Why no one is asking questions about Spain’s mysterious missing nukes

Large scale blackouts happen all the time, but when they happen on a grid with a decent volume of wind and solar, a disinformation machines spins up within minutes to lay the blame solely, loudly and repeatedly on renewable energy. See: South Australia, 2016. UK, 2019. California, 2020. Texas, 2021. It’s a thing.

It was no different after a major blackout hit Spain last week. A narrative pushed by a few business columnists, nuclear power advocates, centre-right ecomodernists, very-right fossil fuel advocates and climate delay practitioners contributed to a widespread assumption that the blackout occurred thanks solely to Spain’s investments in wind and solar.

There has been no official detail on the sequence of events that led to the blackout, besides a few vague details on disconnected generation. That hasn’t sapped the vibrating excitement the people above have shown in aggressively pre-blaming the blackout on renewables. The debate centres around the inherent characteristics of different types of generation technologies: traditional generators use large spinning rotors that have, in the past, helped secure systems through the inertia of that spinning mass. Newer technologies like wind and solar operate on a different paradigm, and deeper structural changes are needed in systems with high volumes of both to ensure grid reliability. There’s a thick layer of politics and identity on top of that, along with direct financial interests and political corruption going in many different directions.

This post is not about spinning rotors, nor is it about what ’caused’ the Iberian blackout. Until we know more, I want to interrogate a narrative that’s sprung up in the wake of the incident: that nuclear power is the cure.

Spain is a global leader in the deployment of both solar and wind power. It’s #6 on the global country ranking for wind/solar proportion (43%), for 2024. But Spain is also one of 30 countries in the world with substantial nuclear power (20th on that list). It has a 20% share of nuclear in 2024: higher than the US, UK, Russia, Canada or China.

The widespread claim that Spain could’ve prevented the blackout with nuclear power seems to weirdly ignore the fact that Spain already has nuclear power – more than most other countries in the world. So….what happened?

The confused narrative

The government plans (very controversially) to phase nuclear out by 2035 – a decision that seems to have been wavering in the weeks before the blackout and that has also provoked the ire of communities that rely on those plants for jobs and local economic benefits.

That future plan somehow transmogrified into the broad belief nuclear had already phased out. You can find thousands of examples of this, but here’s a particularly badly phrased one:

More absurdly, Bloomberg’s columnist Merryn Somerset Webb called for “speed building” nuclear power in response to the crisis.

“Perhaps if we’d embraced nuclear properly 30 years ago, we wouldn’t need to worry about emissions— or for that matter grid security. Which would be nice. Relaxing even” (Merryn ends the piece with a list of investment suggestions for uranium stocks).

Got some good news for ya, Merryn. Spain did in fact embrace nuclear properly thirty years ago, and that capacity has remained steady ever since, according to the latest update from the World Nuclear Association:

Spain has plenty of nuclear power (in addition to hydro, gas and a small amount of coal, too). Nuclear power generation has barely budged over the past two decades, in terms of how much it generates as a proportion of the country’s total. Whatever Spain’s planning to do in the future, at the time of incident on April 28th, it had as many nuclear plants as it did when I was five years old, and in recent years, those plants have generated at a steady pace.

So what happened in April, 2025?

The shutdown

At the time of incident, Spanish nuclear power was generating 3,384 megawatts of a potential 7,123 megawatts. As a percentage of total possible nuclear output (‘capacity factor’), it was 47.5% (which isn’t all that far from offshore wind’s average capacity factor of about 40%). That is unusual for nuclear power, which almost always operates at a far higher capacity factor.

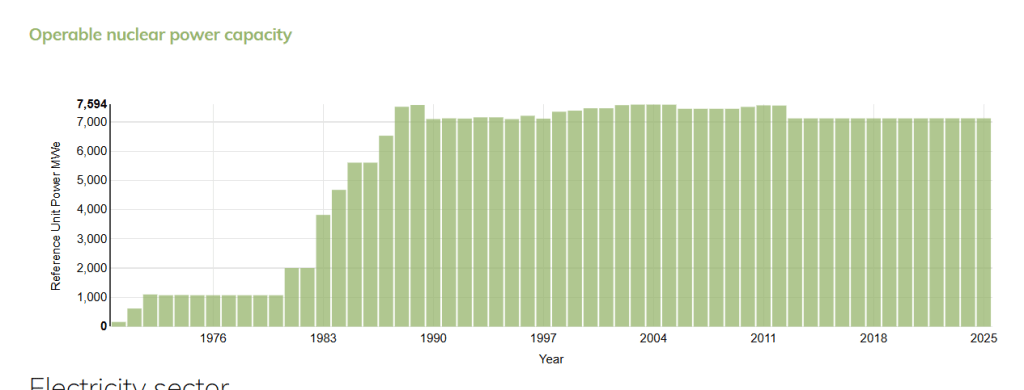

That is strange. First, I checked some recent data – you can see that the week preceding the blackout was one that saw high (but not unusually high) wind/solar output, along with weirdly low nuclear output:

To give you an idea of how weird nuclear power output was, here’s the country’s daily nuclear generation from the start of 2023 to April 27th, the day before the blackout. You can see the dip down low on the far right of the image:

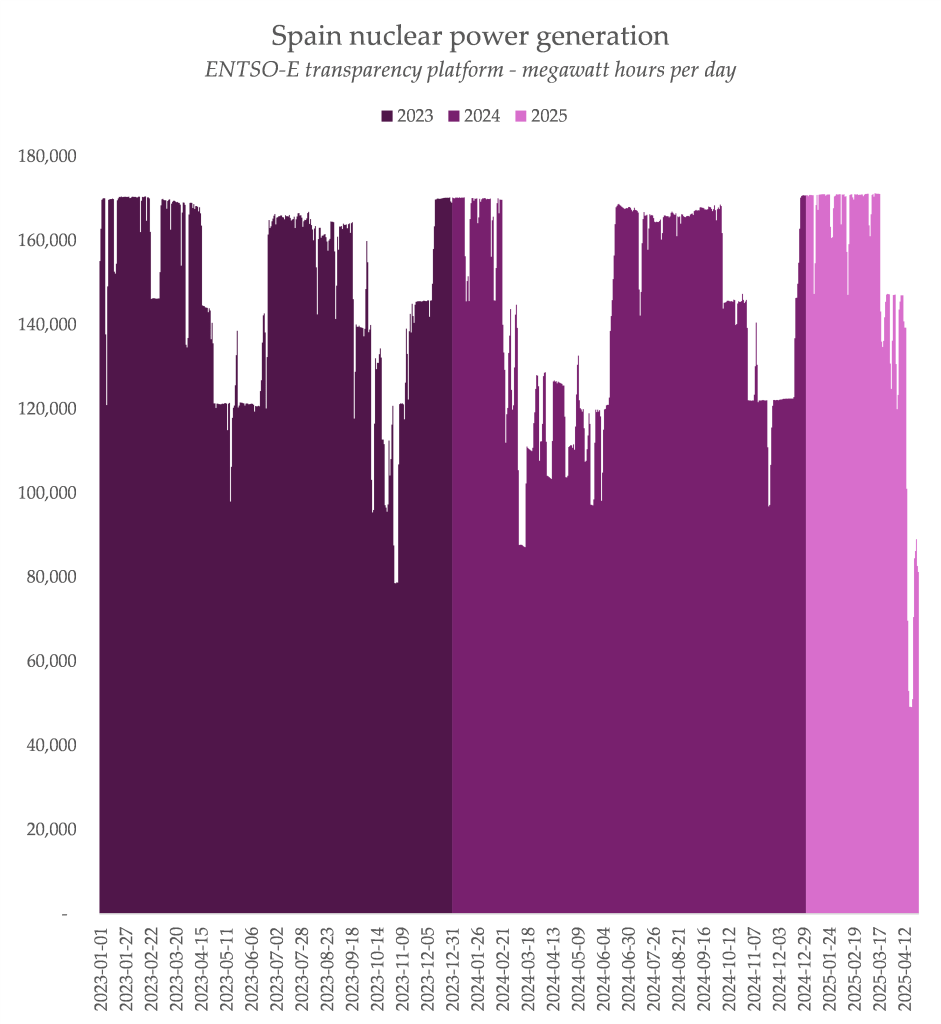

Or, to demonstrate it another way – you can compare April’s nuclear power generation between 2025 and 2024:

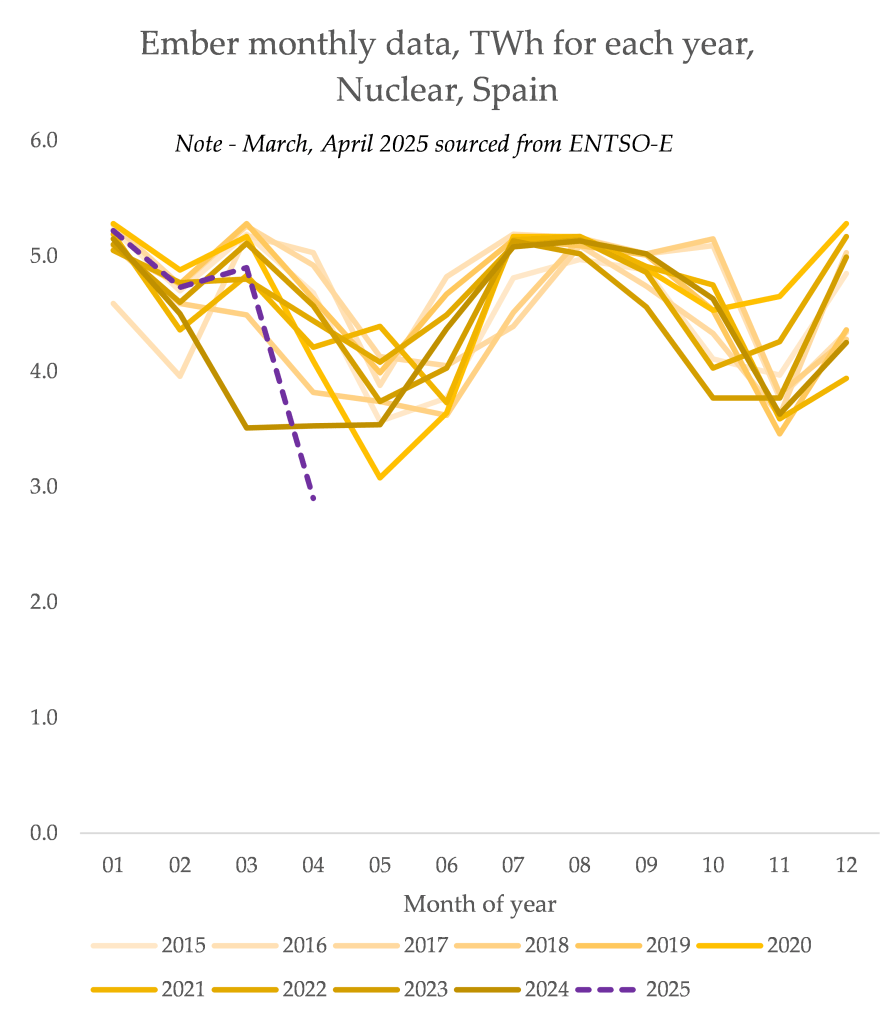

Maybe this happens regularly outside of April, and we’re looking too narrowly? No – it doesn’t. This reduction in nuclear power is highly unusual for Spain. Even if you only look before the blackout, April 2025 was inarguably destined1 for the lowest nuclear power generation since at least 2015, according to Ember’s data:

This is significant, right? Nuclear power was abnormally low in the weeks preceding and on the day of the blackout. So, I wanted to find out why.

The weird justifications for Spain’s nuclear shutdown

The most direct reference I can find is this, from a Reuters article, referencing the two units of the Almaraz nuclear power station (only 2 gigawatts of the total missing 3.7 at the time of the blackout):

“[A week after a debate on the future on nuclear in early April], Almaraz temporarily shut down the two units citing abundant wind energy supply as making operations uneconomic. One unit was still offline on Monday [the 28th, the day of the blackout]”

Another sources cites this reason:

“….the economic unviability caused by the high taxation of nuclear plants, the low electrical demand in recent days, and the high generation of renewables”

It is absolutely zero surprise here that the shutdown of nuclear power is being blamed on renewable energy. Nuclear advocates have a pathological decades-long history of blaming every single one of their woes on the dirty greenies, and this seems no different. Bloomberg recently ran this line, but it was vigorously denied by France.

Almaraz 1 and 2 comprise two of Spain’s seven gigawatts of nuclear: both the oldest plants, connected to the grid in 1981 and 1983 respectively. That means they are both first on the chopping block for Spain’s nuclear phase-out: “The planned closure of two nuclear reactors at southwestern Spain’s Almaraz plant, starting in 2027, will increase the risks of blackouts, European power lobby ENTSO-E said in April”.

We can do a simple sense check on both of those claims: first, that wind power output was freakishly high in Spain, and also whether the price of power in April has been abnormally low. Nuclear power has never shut down to this depth in Spain – so these circumstances must be similarly abnormal, to justify the shutdowns, right?

Well – not really. April was not a particularly high month for wind power output in Spain. In fact, the days preceding and the day of the blackout were kinda low for wind power:

This is…..pretty significant. For at least two of the missing gigawatts of capacity, the rationalisation offered, blaming high wind output, seems to be questionable.

Maybe they meant wind and solar together? It is, unsurprisingly, the same story: wind and solar’s combined contribution in April 2025 was high but absolutely within expectations and recent history:

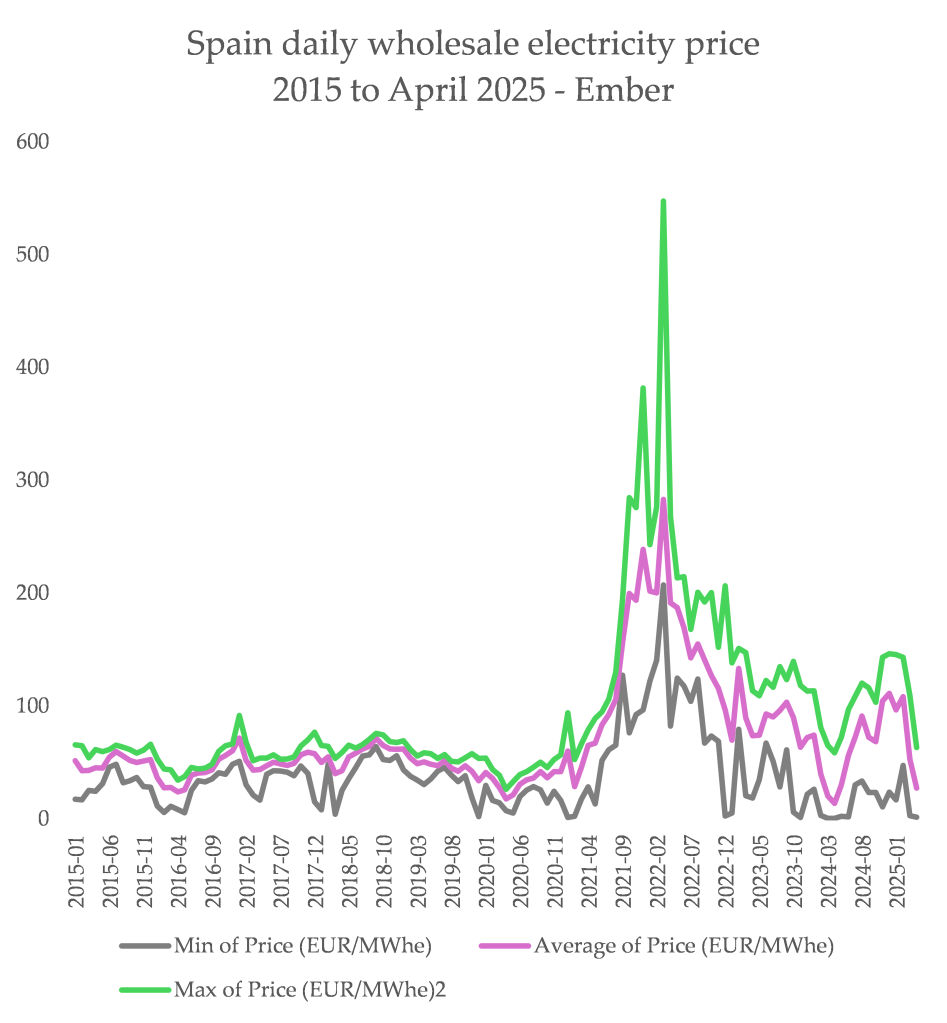

What about the claim of the ‘economics’ of running nuclear in a high VRE grid? It is true that, generally, more wind and solar depresses wholesale power prices. It often results in smaller profits for every power generator (including wind and solar, in a self-destructive way).

While April’s wholesale electricity price was low relative to recent months, the post-energy-crisis earning per megawatt hour have been massive, and 2025’s April prices were on average higher than 2024, 2020 and 2016. Low wholesale prices have happened before in Spain and don’t seemed to have triggered the sudden obliteration of more than half the country’s nuclear capacity.

There could be an element of truth to this, given the prominence of negative prices in April 2025 – but this was a Europe-wide phenomenon, and I haven’t seen reports of nuclear plants in other European countries responding by simply shutting down entirely and de-rating output to a fraction of capacity. It is also worth noting that wholesale prices were driven negative in Spain partly due to hydro power plants generating in the middle of the day rather than just wind and solar output.2

Spanish wholesale power prices were unusually high in the months leading up to nuclear’s shutdown in Spain. They were relatively low in the weeks prior, but not abnormally so. What was different about mid-April 2025, that justified the unprecedented, partly-intentional, partly-mysterious shutdown of half of Spain’s nuclear fleet?

Make this make sense

Looking deep into this data flips the script. The story told in media is that Spain was suffering from ‘too much solar’. Who has been asking why half of Spain’s nuclear fleet was taken offline at the time of the grid instability?

We can say with confidence that on April 28th, Spain was not seeing an abnormal volume of wind or solar generation relative to the past few years. When the country’s nuclear plants were shut down, wholesale prices were low, but again not abnormally or unusually so (and not relative to other similarly nuclear-enabled countries).

The only truly unusual profile that emerges is nuclear power seemingly being downrated to its lowest level of generation for at least ten years (if not much longer), in the weeks preceding the blackout. The only verifiable information for some of this downrating relates to a politically red-hot nuclear facility currently in the midst of an intense debate about its future, which seems to have intentionally shutdown with at least questionable justifications around opaque economics.

The muddled story of nuclear power as a saviour for grids, which we should “speed build” immediately, is questionable. If we accept that as true, the implications are massive: even when nuclear power is installed and present, it can’t be relied upon to supply energy or stability unless the cost of power is above a certain level – erasing all of the benefits of capturing the free fuel of sun and wind. Nuclear shutting down if power is cheap means that as electricity gets cheaper for consumers, nuclear becomes significantly more unreliable.

If we accept the rationalisations offered by nuclear power operators, it screams of a broken incentive system around grid stability that seems to have had extremely significant consequences for Spain and Portugal. In this world, nuclear power is fundamentally incompatible with a world in which we seize on free liquid, atmospheric and solar resources to supply electrical energy. Nuclear is only the hero of the power grid when the price is right3. It raises the simple question: surely there’s a cheaper, more reliable way of integrating wind and solar? One that doesn’t demand a persistently high power price?

If we’re a little more cynical, I think there’s at least a chance politics played into these oddly-rationalised decisions, considering how significant the blackout will be when it comes to decisions around the future of nuclear power in Spain. Strategically witholding capacity as a tool for creating the political, media and social conditions for self-preservation isn’t unprecedented. Without suggesting at all this is what has happened here, it’s worth revisiting the Enron scandal, in which power traders withheld capacity and caused major rolling blackouts for profit. All this comparison means is that some basic questions should be asked here – but they’re not.

Which brings me to something important: why the broader energy media has failed – really, really badly – to interrogate the behaviour of nuclear on Spain’s grid. Here are some questions I think should be asked:

- Can the operators of the Almaraz nuclear power plant provide justifications for not providing electrical energy to the grid in any detail beyond vague claims of ‘economic’ decision making?

- How expensive does electricity need to be for “reliable” generators to actually provide reliability? Do they publish this anywhere?

- Nuclear power plummeted to a minimum of ~2 gigawatts on the 17th of April, meaning many other plants beyond Almaraz were deactivated to a collectively unprecedented level, and Spanish nuclear had a capacity factor of 29%. Which plants? Why? Were these outages, or intentional shutdowns like Almaraz? Were they planned?

- Was this decision process known to Spain’s grid operator? Are they factoring in nuclear power’s declared inability to generate electricity when power is cheap into their models around system strength and system security – and what alternatives exist?

- What is the near-term outlook for Spain’s nuclear power plants? Given they’ve now operated far outside their normal bounds, how much can they be relied upon to provide energy or system strength?

Other points…

It is striking that on the day of the blackout, April 28th, solar power output was high, but not abnormally high4. It was at a share of 60% when the blackout occurred – there are hundreds of intervals, mostly in 2024, which saw a higher share of solar power among all generation types in Spain. While June hasn’t come around yet, 2024 still beats 2025 in terms of record-high solar intervals:

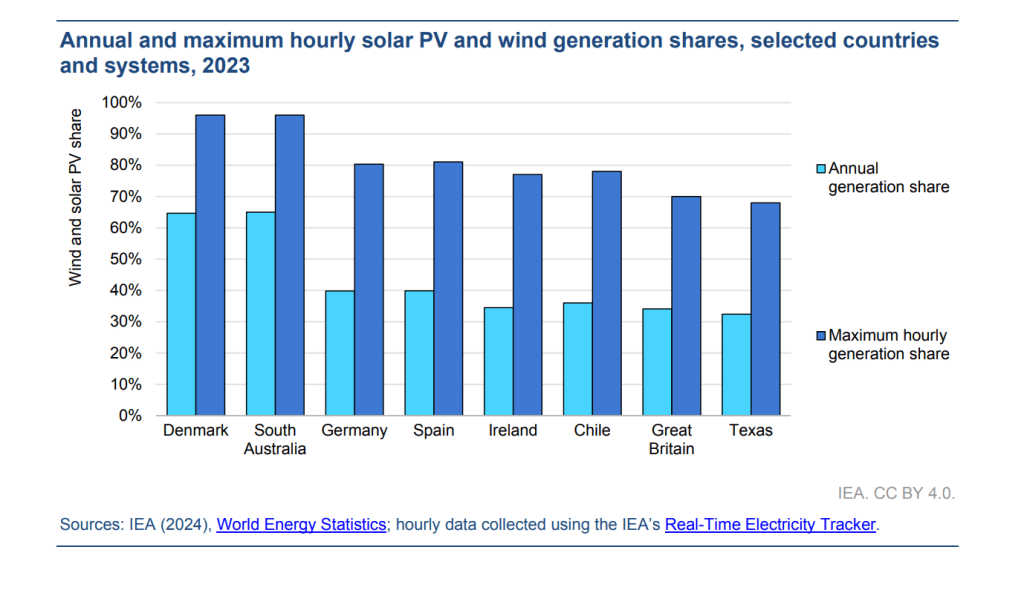

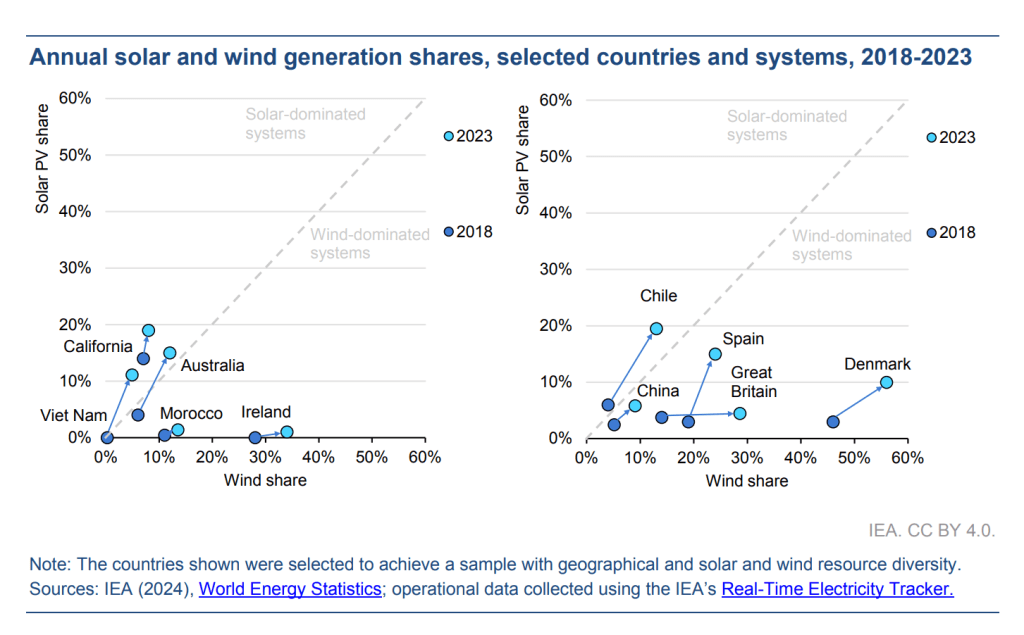

It is also worth noting that in the same way wind and solar generation were not abnormally high on April 28th, the Iberian Peninsula is not abnormal when it comes to high shares of variable renewable energy. This September 2024 IEA report lays out, very clearly, that other regions like the UK, Germany, Denmark, Chile, Ireland, Australia, Kyushu (Japan), Texas and California all manage varying levels of wind and solar, with varying degrees of interconnection into other regions – each with their own suite of challenges, too.

The entire report is excellent – and a demonstration that the complex challenges of grid integration were being discussed, honestly and openly, far before anything happened to Spain’s grid.

- Outside of COVID19, the lowest month of nuclear generation in Spain since 2015 was 3.46 GWh. By April 27th, cumulative nuclear gen in Spain was 2.7 TWh. To beat the next lowest month, it should’ve generated 0.76 GWh over three days (28th to 30th), or 0.25 GWh per day. The most it has ever generated on a single day is 0.17 TWh. So – before the blackout, Spain was destined to have its lowest ever month of nuclear power output ever – for sure. ↩︎

- They have too much water and need to use it to generate power, in short. Read this article for a good explanation ↩︎

- I should have mentioned this earlier, but Brett Christopher’s book, ‘The price is wrong‘, is a really good exploration of what cheap power actually means for privatised, profit driven markets, including the negative consequences for renewable energy operated for profit. The deeper issue here is that greedy gouging by corporations works best with large, big thermal generators and isn’t particularly compatible with smaller, distributed energy resources running off passive, non-extractive fuels. ↩︎

- There were a few articles about solar reaching ‘100%’ of Spain’s power in the weeks preceding: this is share of total demand so it differs materially from the data I’m using, which is share of total generation at the given moment. I don’t have interconnector flows or good demand figures, and ENTSO-E doesn’t seperate rooftop PV, utility scale PV or solar thermal, so it’s tough to do this properly. ↩︎

@ketanjoshi.co a very cheap shot. seriously, blaming nuclear for not stepping in during a network failure. your argument goes for renewables as well. honestly, this is really disappointing from you.

LikeLike

Remote Reply

Original Comment URL

Your Profile

@pavsmith @ketanjoshi.co the article does not suggest that nuclear didn’t step in but that nuclear stepped out.

LikeLike

Remote Reply

Original Comment URL

Your Profile

@peterbrown @ketanjoshi.co the whole grid stepped out. it has since become a cheap shot against nuclear power. the same argument here goes against renewables, coal, gas, whatever… but, never miss a chance to push a dogmatic ideology, i guess.

me? i don't really care. i do though look at long term agricultural scenarios for a living. they're very ugly. we should be doing everything we can to decarbonise power and energy. now.

instead we're having arguments about cost, construction time, decommissioning time, waste management…

…all the while we're burning fossils and storing that waste in the atmosphere and oceans, where apparently it can do no harm.

what is the outcome people are looking for by dogmatically opposing nuclear?

LikeLike

@pavsmith @ketanjoshi.co so you’re pro nuclear. Don’t be ashamed. There are still a few of you around especially in the upper ranks of government and industry.

But many countries are already 100% renewable and the cost trajectory for wind, solar and battery storage keeps plummeting lower and lower whereas nuclear stubbornly refuses to reduce. It is in its death throes, unable to compete with the new boys on the block.

LikeLike

@peterbrown @ketanjoshi.co no. i just happen to see what is going on in the world. do you know anything about phosphate poisoning? and its effects on crop yields?

so what? well, it becomes a problem as increasing heat moves growing zones around and fertiliser is increasingly needed to maintain crop yields. crop rotation becomes impossible. (has become impossible, frankly)

how about i try "i cannot believe you are not in a mad panic trying to get every piece of carbon producing power out of the grid immediately". you think you have the luxury to oppose nuclear for time, money, whatever? do you know the consequences of not doing so?

"many countries" – name a single one. Albania still has standby gas kept hot. Norway – also 98% – has nuclear. both countries have abundant hydro. that's impossible to replicate most anywhere else.

LikeLike

@peterbrown @ketanjoshi.co if my commentary on phosphate is confusing in a fuel context. you're among a huge number of friends.

LikeLike

@pavsmith @ketanjoshi.co not confusing just irrelevant. Phosphate based agriculture only impoverishes the soil and without soil we are all dead.

There are lots of ways of poisoning the planet.

Nuclear waste is one.

Chemical agriculture is another.

Fossil fuels is another.

Perhaps instead of banging on about nuclear energy you could consider the merits of agrivoltaic systems – they are a win-win for everybody.

LikeLike

@pavsmith @peterbrown @ketanjoshi.co Isn't Phosphate in short supply, and likely to become a limiting factor?

The crisis at the beginning of last century was Nitrogen, and Haber solved that, we can expect a whole series of surfeit, depletion, and misplacement crises. Whether they are great filters I don't know.

LikeLike

@midgephoto @peterbrown @ketanjoshi.co eventually it cases serious soil degradation and consequent drops in yield.

same goes for herbicide and pesticide use, but even there the industry is doing some very interesting things: https://smallrobotco.com/

damnably clever.

LikeLike

@midgephoto @peterbrown @ketanjoshi.co however, monocropping and "sweating the soil" are causing havoc.

and then there was the "agricultural miracle" in Saudi, because they had all this water under their feet! thankfully they have apparently stopped this dumbarsed idea! https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arabian_Aquifer_System

LikeLike

@pavsmith @peterbrown @ketanjoshi.co

Slightly puzzled. Around here there is visible* crop rotation.

But is monocropping because there is a crisis in Phosphate, or the cause of a crisis in Phosphate, two of your near-adjacent postings seem to indicate each.

* so if I have an idea on how to better do a picture I took one year, I can't do it against the same field – lighting etc – the following year, but have to wait two more years.

LikeLike

@pavsmith @peterbrown @ketanjoshi.co

I expect straining Phosphate out of the run-off water and drainage would be hard work, but perhaps worthwhile, perhaps we could use temporarily surplus electricity to drive a process to do it some of the time, or at varying rates.

LikeLike

@pavsmith @peterbrown @ketanjoshi.co

Clever gadget!

I have a lawn robot, which I like, but I'm disappointed it doesn't do a raster scan across the (patch of grass we call a) lawn, inspecting each plant, deciding if it is a grass blade or one of the permitted species, and either trimming it or pulling it out, Very slowly on low power.

I hope agricultural robots might work similarly.

Rotating blades and spraying stuff are disappointing.

Machine learning might even be useful.

LikeLike

@midgephoto @peterbrown @ketanjoshi.co those ones use visual modelling/recognition to determine what/how it will treat the pest. the microdosing of herb and pesticides. it also uses weather conditions and forecasting, rain mostly, to determine "should i even bother to treat this weed now?". if not then it waggles a mechanical finger at it, and comes back later when the conditions are more suitable. damnably clever.

LikeLike

@peterbrown @pavsmith @ketanjoshi.co

I'm not aware of anywhere that is 100% renewable.

I know Portugal hit that for a period of days, various places require no combustion power for parts of days or periods of days.

I quite like the idea of a gas/combined cycle turbine set with a big low pressure holder of hydrogen nearby being topped up by spare electricity when a sink is needed, and lighting up when there's need. Zero carbon, or if it needs to start on methane, at least low C.

LikeLike

@midgephoto @peterbrown @ketanjoshi.co norway is very close using tidal, and most countries that are close are using water in some way because it is reliable and predictable. even there they have some Plan B capability in case of planned or umplanned shutdowns of part of the renewable infrastructure.

Spain/Portugal took that a little further, on the other hand…

LikeLike

@midgephoto @peterbrown @ketanjoshi.co hydrogen i want to see happen if it can be done without breaking something else.

an interesting aside to that, and on a smaller scale, is that the cruise industry is headed that way in a big hurry. already mostly running on LNG, ports are putting hydrogen storage and delivery infrastructure for ships starting to come online in 2026.

they've done this remarkably quietly for an industry typically demonised for pollution.

LikeLike

@pavsmith @midgephoto @ketanjoshi.co increasingly however solar is the future https://www.energyupdate.com.pk/2025/01/30/pakistans-solar-boom-22-gw-imported-in-18-months-10-drop-in-grid-demand/

LikeLike

@pavsmith @peterbrown @ketanjoshi.co

Almost all of Norway's power is hydroelectric – fresh water falling down mountains.

They are I think building a 350kW tidal plant, which I think will be their first.

The Rance Estuary barrage is impressive, in Brittany, and it is surpassed by a South Korean lagoon tidal project, but those are the biggest in the world still.

France has a lot of fission, substantial hydro, solar panels spreading like leaves, and more than a little wind power.

LikeLike

@pavsmith @peterbrown @ketanjoshi.co Turning down the fission generators is odd, conventionally nuclear sells electricity into any market, since the cost of running the plant at low power is closely similar to the cost at full designed power output.

Turning down a set of reactors shortly before a grid crash is something that deserves investigation, and if the owners were playing silly buggers then they should not be allowed to carry on controlling those plants.

LikeLike

@midgephoto @peterbrown @ketanjoshi.co same goes for any form of power generation.

LikeLike

@pavsmith @peterbrown @ketanjoshi.co

The threading is confusing here, but if the idea is that power generation from gas turbine or combined cycle is the same cost at full power as at half power then no, not the same.

The fuel cost for fission is trivial* and fixed** and the fuel cost for combustion is non-trivial, directly related to the electrical output, and variable.

…

* per kWh

** after fuelling

LikeLike

@midgephoto @peterbrown @ketanjoshi.co hence my exasperation at people complaining commissioning a new plant will be "30 years". frankly i'd like to think the human race can exist for several thousand more, and that 30 years is a bit of a blip on that scale. mind you, the way the human race is consuming resources, it has no plan to exist much beyond the next 100.

LikeLike

@pavsmith @peterbrown @ketanjoshi.co

If we need something last year, then it may be fatal.

Even if it would take only 30 years to build, and even if the total of years past and future exceeds that.

We should have started it 32 years ago.

In economics, or perhaps business, it is akin to a liquidity crisis.

In logistics, it is akin to a nail, for want of which a shoe was lost leaving an unserviceable horse, for want of which a battle was lost.

Solar panels scale better than nukes.

LikeLike

@midgephoto @pavsmith @ketanjoshi.co over the last 18 mths Pakistan has installed over 22GW of solar panels. They can be deployed incredibly quickly and there is no downside if they are matched to some kind of storage like batteries or Hydro. https://www.energyupdate.com.pk/2025/01/30/pakistans-solar-boom-22-gw-imported-in-18-months-10-drop-in-grid-demand/

LikeLike

@pavsmith @ketanjoshi.co he doesn't do what you say. What do you do?

LikeLike

Remote Reply

Original Comment URL

Your Profile

Excellent analysis. Thank you for sharing.

LikeLike

@ketanjoshi.co the marginal operating cost of both nuclear and renewables is extremely small, so running a market in energy supply, and relying on instantaneous price signaling in somewhere like Spain where nearly all capacity is in these categories seems an unreliable way of managing it.

Nuclear generates power through steam turbines so should be able to provide spinning reserve, used to stabilise the grid voltage, even if it had been down rated.

In the UK we now have a Capacity Payments mechanism to compensate (in our case CCGT generators) to keep their power plants running and to provide spinning reserve and more general backup for mismatches between supply and demand.

LikeLike

Remote Reply

Original Comment URL

Your Profile

Yes, really interesting point – thought it’s not clear which plants were offline for what reasons, and whether they were still providing frequency control and ancillary services. I guess we’ll find out!

LikeLike

@ketanjoshi.co personally, I’d attribute something like a misconfiguration, chain reaction and human error instead.

Which is basically how almost all grid and nuclear accidents turn out to be.

LikeLike

Remote Reply

Original Comment URL

Your Profile

@ketanjoshi.co

If we have to do this thing with simplistic slogans, the Spanish blackout was caused by too few batteries.

It absolutely makes sense to build batteries to shift solar power to the evening peak. If that had already been done, and the batteries had decently programmed systems, it would have provided the stability needed.

LikeLike

Remote Reply

Original Comment URL

Your Profile

@notsoloud @ketanjoshi.co There are a few other things excess power could be used for, running an Aluminium refinery at low power with wasted capacity; electrolyzing water, might be examples.

LikeLike

Remote Reply

Original Comment URL

Your Profile

@midgephoto

Absolutely. But batteries enough to even out daily variation will displace much more fossil fuel and make more money, they are getting very cheap.

You need to consider also the capital bound in refineries and electrolysers that work only a few hours a day.

@ketanjoshi.co

LikeLike

@notsoloud @ketanjoshi.co

Yes, the economics and energetics are complicated, but with varying power supply we shall need to get more clever.

Al refineries though have to be kept hot all the time, molten, or the cells are wrecked, so the variation is on a baseline, perhaps that might be 50% load, shedding some when the grid is loaded, and increasing when it is over-powereful.

LikeLike

@notsoloud @ketanjoshi.co It is my understanding that batteries supply fast frequency response, but not synchronous inertia. Also, BESS seems very expensive and I don't see batteries contributing for several years. In 2021, Bloomberg New Energy Finance reported they expect BESS to provide 1 terawatt-hour of electricity generation globally by the year 2030 at a cost of $262 billion over this nine year period. The Volta Foundation reported that in 2024, BESS generated 0.363 terawatt-hours globally. In 2024, 30,000 terawatt-hours were consumed globally.

LikeLike

Remote Reply

Original Comment URL

Your Profile

@ketanjoshi.co “it’s worth revisiting the Enron scandal, in which power traders withheld capacity and caused major rolling blackouts for profit.” 🤔

Very good point !

LikeLike

Remote Reply

Original Comment URL

Your Profile

The pricing of electricity and the electricity market is probably the source of a lot of rot at this point.

The EU vision of a free electricity market has clearly shown it wasn’t adapted to the specificity of electricity, which is additionally highly susceptible to the tragedy of the commons. (A stable electric grid is a common).

LikeLike

@ketanjoshi.co

"It is tough to resist actually fact checking a soundbite like this. "

LOL! Too often it is 😉

LikeLike

Remote Reply

Original Comment URL

Your Profile

Nice straw man fallacy by misrepresenting critiques of Spain’s energy policy by pretending that nuclear advocates believe Spain had no nuclear plants at all, when the actual critique centres around the deliberate underutilisation of existing nuclear capacity.

You also conflate economic decisions made by nuclear plant operators with inherent technical unreliability, creating a false dichotomy suggesting that nuclear power either functions perfectly or not at all. A false dilemma.

Lastly, the insinuation of politically motivated capacity withholding, without evidence, is an appeal to conspiracy, deflecting from genuine policy critiques and the documented issue of economic incentives conflicting with grid stability.

LikeLike

you need to close the ‘logical fallacies list’ website

LikeLike