Minimum Something (Part 2 – Safeguard)

Navigation

- Part 1 (Introduction and Targets)

- Part 2 (Safeguard)

- Part 3 (Transport and Power)

- Part 4 (Exports and Conclusion)

- Full Version

Audio files here, or visiting Soundcloud, here.

The Safeguard Saga set a grim precedent

In the Hunt / Abbott years, a policy known as the ‘Safeguard Mechanism’ was created. ‘Baseline’ emissions caps are set for the country’s highest polluting industries, but those caps float magically high above actual emissions – and the caps rise, if emissions rise. It was shameless, but it didn’t need to be. It could’ve been a 100 page PDF filled with capybara photos and it would’ve done the same job.

For 7 years, the Safeguard sat collecting dust. High-emitters pointed eagerly at it whenever the threat of regulation was raised. See? We’re already regulated! We’re doing climate action!

At some point, an idea formed – what if the policy could be transformed into something with teeth? What if the caps actually fell, and the ceiling began to ratchet downward on companies that had been letting their emissions free-float unchecked?

It’s a foolish idea. Trying to create good climate policy from something designed, from the ground up, to be fundamentally shit, was always doomed. As I’ve written in RenewEconomy (and in a million tweets), Labor’s new version of the Safeguard Mechanism is unsurprisingly bad. It’s a regulation that fails to regulate. It is more like mandated greenwashing. Yes, sure, companies have to buy offsets if they don’t reduce emissions – but those offset purchases can be used to falsely present climate action in their annual reports. By paying a pittance to fake climate action, these companies benefit from breaching their target.

This is really important. They are not compelled to reduce emissions – they are compelled to buy Australian carbon credits. They can reduce emissions instead, if they’re in the mood. But they don’t ever have to.

It’s packed with loopholes. There is no ratcheting limit on offset. The scheme features ‘intensity’ targets and internal credit systems that will likely incentivise more emissions. It performs the same action-delaying function as the old Safeguard, but instead of just being quietly shit for seven years, modern pressures of climate scrutiny means it has to perform a loud melodramatic interpretive dance of formulas and caveats and calculations and jargon.

Carbon offsets are the superstructure of this mess. Safeguard will feign success, but it’ll mostly be off the back of carbon offset purchases rather than real reductions. Falsely, and fraudulently, both the fossil fuel industry and the carbon market industry claim that buying an offset where someone has avoided emissions counts as a total neutralisation of releasing greenhouse gas emissions.

I say this a lot, but it bears repeating: this is completely bonkers. Paying for less harm elsewhere doesn’t neutralise the harm you cause. Carbon neutrality is mythical. Offsets are financialised fantasy. Even with zero fraud and 100% integrity, the entire system is based on a logic that would be immediately rejected, were it to appear in any other segment of human society.

Roughly half of the emissions covered here come from coal and gas mining, both industries that would disappear in a puff of logic if they ever stopped believing in their own eternal growth. Coal has plenty of planned mines, but the likely default outcome is slow shrinkage. Gas, on the other hand, has a collection of psychotic carbon bomb projects gaining real steam. These alone will instantly vaporise the over-complicated equations and budgets of this policy.

Being able to use a tiny, tiny fraction of their super-profits from just one year to remove the grinding contradiction of their expansionist fantasies and climate goals? It’s perfection, for them. Woodside, the second largest emitter in Safeguard has already announced they will meet all of their decarbonisation to 2030 using offsets. Amusingly, they released their climate report, in which they faked reductions using offsets purchases (when emissions really rose), right in the midst of the Safeguard debate.

There’s a simple reason this policy is so bad: the reforms were designed by the fossil fuel industry. I thought their footprint was nicely illustrated in the government’s own reforms paper, which I discovered featured fossil industry lobbyists far more than any other group, in quoted responses. Of the non-fossil groups, business lobbyists and consultancies were the next biggest. 6% of quotes are from climate groups.

In February 2023, think tank InfluenceMap detailed the timeline of industry demands, and subsequent implementation by the Labor party. These include:

- Capping the price of carbon offsets, and letting taxpayers pay the difference, to ensure greenwashing and fake regulatory compliance don’t become too expensive (a secondary effect is that guaranteed cheap offsets will ensure no company is tempted to actually reduce emissions instead).

- Oil and gas industry associations demanded that high-polluting international traders be allowed a weaker decline rate in their cap. The ceiling drops far slower, for them. When you sell stuff overseas, your emissions count less, somehow.

In October 2021, the Business Council of Australia, which features several major polluters as members, published their ‘Net Zero’ guide. Really, it was more of a list of demands. Their key demand was the creation of a kind of limited-edition carbon offset. When a company sits below whatever its emissions cap is, it gets credited a reward, the size of which depends on how far below the cap you are. If you’re above, you get penalised. These rewards can be traded by companies below to those above, for a market price. The hard physical reality of climate change meets the fuzzy pseudoscience of economics.

Of course, these special ‘Safeguard credits’ will have their own array of problems. Given that the baselines are based on ‘intensity’, and not absolute emissions, that means a polluter with rising emissions could end up being granted lucrative credits, as long as their ‘intensity’ falls. The concept only works if baselines make sense, but the industry has won an absurd array of complex loopholes in the setting of those baselines, so it’s destined to be an ever-worsening mess.

There are far better ways to tackle industry emissions, without ever needing offsets. Germany just launched a massive new subsidy program called ‘carbon contracts for difference’ that uses cash handouts to companies to compensate them for the increased cost of reducing emissions. That is in itself a reaction to the massive US ‘Inflation Reduction Act‘, again a generous subsidy scheme (notably absurd was the Labor Environment Action Group declaring Safeguard was more significant than the IRA). Though both the US and Germany are failing to tackle fossil extraction like Australia, these policy designs are a million times better than Albo’s worry-free offsetting bacchanal.

Perhaps the biggest demand of the fossil fuel industry is yet to come. Most polluters in the scheme want it opened up to international carbon credits. Somehow even more controversial than Australia’s deeply suspect carbon market, international credits have undergone a near-weekly drumbeat of scandals, revelations, frauds, corruption and deception, this year.

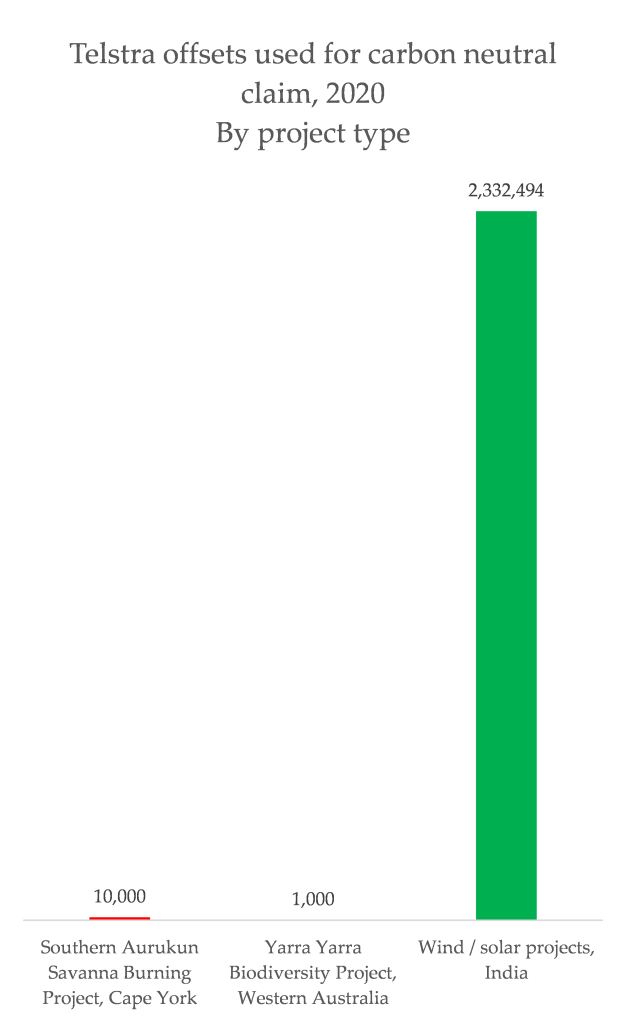

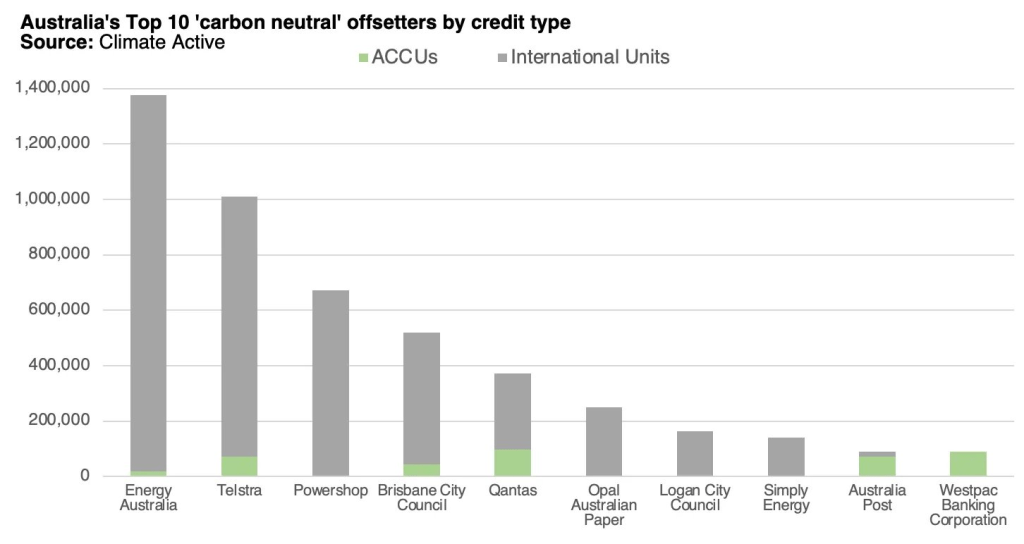

Corporations in Australia like international credits. They’re cheap, because they’re dodgy, so they can pad out the bulk of purchases. Companies will then buy a little smidgen of Australian offsets and feature these most heavily on their comms materials. Telstra, for instance, features 429 words on their Australian offsets on their webpage, and 96 on international. They purchased 11,000 tonnes in Australia, and 2,332,494 from overseas. Those offsets are used for the company’s activities, which include selling fossil gas to homes that should be electrified, instead.

As analyst Michael Mazengarb found, the majority of voluntary offset purchases in Australia come from cheap, dodgy international suppliers. Opening the Safeguard Mechanism up to international credits would update the scheme to be in line with best-practice greenwashing and faked climate action across Australian industry.

Most recently, Chevron was revealed to have purchased most of their carbon offsets from projects that were fraudulent, impinging on human rights, or both. This is what Chevron had to say about Safeguard, a few days ago:

"Chevron was supportive of the Safeguard Mechanism. We do have some concerns around longer-term access to carbon offsets. Our preference would have been for the Safeguard Mechanism to be open to using international offsets along with Australian Carbon Credit Units"

Oh, Chevron. That’s cute. You don’t need to ask, sweetie. The government is going to make it happen for you. “We also welcome the government’s commitment to further explore the use of international credits”, the Business Council of Australia said. You see, they know it’s a matter of time. The government is proud of these relationships.

“Our plan to fix the safeguard mechanism has been endorsed by industry and business—Origin, Rio Tinto, Shell, Woodside, the BCA, the Australian Industry Group, ACCI, the National Farmers Federation and the Minerals Council”, Anthony Albanese proudly proclaimed in parliament, in February this year. This isn’t a new thing; Albanese has seen the endorsement of the worst emitters as a mark of pride for quite some time. Bowen, too.

Labor’s changes were mostly easy adjustments, but the Safeguard Credits bit had to be legislated. That means getting the support of the Greens – who threatened to block the passage of the reforms if the government didn’t push back on coal and gas mining expansion. In most media coverage, discourse and political debate, the majority of the opprobrium was directed at the Greens for the unforgivable act of demanding better policy, rather than at Labor for proposing bad, insufficient policy. Labor knew from the outset the centre of gravity in Australia’s business, media and political institutions sits at climate delay and pro-fossil greenwashing.

Frustratingly, Australia’s left-leaning media institutions and even quite a few climate groups and NGOs felt the best course of action was to critique the details, but to never support the concept of blocking the policy until it was improved. Groups like the ACF and the Climate Council had good, strong demands for reform, but refused to support the Greens blocking bad policy.

The Labor party and their allies in media outlets scandalised the Greens using their balance of power to block bad, greenwashing and counter-productive climate legislation. The underlying assumption was that something was better than nothing, and that blocking that would make the Greens no better than the conservatives. Of course, government mandated greenwashing could easily end up actively worsening emissions than if nothing were passed at all, but this was fundamentally tuned out of the discussion.

It worked. The Greens quietly agreed that they were politically unable to block Safeguard, and they only ended up winning relatively weak changes to the scheme. If a company uses more than 30% offsets, for instance, it has to write a letter explaining itself. I’m sure Woodside is trembling with fear. There is also “a limit on gross emissions, so that from 2024, 5-year rolling average emissions must go down”. Cool. So we’ll have our first data point in 2029. That one is the only emissions “cap” that doesn’t count dodgy offsets in the numbers.

Each amendment is response to failure, rather than a change that prevents failure – and each amendment relies fully on the good sense of the minister at the time, rather than being set down in hard law.

One hell of a return on investment for the fossil fuel industry, who in 2021-22 donated the most they’ve ever donated to the Federal Labor party.

Labor, when threatened with the possibility of actually reducing emissions through a strengthened emissions regulation scheme, fought with bloody cunning to protect the fossil fuel industry, and to protect themselves from having to own and enforce real climate action. The standard has been set: though the Greens hold the balance of power in the senate, they cannot use that power to beat shitty climate policy into shape.

Media institutions and even some climate groups have helped that along. A party that will only act on climate change when bullied, forced and pressured into doing so has demonstrated that it can stand up to being forced into taking real climate action.

This is bad, because in the transport sector, there remains quite a lot left to lose.

- Part 1 (Introduction and Targets)

- Part 2 (Safeguard)

- Part 3 (Transport and Power)

- Part 4 (Exports and Conclusion)

- Full Version

Comments are closed.