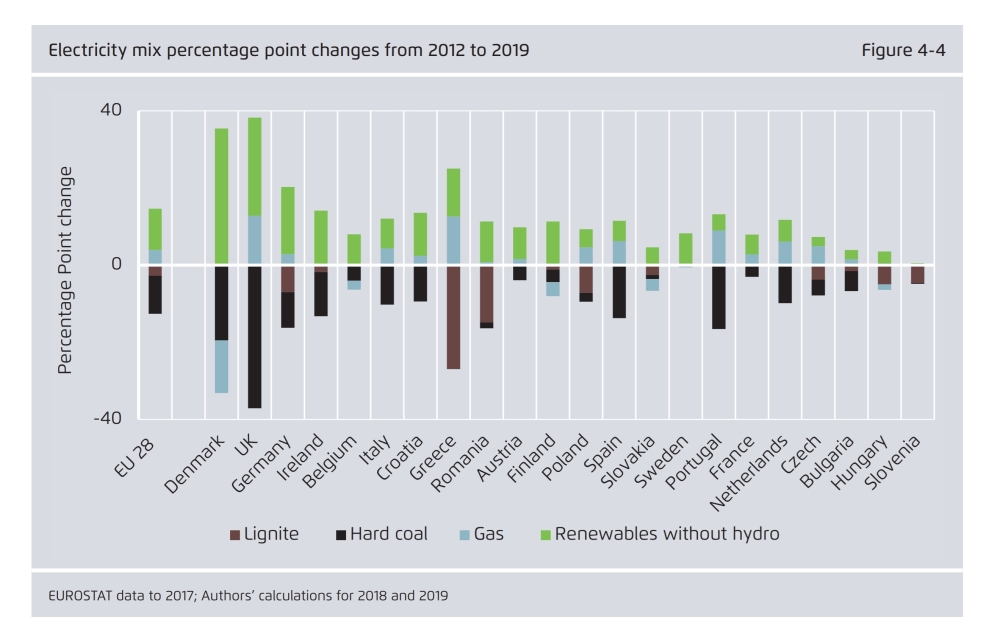

I mentioned South Australia and Denmark in my previous post, but it’s worth including Germany too (the filmmakers invented an entire fake gas terminal there, by the way) – another country with plummeting coal usage. Lower air pollution in the country and sunny skies have led to solar power output records, “exacerbating market forces that were already hammering the profitability of the country’s remaining coal plants”.

2019 was a disaster year for coal. The finalised data aren’t out yet, but all bets are on the biggest drop ever. The EU definitely had its biggest drop in CO2 emissions on record. This is partial success, and we are not anywhere near where we need to be. Coal may be wounded but the oil and gas industries are growing.

But it is something, and the situation would be far more dire without the effort that has gone into it. For the first time in a decade, the hard work of clean energy advocates, climate advocates and policy-makers is beginning to manifest in hard numbers, in pockets around the world.

‘Planet of the Humans’ does not like the idea that effort works. “This brief virus period in one week has done more than the environmental movement has done in 30 years to reduce consumption”, gloated producer Ozzie Zehner, on a US TV network. 220,000 thousand people have lost their lives, so far. It makes perfect sense that they’re glad for the pandemic, because their worldview is that it is impossible to work our way out of the curse of fossil fuels – hence, the happy reaction to the reduction in human life that pandemics tend to bring.

What we know is that new forms of energy technology that cause significantly less harm to humans and to the environment successfully displace the old, polluting ones. It is not easy, smooth or consistent, but it works. In some places, that is far advanced and in others, it’s only just beginning. It will be hard everywhere, but it is worth the effort.

Making renewables a fossil fuel killer, not just a coal killer

In the film, Gibbs walks into a random solar expo, and coaxes a bunch of obviously well-meaning exhibitors into talking about the challenge of intermittency.

Wind and solar generate according to resource availability, but demand (aka ‘load’) on a grid is predictable and has a solid ‘base’ (this is where ‘base load’ comes from). A few people in the film mention battery storage. This is is where you take a lithium ion battery (like the ones in the phones, laptops and cameras of the filmmakers), make it big, and use it to store energy.

These batteries are getting cheaper (cost is already half of what it was two years ago), but simply installing them at the same capacity as pre-existing fossil-fulled power stations is ludicrous. There are also real and important considerations about the impact of mining and extraction required to manufacture the batteries go into your smartphone, your laptop and commercial-scale batteries, alongside plenty of effort to reduce these impacts.

But like the generation of electricity, integration isn’t a single-technology game. To illustrate – Australia’s market operator has recently published modelling in which they simulated a future grid. They asked their computer to meet some demands. Make sure people got electricity above the grid’s performance standard, and make it cheap. As cheap as possible.

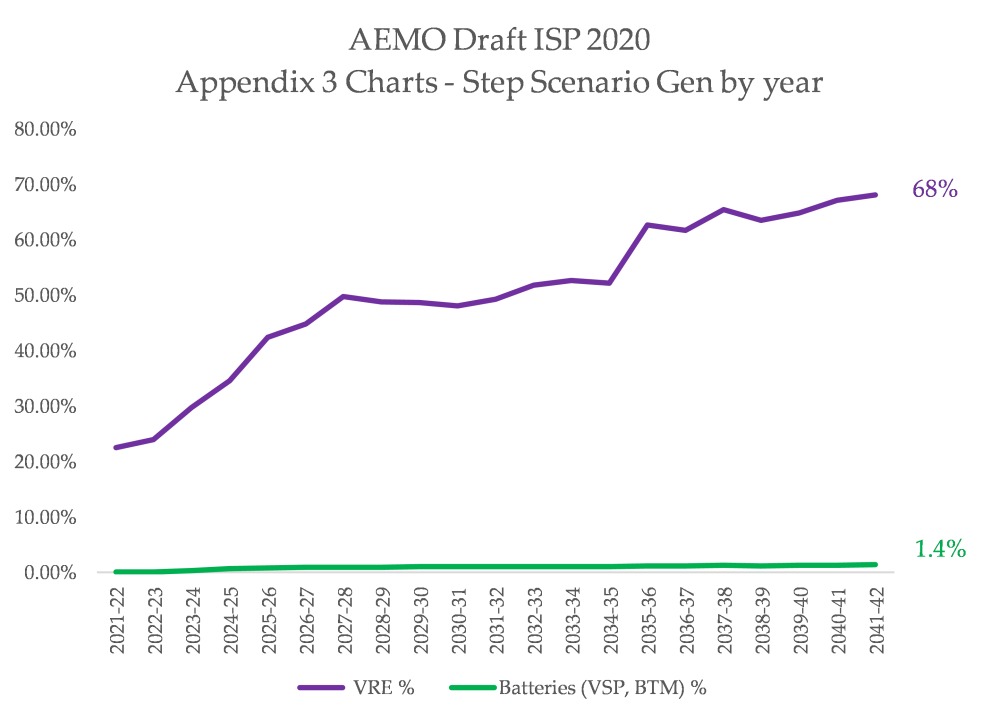

What they got, for their most optimistic scenario (in terms of emissions) was this:

Eh? What’s going on! The fillum told me batteries are the only way to make lots of VRE work!

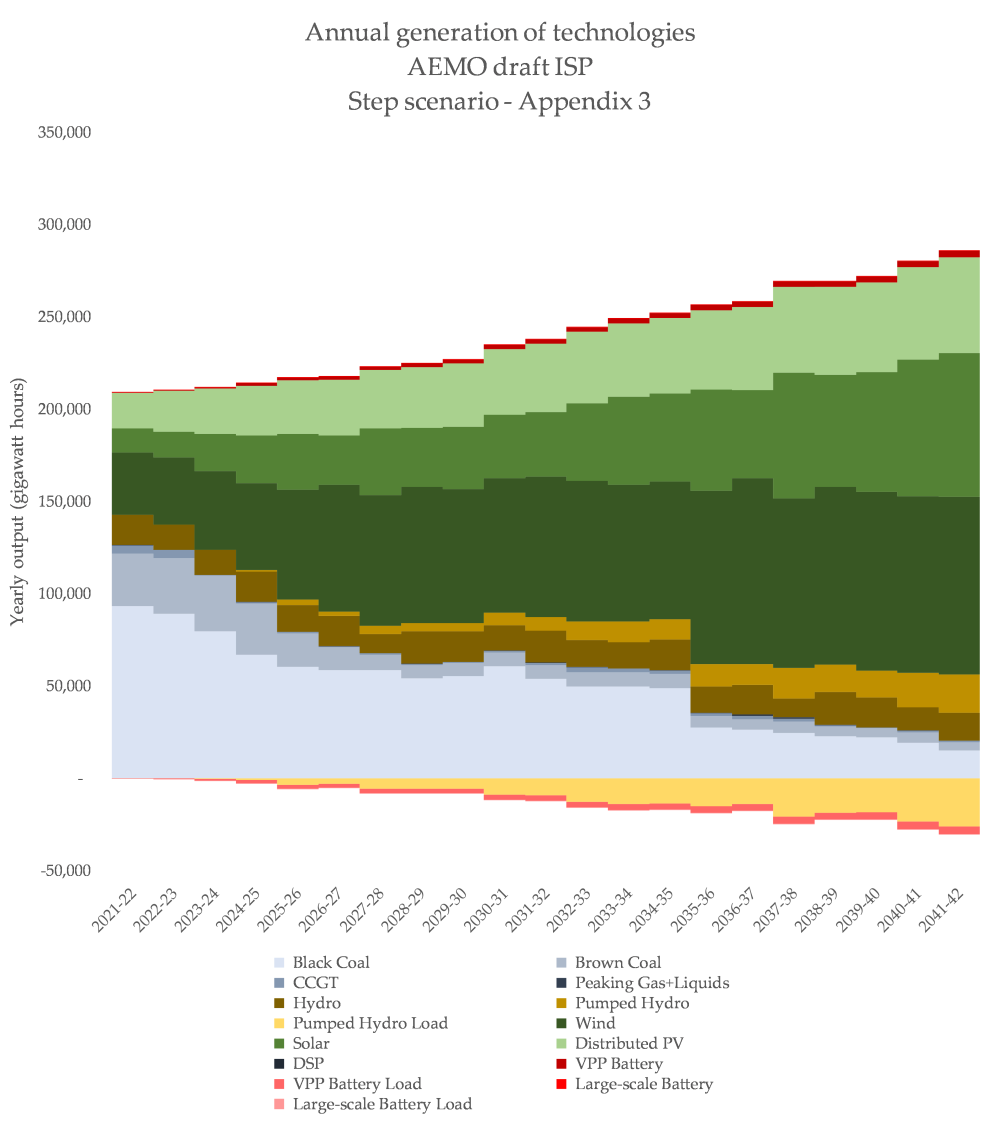

Well, no. You need a mix of things, and in reality that mix will change depending on a bunch of geographic, economic, political and social factors. In the grid operator’s (AEMO) model, these are the installed capacities of various technologies – like new interconnection, demand response, batteries (mostly distributed in ‘virtual power plants‘, VPPS, which involve home batteries ‘connected’ into one big one using software) that need to be built to replace retiring fossil-fuelled power stations:

Because wind and solar have become so cheap, it means a transition to zero carbon sources is the default option, even if you only set the two demands of (a) reliability and (b) cost. The final mix in the ‘optimistic’ scenario looks like this:

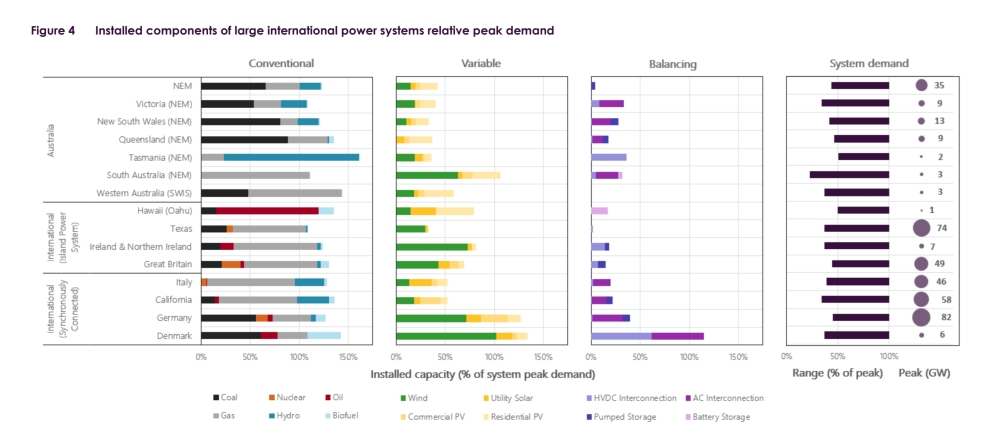

This modelling was recently expanded upon by the grid operator in Australia, in a huge, glorious ‘Renewable Integration Study‘. It is packed so deep with everything you want to know about this topic. They discuss peak penetration moments of 75% and 100% for wind and solar, by the year 2025. It’s feasible, they say, but it needs work. Hard work.

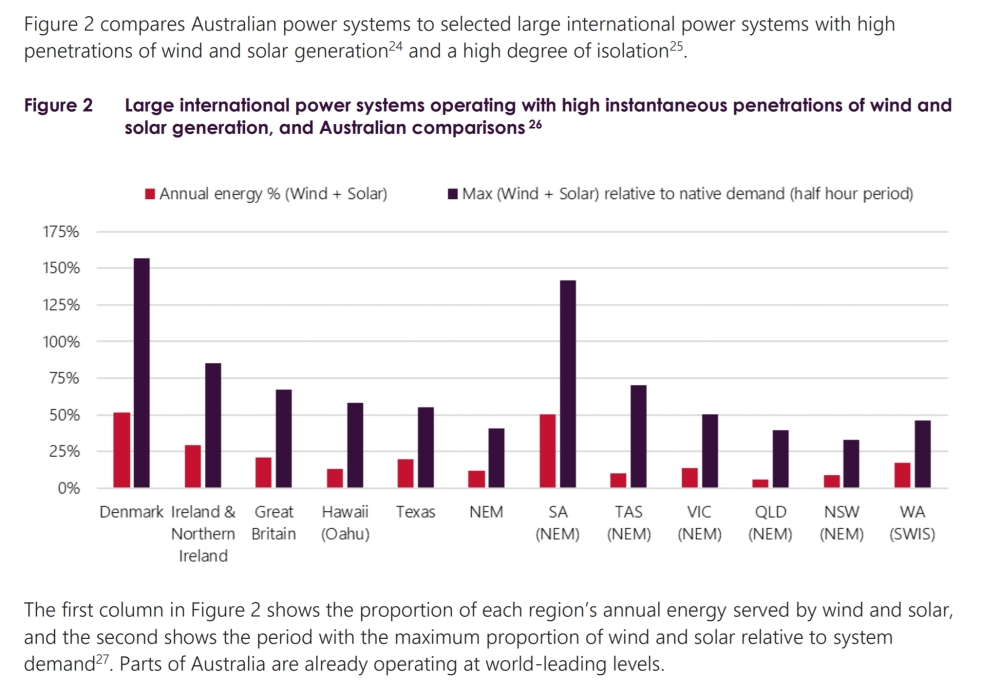

AEMO also include a great summary of countries around the world that already have high levels of variable renewables in their system. In my last post, I said:

‘“How much variable energy can a grid accept? Around ten percent, twenty percent tops it appears”, he wrote back then. I’d include examples of grids with higher percentages operating without a hitch today, but it feels almost cruel’

AEMO saved me the effort – here are a range of regions – both ‘islanded’ (not able to call on other countries using interconnectors) and connected into other regions – with levels of wind and solar well above 20%:

None of this has come easy, and the 2020s will be harder. There will be weird, new problems. There is a techno-social fight brewing in the heart of every single electrical grid, and that doesn’t even take into account the other sectors that create emissions, like agriculture and industry. Whatever form that fight takes, it is clear that the idea that work is meaningless is a toxic, evil idea.

Community energy

The poster for ‘Planet of the Humans’ features an anti-wind protester standing on the foggy, rocky construction site of the Kingdom Community wind farm, some time in 2011.

As I mention as an addendum to my previous post, that site has ended up being a relatively good neighbour to their community, handing over tens of thousands of dollars to local regions and running booked-out wind farm tours. It also looks nothing like the Stephen-King-misty-hell depicted in the film. But I wonder if the protests in its early development would have been so intense if they’d allowed for direct local ownership of the wind turbines.

Going off my own experience in the clean energy industry, some of the worst run-ins between developers and communities were, at least partly, impacted by the fact that the benefits of clean energy were not being evenly spread across the places that hosted it.

Many projects featured generous community contributions (like Kingdom’s), allocated through a committee, and many others employed many locals and sourced goods from local businesses. But it is not quite the same as community ownership, like we see in countries like Denmark and Germany, both of which lead the world in the proportion of renewable technology owned by citizens rather than corporations.

I am very optimistic about the potential for clean power over the next decade, but I am deeply freaked out by the possibility that wind, solar, or both could end up being as hated as nuclear power is, because it is developed in a fundamentally clumsy and anti-community way. As I mentioned above, many countries will need expansion of transmission networks to accommodate wind and solar – something being badly botched right now in Germany, due to community backlash.

The next decade of clean energy development will need to rapidly refine models of ownership. In countries where public ownership and citizen participation is prioritised, the growth of renewable energy has burgeoned. Corporations play a role in construction and in partnerships, but people take the lead. There is already a wealth of knowledge about community owned grid integration projects too, such as community storage projects, in addition to household-owned batteries acting as single, aggregated power plants.

Every experience I’ve had with community energy projects has been great, and every single person I know working in community energy has the warmest, kindest soul you can imagine. They are good people who work hard, and they are doing a lot to actually address the stumbling blocks of clean energy, pushing hard towards a more equitable, sustainable development. Not only do they have faith in human life, they prioritise people as the core of decarbonisation.

The people who will still be alive when we’re dead are working harder than all of us combined

One of the starkest moments of how truly disconnected these filmmakers are from the present day came during an interview with Michael Moore, where he said:

“We need a new environmental movement, we need young people to essentially take over. It’s their future”

If only a Swedish teenager would spark the fire of a global, youth-led climate movement that would culminate in the largest marches ever held around the world! Oh well.

After a pandemic (one that Moore horrifically frames as ‘mother nature sending us to our room’) shut down climate marches, it must be extremely infuriating to be told that the world needs a youth climate movement. It is telling that the film didn’t feature a single young person or climate activist and didn’t mention youth-led movements.

Compare that to Bill McKibben – the filmmaker’s main target – who frequently ‘passes the mic‘, in his newsletter for the New Yorker, to young climate activists. There is a way to be both effective but to also cede ground to people who lack it.

“Perhaps the most insulting thing is that this film comes at a time when the youth climate movement is finally gaining momentum. Young women like Greta Thunberg and Varshini Prakash have helped climate change break into the mainstream. Rather than bolster the work of the Sunrise Movement, Fridays for Future, or Zero Hour, it undermines these activists’ achievements by sowing confusion and doubt” – Professor Leah Stokes, UCSB

Again. Effort. The work that’s been put in to date has been immense, and it resulted in massive changes in public opinion on climate change (which will hopefully survive the pandemic).

Ensuring that decarbonisation goes beyond technocracy and into the realms of justice, equity and fairness is work. Climate action still lacks awareness of racism, of colonisation, of wealth disparity and of all the societal wrongs that created the climate problem in the first place. But like the technological successes I mentioned earlier, effort brings results in this social aspect too. Work has impact. America is definitely leading the world, with the creation of the Green New Deal.

The fundamental message of Planet of the Humans is anti-effort. It is, of course, weaved through its construction, with my last post on the film focusing on it being inherently lazy. But it also aggressively attacks people who are trying, without any familiarity of what it’s like to try. It is an attempt to fix climate change purely by yelling randomly blurted talking points from the sidelines.

No one knows where we will land, post-pandemic, in the context of climate change. All we know is that the risks of a massive rebound in emissions are huge, and the risks of fossil fuel companies soaking up stimulus money are big too. Even ‘clean stimulus’ has to be paired with considerations of a just transition, and a keen eye for fairness and equity, instead of buzzwordy promises of economic growth.

Even more work. But there are millions of smart, clever, keen people ready to do it. If you see one of these people, make sure you tell them they’re doing it right.

Read the next post in this series here

Thanks for this breakdown, Ketan. Onya.

LikeLike

Great insights and real updates on the RE progress and it’s challenges. Thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This second (and even longer) effort reminds me of Barbara Tuchman’s thesis in The Guns of August , i.e. that most humans, when faced with incontrovertible evidence, will resist changing tack and instead will double their efforts to prove that they were right in the first place, thereby exponentially increasing the severity of the nasty consequences. Michael Moore had the courage to follow the evidence wherever it would lead, as this author so obviously would not.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Michael Moore had the courage to watch Gibbs film a bunch of segments in 2009-2012 and then not do any research to see if they were representative of the renewable energy industry or climate change movement in 2019 when they released the film. He then had the courage to negotiate a deal with Youtube to release the film and single out Apple’s claims about renewable energy, but not mention YouTube’s parent company Google, which makes identical claims to Apple’s.

LikeLike

For any being who truly and wholeheartedly believes in what they are doing, whatever that may be, honest, constructive criticism and being open to that, is the key to the endeavour. If you close your mind to constructive criticism, then you cease to grow and achieve.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your critique of the film and your analysis of renewable energy. I agree with your criticism of the film in terms of its misinformation about renewable energy, and its misrepresentation of and harm to the environmental movement. But there’s one important message from the film which you have missed – not surprisingly, because the film it made it so badly. The point is that switching to renewable energy is simply not enough. We have to drastically reduce our consumption in order to avert environmental collapse, including – but not limited to – severe climate change.

While the film portrayed solar panel and wind farm production as if they were forged in the fires of Mordor, it did have a point – large scale production of renewable energy does have an environmental cost. Biomass can cause deforestation or replace vital food production, large scale hydro causes large scale environmental hard of entire river catchments, and so on. Maintaining consumptive lifestyles in the global north, alleviating poverty in the global south, and keeping our environment and future safe simply don’t work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The movie did get stuff wrong about solar and wind energy production but it is clear that with green energy alone we will not be able to turn climate change. Yes, we need clean energy in stead of fossil fuels but that’s only part of the solution. We need to do much more.

We need to cut down on consumption (for instance of cars, we need to go from car ownership to public transport for all combined with car sharing). We need to be content with what we have and not crave for what others have.

And we need to take on population control. One human less on this planet is a human not eating meat, not driving cars, not needing heat not making babies. And that’s not a racist or patronalistic thing. No, it’s a necessity.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“A few people in the film mention battery storage. This is is where you take a lithium ion battery (like the ones in the phones, laptops and cameras of the filmmakers), make it big, and use it to store energy.”

Oh dear.

Didn’t get the old meme-o?

Aug 2016, Australian Chief Scientist Alan Finkel:

“Imagine if you took all the lithium-ion batteries produced in 2014 for phones, laptops and cars and instead used them to provide backup for the global electricity supply.

They’d keep the world running for just nine seconds!

https://cosmosmagazine.com/technology/scale-and-a-new-favourite-number

Care to update that storage ability?

But seriously Ketan, how many solar panels does it take to “safeguard the planet” and prevent a drought?

“At UN Environment, we believe that sustainable energy presents an opportunity to transform lives and economies while safeguarding the planet.”

Why does energy matter?

https://www.unenvironment.org/explore-topics/energy/why-does-energy-matter

It’s the worst apocalypse. Ever.

LikeLike

Thank you for your informative posts in pointing out so many flaws in this film. I watched it. I couldn’t believe Moore put his name on it. I waited for some interviews with the filmmaking team to find out what they had to say about the criticisms. Their answers were highly enlightening. It is as if they have been in a basement somewhere for the past 10 years editing this film while completely ignoring the movement and activity on the surface. It is the only plausible explanation I can come up with.

LikeLike

Looking at that LNG port, I know that British Columbia is building at least one and those mountains in the background look familiar.

Also on the topic of natural gas, BC converted all our thermal plants from coal to natural gas years ago, so we’re more up to date than Gibbs and Moore.

LikeLike

Just because people say wind and solar are cheap, it doesn’t mean they are. Here’s some data. Offshore wind energy in the UK remains at 3-4 times the cost of electricity from gas. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301421518308504

Net zero will be an economic disaster.

LikeLike

So many times I read articles and cannot find any useful facts. Thank you for providing such useful facts. There is another place I found useful information https://conservationconstructionofdallas.com/dallas-home-windows/ and I think people could also get some useful information here. I can’t wait to read more. I’ll definitely be back daily to see what new info I can learn from your website.

LikeLike