2024 CCS update: the revolution refuses to arrive

It is bad enough that 2024 was a record high for global greenhouse gas emissions. It is extra-bad because the number we’ve ended up at is higher than all of the old projections of what this year would end up at. That is to say: we are underestimating our ability to stop using fossil fuels.

There have been incredible advances in renewables and climate policies, but also, “fossil fuel subsidies remain at an all-time high and funding for fossil fuel-prolonging projects quadrupled between 2021 and 2022”. Why? What is justifying this weird refusal to back away from the fossil fuel economy?

It’s many things, but a big one is the false promise of a machine that cleans up fossil fuels, rather than us needing to find a replacement for them.

Back in 2022, I contributed an essay to Greta Thunberg’s Climate Book. It was about the weaponised false promise of carbon capture and storage (CCS). I wanted to talk about it not as a technological phenomenon but a rhetorical one. A tactically deployed promise that is never meant to come true. Failure as a feature, not a bug. I’ve since written two update posts, here and here, expanding on that analysis, and it’s time for the annual update.

The second coming hasn’t come yet

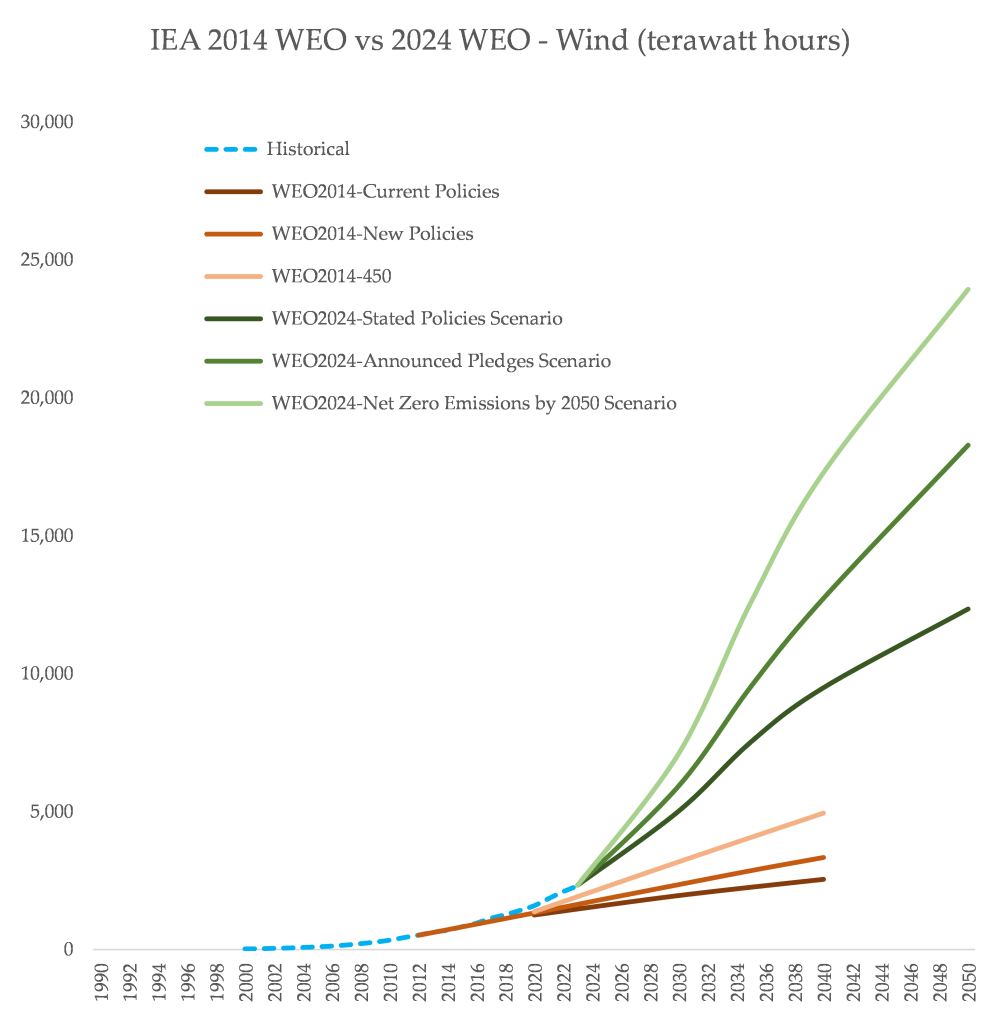

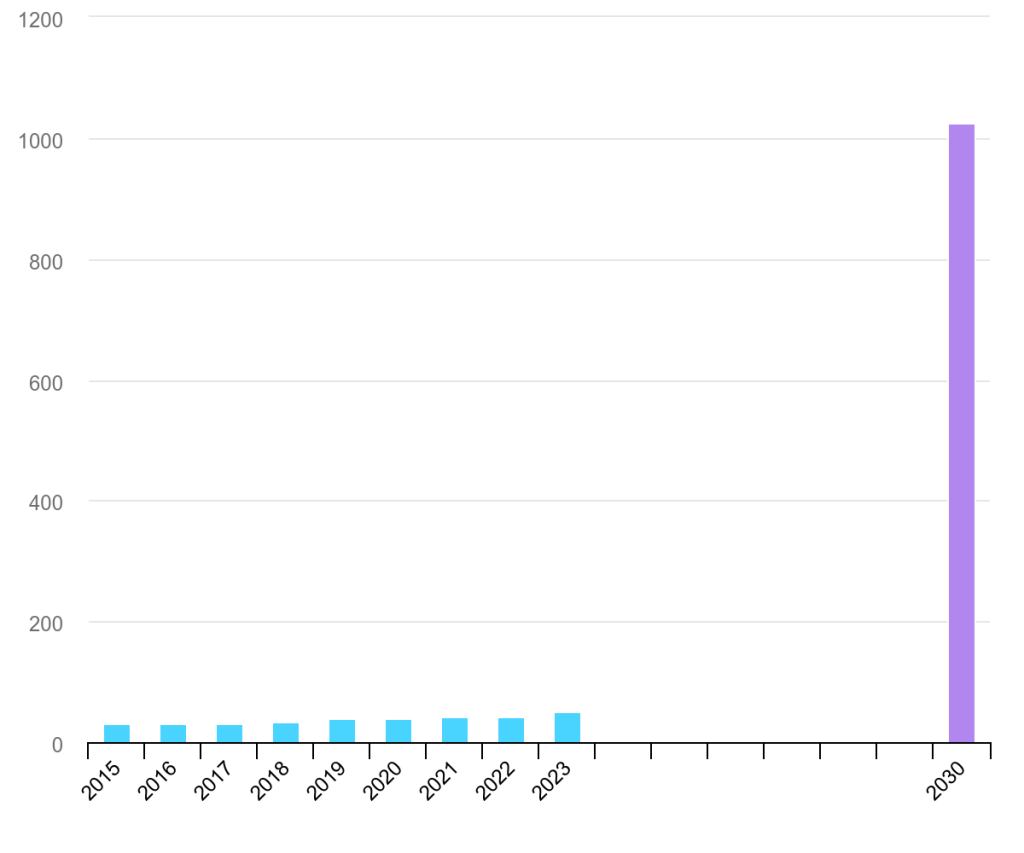

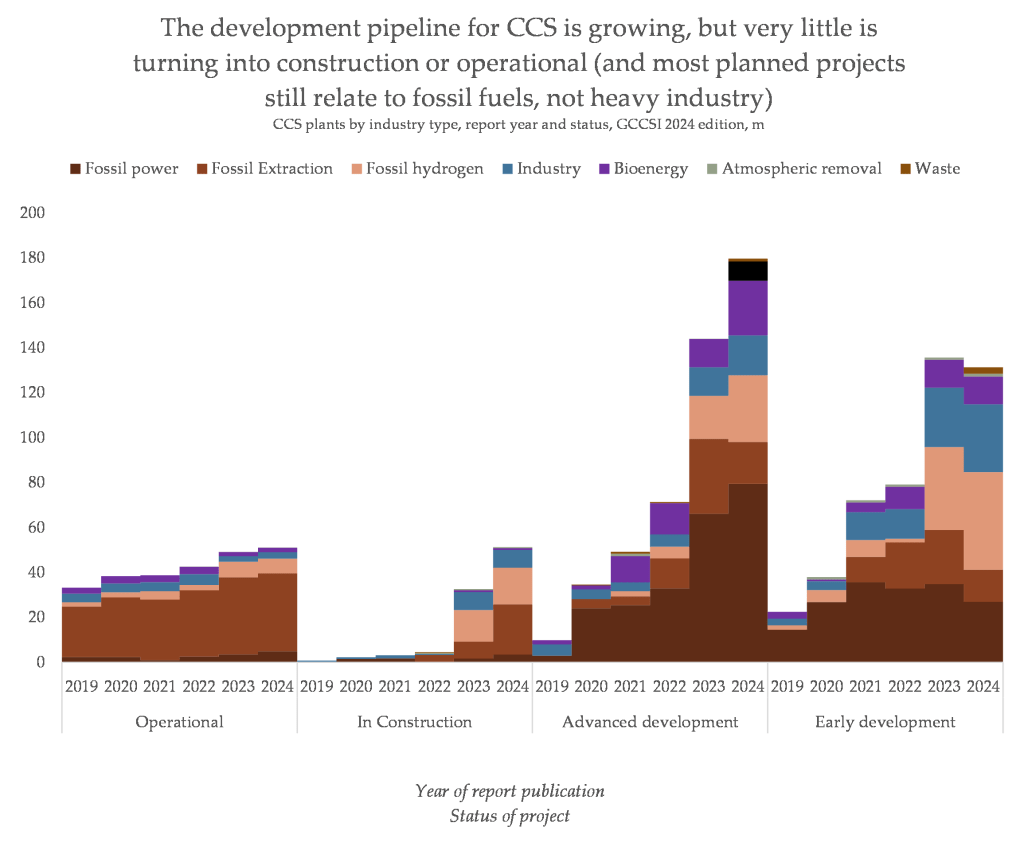

After a surge of planned projects in the late 2000s and early 2010s failed to turn into operational carbon capture sites, there was a lull. But since 2020, the volume of planned CCS has increased very significantly, as we can see from the latest update from the ‘Global CCS Institute’, a CCS reporting and advocacy group that publishes annual data:

As with so many previous years, the change in ‘operational’ CCS is small. The pipeline for CCS has been surging for a half-decade now, and the amount of operational CCS has only grown by a few megatonnes of capacity. We were promised a CCS revolution, and we aren’t getting one.

Each year’s database puts an estimated ‘start date’ on these CCS projects, so if we compile every report from each year, we can get an idea of what should be operational, and compare it to what is:

In 2024, the amount of operational CCS should be several times higher than it actually is, based on the promised start dates of projects in older reports. Some projects are being cancelled, others are pushing out those dates further into the future due to frequent delays. Carbon capture isn’t a technology that likes to be built.

It’s almost a cruel1 chart to make, but compare the percentage growth in operational CCS to the growth in wind and solar over the same time, and you get an idea of the different dynamics we’re dealing with here:

Why do we keep believing the promise when it keeps failing to materialise? There are many reasons, but I want to dive into a specific one in this post: a range of different future scenarios, from a range of different sources, has leant hard on CCS as a way to minimise projected reductions in fossil fuel use, and therefore politically soften any potentially scary visions of the “disruptive” elimination of fossil fuels.

What the future looks like

As I detailed in previous posts, fossil fuel companies (both power generation and extractive) love using the false promise of CCS to justify massive, high-emitting projects. It’s worth diving into this incredible July 2024 investigation by Drilled’s Amy Westervelt, specifically on how fossil fuel companies were actively aware that their promises on CCS were hollow.

Fossil fuel companies have, for a long time, performed a sort of strategic science fiction exercise, where they publish fossil-heavy and CCS-reliant scenarios to try and own the space of what the future looks like.

Using the data made available in the latest ‘Resources for the future’ Global Energy Outlook, I’ve made2 a little illustration of how fossil fuel companies use assumptions about CCS in their scenarios that are weirdly disconnected from the material realities of ultra-slow deployment:

Equinor, my friendly local state-owned fossil fuel company, are comfortably the worst offender here. From 2018 to 2021, their CCS projections were verging on possible. In 2022, 2023 and 2024, the 2030 assumptions for CCS are deeply bonkers and far exceed Shell and British Petroleum’s assumptions. This is despite Equinor being notably off track even for their own company CCS targets3.

Consider the International Energy Agency’s ‘World Energy Outlook‘, a major annual global energy system model, whose future scenarios drive investment decisions and government policies.

This year I’ve created a compilation of each year’s recent CCS assumptions in their most-ambitious ‘net zero’ scenario, and you can immediately see that as far as CCS is from even realising its own pipeline of planned projects, the gap between the assumptions in the IEA’s net zero scenario is significantly worse:

If CCS development were truly following the IEA’s 2022 net zero scenario, operational capacity today would be about twelve times what it ended up being this year. The IEA’s 2024 scenario, released a few weeks ago, assumes that CCS capacity will be around 25 times greater in 2030, than it is today.

It’s worth acknowledging the IEA can be circumspect about this. Their 2020 ‘CCUS’ report looked back on an old ambitious scenario:

“CCUS deployment tripled over the last decade, albeit from a low base – but it has fallen well short of expectations. In 2009, the IEA roadmap for CCUS set a target of developing 100 large-scale CCUS projects between 2010 and 2020 to meet global climate goals, storing around 300 MtCO2 per year. Actual capacity is only around 40 Mt – just 13% of the target”

The IEA’s net zero scenario was a big deal, when they first gave it a go in 2021 after pressure from climate groups. It was the first scenario they published which started with a temperature goal, and then solved backwards. But to solve that equation, they have consistently relied on a volume of CCS deployment that doesn’t seem to be matched by real-world manifestation – and models need to change to reflect the persistent reality.

To continue the comparison with wind and solar, these two technologies exhibit the exact opposite effect: the IEA’s scenarios have historically underestimated the deployment of the technologies (across all their scenarios). The two graphics below4 compare the 2014 ‘World Energy Outlook’ scenarios, and their assumptions on wind and solar power generation, to the 2024 edition’s projections, overlaid with what both actually generated each year:

Again, it’s worth defending the IEA here. They are keenly aware of how the technology is being proffered particularly by the fossil fuel industry in an absurd, over-stated context. They said as much in their 2023 ‘oil and gas transitions’ report, where they point out CCS in a scenario with no change to the oil and gas produced would require “26 000 terawatt hours of electricity generation to operate in 2050, which is more than global electricity demand in 2022”, and would also require “over USD 3.5 trillion in annual investments all the way from today through to mid-century, which is an amount equal to the entire industry’s annual average revenue in recent years”

The IEA have also been at pains to point out they are not the worst offender when it comes to leaning on CCS to model climate ambition: showing that their reliance on CCS in net zero models is a lot lower than the IPCC’s reliance on CCS. They’re not wrong.

To give you an idea – here are 146 1.5c-aligned IPCC scenario assumptions5 showing the total amount captured by CCS each year, compared to the actual installed capacity from the GCCSi database:

A recent study by Tsimafei Kazlou, Aleh Cherp & Jessica Jewell published in Nature showed that if you consider a reasonable but optimistic feasibility of CCS growth, that is still significantly slower than what 90% of IPCC 1.5c mitigation pathways assume (noting that the recent AR6 report does go to some lengths to include some CCS-free scenarios). “We show how realistic assumptions about failure rates, based on the history of CCS and other historical benchmarks, can identify a feasible upper bound of CCS capacity in 2030 (0.37 Gt yr)”. That is, to give you an idea, about 10x smaller than the amount of CCS Equinor assumes in its ‘ambitious’ climate scenario.

The net result of a heavy dose of CCS assumptions in authoritative scenarios, projections and models – one that doesn’t reflect the real-world dynamics – is a significantly increased risk of missed targets, and a false impression of ambition. I have truly lost count of the number of times a fossil fuel company references either the IPCC, or the IEA, when justifying heavy, load-bearing promises on CCS.

Here’s one nice, recent example. This is from ExxonMobil’s latest ‘Global Energy Outlook‘, showing carbon capture growing at three times the rate of wind and solar, from 2022 to 2050. This isn’t Exxon’s own scenario assumption -this is ExxonMobil referencing the IPCC’s ‘below two degrees’ scenarios:

‘See?? Even the climate scientists that you love and trust agree with us that leaning heavily on carbon capture is a totally fine thing to do’. I don’t know if it’s well recognised in the climate modelling community just how widespread stuff like this is, within fossil fuel company climate and sustainability claims.

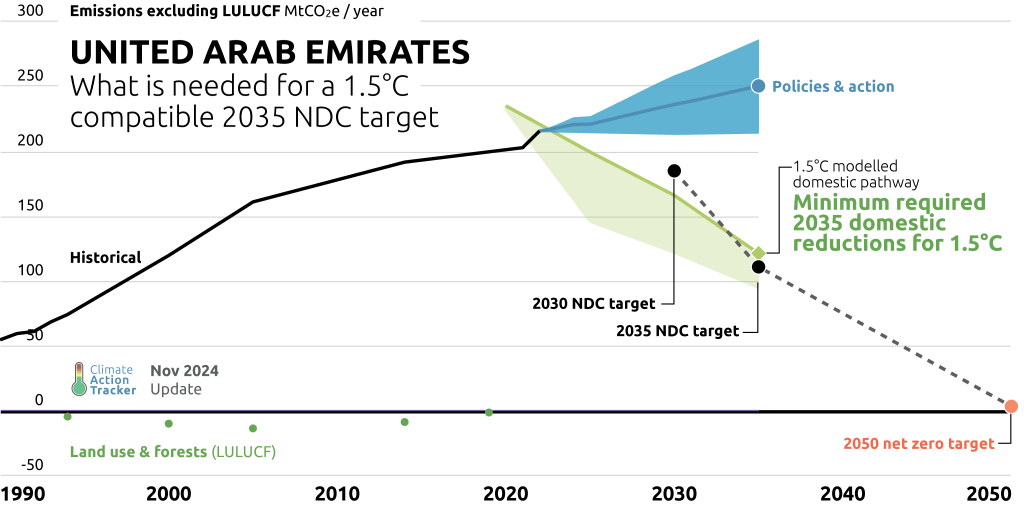

Also consider the UAE’s new 2035 target, announced at COP29, featuring what seems to be quite an ambitious, 1.5c aligned 2035 goal:

The problem, of course, is that the UAE’s 2035 target seems to rely heavily on the assumed deployment of CCS to hit that 2035 level, according to Climate Action Tracker’s analysis. ADNOC, the country’s state-owned fossil company, did a huge announcement last year around a doubling of their CCS targets – except it was a doubling of a miniscule value.

This is part of a trend that I’m calling “predatory ambition” – the tactical setting of ambitious-looking but unattainable climate targets6, and I’ll be digging into it in more detail in a future post.

For now, all you need to look at is the IEA’s useful COP28 pledge tracker, which shows the amount of installed CCS compared to the 2030 target:

There seem to be two non-overlapping worlds here. The world of scenarios, targets and projections: where the CCS revolution is always just around the corner. Optimism of the worst kind; just as immune to evidence as denial. And the world of measurement and performance, where it is exceedingly clear that the single best form of carbon capture is not digging it up in the first place.

CCS is still a fossil fuel industry tool

At COP29, there are 480 CCS lobbyists listed on the official register – an increase from COP28 in Dubai, despite there being significantly fewer overall attendees for this COP.

“If left unchecked, corporate capture — as demonstrated by the volume of fossil fuel lobbyists roaming the corridors and rooms of COP29 — will continue to impede progress towards climate action. It is long past time for the UNFCCC and States to address the obvious conflict of interest of allowing those who are harming the planet to influence the process of saving it,” said CIEL Senior Attorney Erika Lennon. It’s true: CCS is still an engine of climate delay for the fossil fuel industry.

The simplest manifestation of this is when CCS gets used as a rhetorical tool to justify new fossil fuel projects. And it’s extremely likely that the Biden-era IRA incentives for CCS are going to stick around (and possibly be expanded) under Donald Trump, resulting in a worsening of all these problems.

This is all much worse when you realise that the fossil fuel industry- which has been raking in ultra-profits thanks to bloody conflicts and cost-of-living crises – has managed to support this broad greenwashing ecosystem largely using public funds.

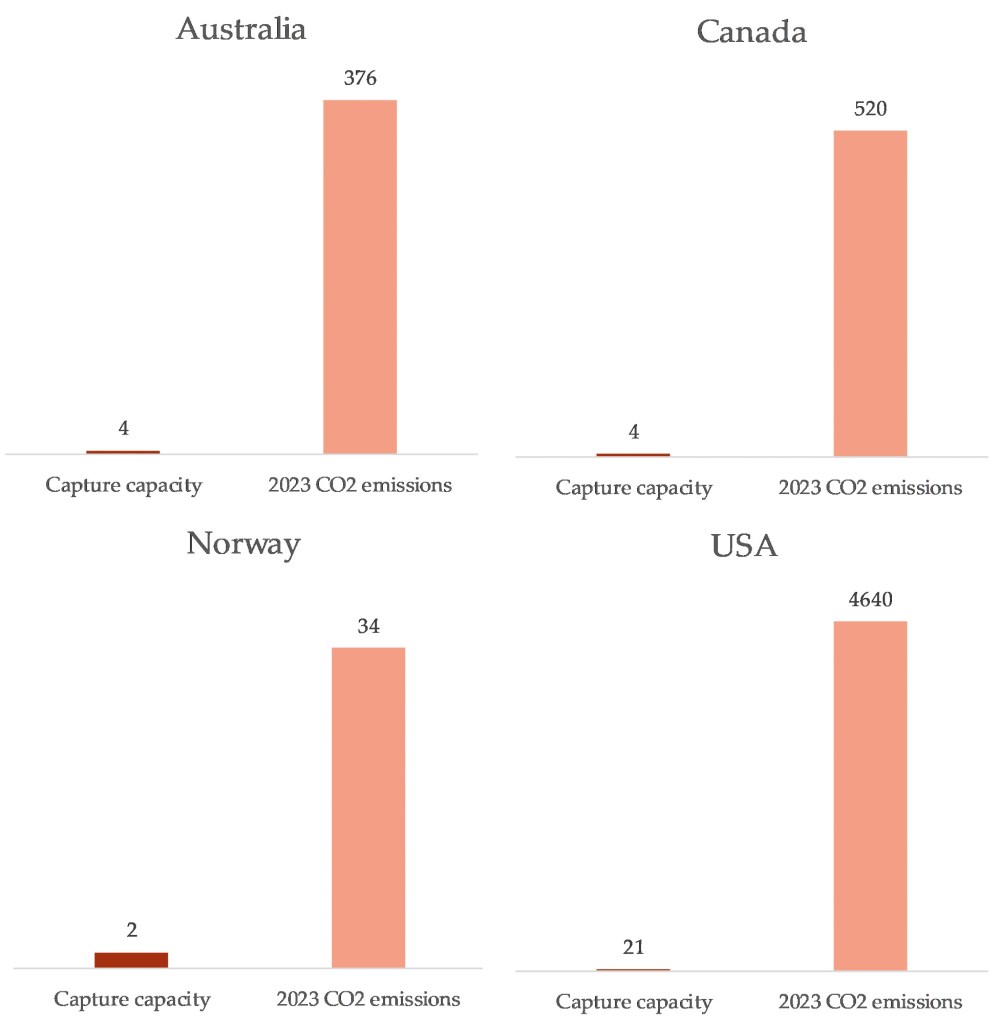

This recent report from Oil Change International puts together the vast sums of public money that have gone towards incentivising CCS – and I’ve added a second graphic showing, for each of the major funders with operational CCS, how the emissions avoided compare to actual emissions for each country:

A line I’ve heard a lot – often in response to my CCS posts – is that CCS is ‘needed’ for heavy industry and ‘hard to abate’ sectors. Calm your farm: CCS for fossil delay is a thing of the past.

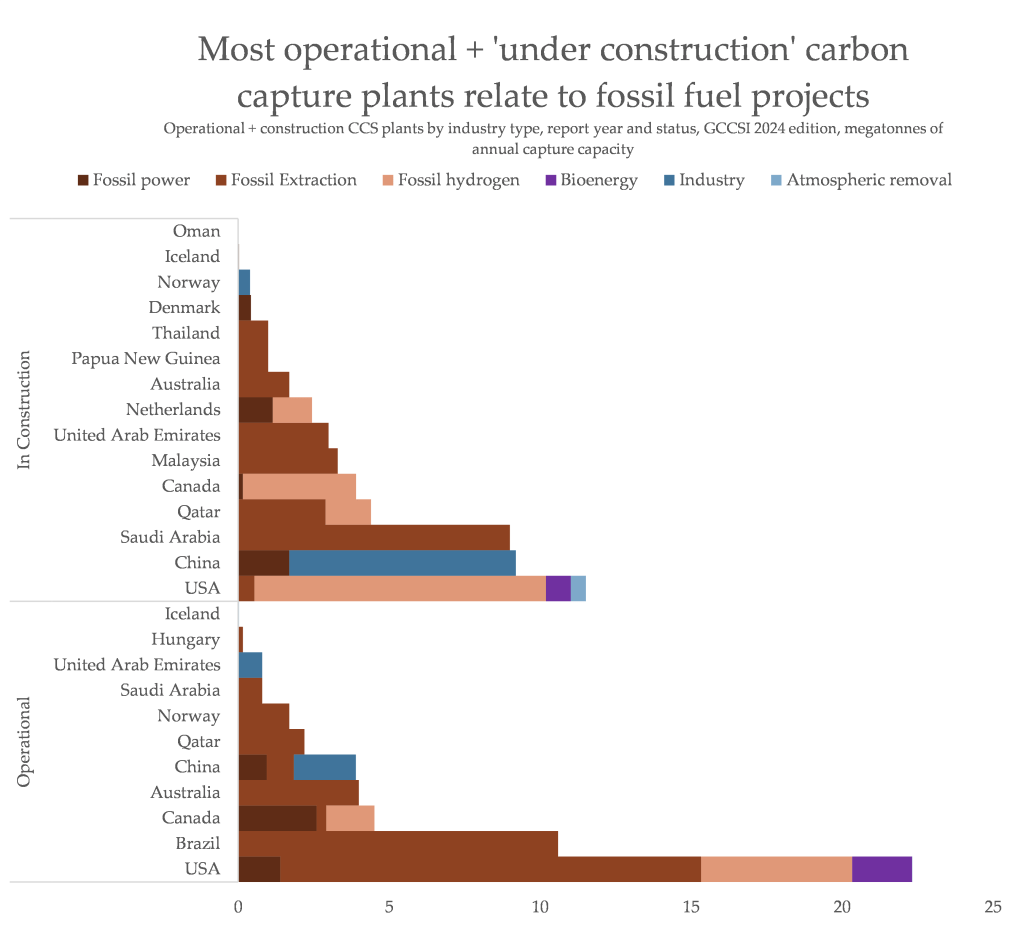

But there still hasn’t been a shift where CCS stops being a tool for fossil industry expansion and starts being a tool for decarbonising unavoidable heavy industry and manufacturing.

The rise in operational CCS between 2023 and 2024 comes largely from the reactivation of the CCS attachment to the Petra Nova coal plant: previously, the captured carbon was being used to dislodge more oil, and the rising oil price means it’s now profitable again to run that CCS. Very grim.

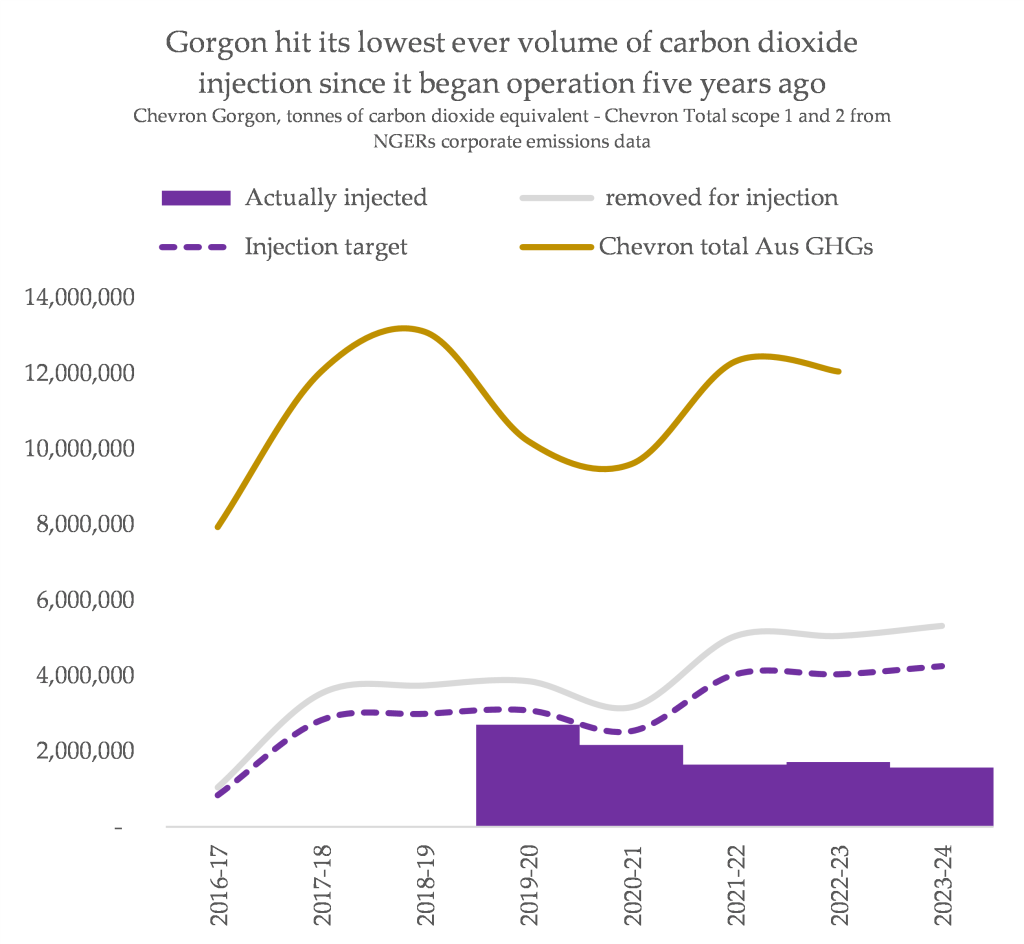

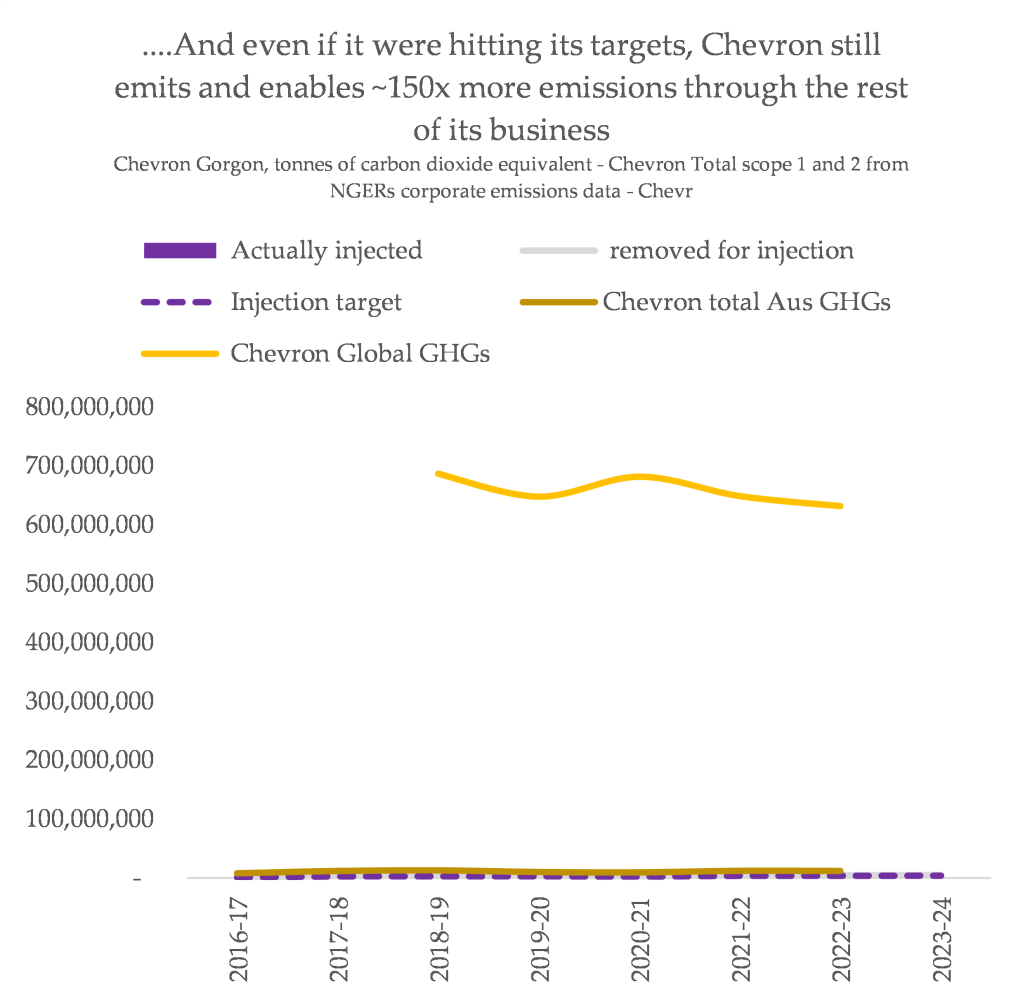

Something worth noting too for the operational projects is that this data is only showing the capacity of CCS projects; not what actually gets captured. Just a few days ago, Chevron very quietly released the latest ‘environmental performance report‘ for its expensive and heavily publicly funded Gorgon7 CCS project in Western Australia, which is used to greenwash one of Australia’s largest fossil fuel extraction sites. It shows the facility injected the lowest amount since it began operation, and had the worst shortfall relative to its injection target as well:

Chevron has to remove carbon dioxide from the stream of gas it’s pulling from underground, because it has to separate it from the methane it wants to sell. But of the 5.3 megatonnes it removed to be injected underground in 2023-24, only 1.6 actually ended up underground. The rest? Vented into the atmosphere. Since it began operation seven years ago, two thirds of all of the carbon dioxide ‘removed for injection’ has been pumped into the planet’s atmosphere. Gorgon, the CCS “success story“.

It’s cool though: they buy carbon offsets for everything they don’t store underground. Yes, those carbon offsets.

Globally, almost all of the increase in ‘construction’ projects between 2023 and 2024 come from fossil gas CCS projects in Saudi Arabia and Qatar. The enablement of fossil fuels – burning it for power, digging it up from the ground or converting it into hydrogen – remains the core function of CCS, with a few projects relating mostly to bioenergy (itself highly controversial and damaging), and in early development, to heavy industry.

The fossil fuel related CCS projects are largely concentrated in the US; an indication of how significant the ongoing effects of the IRA’s CCS subsidies are going to be:

It is a dangerous thing, to propose a climate solution that promises to preserve the status quo and prolong the fossil fuel industry. These can be on-paper ‘neutralisation’, like purchasing a carbon offset to claim climate action. They can be ‘natural’, like overstating the capability for trees and grasses to breezily re-absorb the obscene volumes of carbon dioxide we are transferring into the air, and setting reassuring but dangerously weak climate targets based on that assumption.

Or they can be technological, like the decades-old idea that fossil power stations and extraction projects can continue unbothered if they just slap on some CCS.

There is no other climate technology quite like this – nothing that has sustained such high levels of public funding, credulous trust among professionals and deep presence in climate scenarios, paired with such a persistent failure rate that began well before I was born. If we don’t break the spell now, the danger of CCS complacency only gets worse.

- This is percentage change, so remember that solar is starting from a very low base ↩︎

- Honestly I just want to say how proud I am of myself for this one, look at it, it’s BEAUTIFUL ↩︎

- Note that Shell very quietly dropped its own CCS target earlier this year ↩︎

- I’m going to be doing a bit more from the IEA’s WEO, including compiling many more years. It’s actually not clear to me whether this ‘underestimation’ phenomenon is still happening, but it’s tricky. Depending on how you extrapolate the years between now and 2030 (a straight line, or a growth curve), they can look either on track with the most ambitious scenarios, or worse than the worst-case scenarios……. ↩︎

- I filtered out any scenarios that didn’t feature a number for any of 2025, 2030 and 2035 – weird number of blanks in the data? Also: there are a few scenarios in this bunch that actually avoid assuming heavy reliance on CCS, but there are plenty that don’t. ↩︎

- Interestingly enough, Shell quietly dropped its 2030 CCS target without anyone (except me, lol) noticing – either they don’t feel the need to greenwash anymore, or they don’t want to be held to account for their promises against new anti-greenwashing regulations. ↩︎

- Incredibly, Royce Kurmelovs also just reported that the West Australian government is increasing its funding for carbon capture and storage. “The announcement was welcomed by the Australian Energy Producers (AEP), the country’s longest running oil and gas industry association, formerly known as the Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration Association”. ↩︎

Hi Ketan, Really appreciated your post on renewables riding roughshod over biodiversity and people. I had not realised that onshore wind has done its dash in Norway. Same is happening here in Tasmania. Here is a piece I wrote for ARENA magazine about the proposed Robbins Island windfarm. A worse site for a windfarm you would be hard pressed to find. Tasmania already has nearly 100% renewables because of Hydro and no discernible increase in demand but is now intent on building 200% for export via cable to mainland Aust. Problem is that the cost of the cable means that the energy produced won’t compete with cheaper mainland based renewables plus mainland based chemical batteries have outcompeted Hydro storage for firming. It is a neoliberal ‘jobs and growth’ strategy of using energy generation as an economic driver and destroying the environment at the same time when there is no demand. All mainland states have now 100% renewable targets and Victoria doesn’t include one electron from Tas in its plan to get there. Cheers Christine

Summoning Up the Furies Page 22.

>

LikeLike

Thanks for your work Ketan.

Fascinating and infuriating, though predictable.

LikeLike