Why dishing out the stats on risk doesn’t change our perception of terror threats

Immigration leads to terrorism. That’s the load-bearing claim underpinning a recent trend in Australian and American political messaging. It seems like a potent line of argument – terror threats are so visceral, and there’s plenty of purchase to be found for anti-immigration sentiment in Australia.

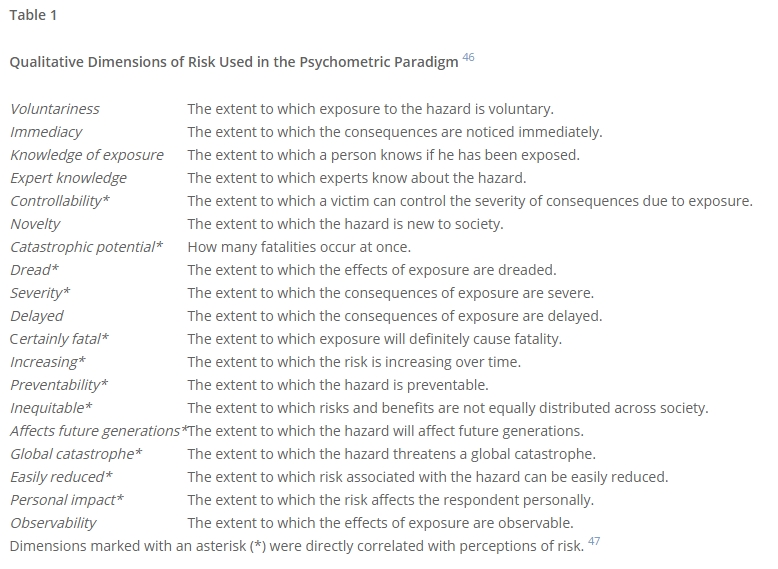

Some of the potency of this feeling comes from the way we perceive risk. There’s a collection of recognisable factors that will skew our gut reactions away from actual, measurable risk and towards ‘perceived risk’. These psychometric factors are good predictors of how we’ll respond to a threat.

Terror attacks are horrific and effective tools for skewing risk perception. They’re catastrophic, severe, unpredictable, fatal, immediate and random. The most recent example targeted children. In addition to the many lives extinguished by these insane acts of murder, the impacts extend well into the hearts and minds of societies.

A recent episode of the ABC’s Q&A illustrated some discussion around actual threat versus perceived threat – as described by Guardian journalist Mona Chalabi and science communicator Lawrence Krauss the night before the Manchester attack:

MONA CHALABI

And actually, the threat of Islamic fundamentalism, if you want to view it in terms of number of dead bodies, which, as awful as it sounds, is the way to kind of make sense of some threat, actually, really, isn’t that present. So, if you take the years from 1975 to 2015, the threat of terrorism in the US…the chance of being killed by a foreign-born terrorist is one in 3.6 million and the chance of being killed by a foreign-born terrorist who was also a refugee is one in 3.6 billion. But all of our perception of threat has been distorted because of the way that risk is presented to us by politicians.

LAWRENCE KRAUSS

Yeah, I agree. I mean, I wrote a piece in The New Yorker saying that and I got castigated. It’s exactly that. We have this view that it’s a huge threat. For most Americans… In almost every country, the likelihood of being killed by a terrorist… The real people who are in danger from a Muslim terrorist are in the Muslim countries.

MONA CHALABI

Yeah!

LAWRENCE KRAUSS

Exactly. You’re more right likely to be killed by a refrigerator, in the United States, falling on you.

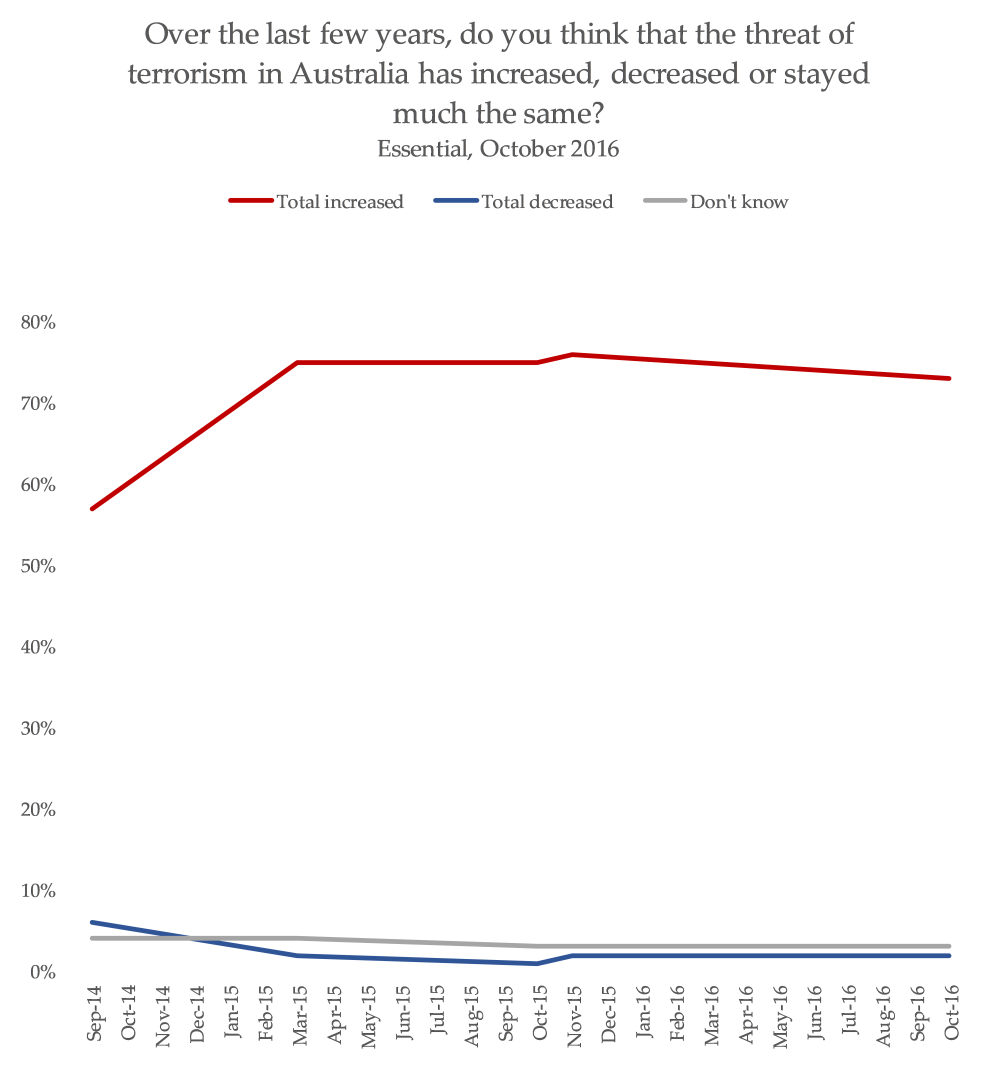

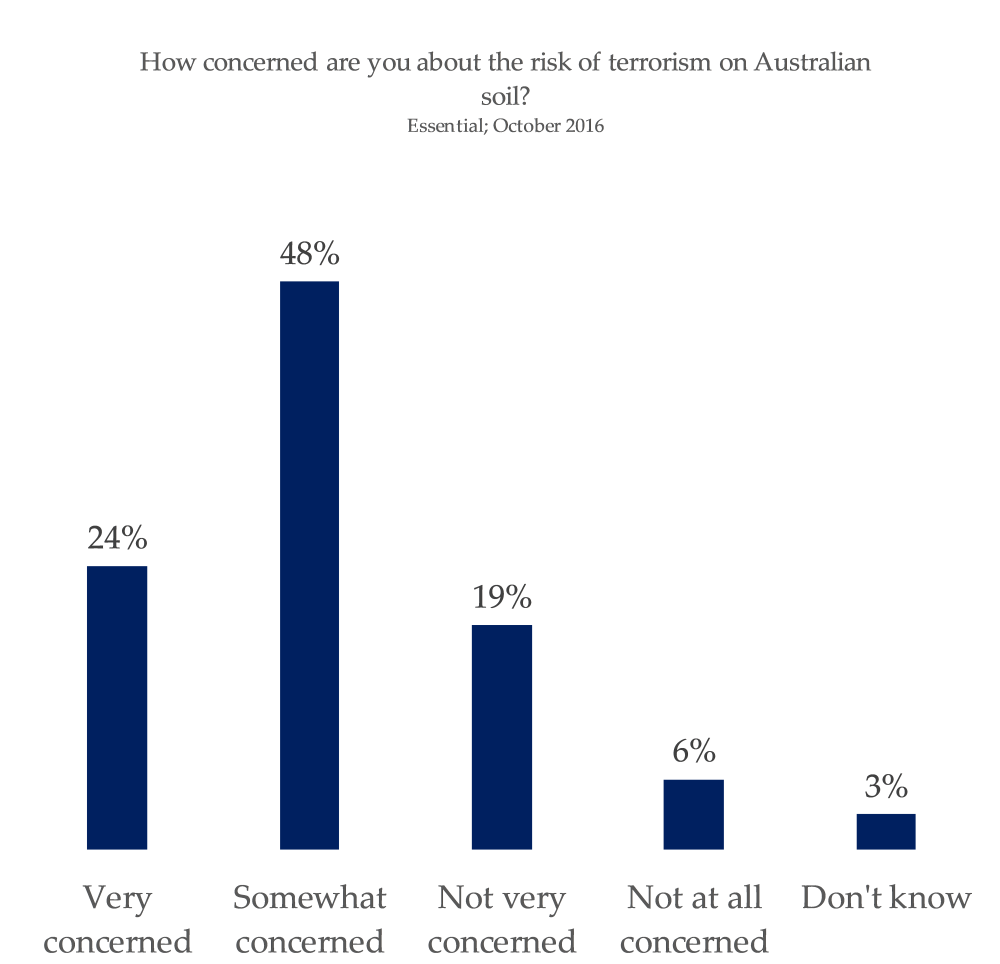

In Australia, the threat of physical injury or death due to terror attacks is similarly low. The perception is far removed from a numerical assessment of this threat – we’re deeply concerned about the risk of terror attacks, and the majority of us perceive this threat as an increasing one:

This isn’t an unusual state of affairs. We also fear shark attacks, plane crashes and war far more than things that are significantly more likely to injure or kill us.

The creation of a gap between actual risk and perceived risk is, perhaps, the primary intention of violent terror attacks. An article published in ‘Homeland Security Affairs’ says,

“Terrorism – more specifically the threat of terrorism – has become a driving cultural and political force. Credible threat is the currency of terrorist organisations”

It seems logical, then, to short-circuit the efforts of terror groups and correct public mis-perception of risk. But is doing so is effective? Do people adjust their concern, after hearing statistics on risk? This 1999 study says not really – but you can change someone’s view on risk if you tailor communication to suit their personal concerns.

This isn’t particularly reassuring. News outlets tend to broadcast content that is very good at widening the gap between perceived risk and actual risk – one study found that exposure to media coverage of the Boston-bombing was related to more acute stress than ‘direct’ exposure (“being at/near the bombings”). How would you reach each of those viewers on an individual level, to tailor a correction?

Broadcast conversation about the mathematics of risk and danger is also met with outrage from conservatives – The Australian‘s Chris Kenny wrote, in response to Q&A’s discussion, that “The ABC was at it again on Monday night, with the guests and host of Q&A once more talking down the threat [of Muslim extremism]”.

Quadrant’s Roger Franklin wrote, with seething anger in response to Q&A’s comments about risk and refrigerators prior to the Manchester attacks, “Life isn’t fair and death less so. If there had been a shred of justice that blast would have detonated in an [ABC] TV studio”.

There’s presumably a reason behind the magnitude of this outrage. To urge an empirical assessment of the risk of terrorism is to chip away at another, parallel political effort – attacks on immigration. There’s been a concerted effort to explicitly call for limitations on immigration as an effort to ‘keep out terrorists’:

Efforts to draw a link between these two issues, however spurious, will be for nought if the people aren’t spending their days fearing for their physical safety. The way we perceive risk is a vital component of this particular sub-component of anti-immigration sentiment.

Average people (me included) tend not to judge risk based on the raw mathematical data examining how likely something is to hurt or kill us. There’s a complex stew of emotion, circumstance and psychology that creates the gap between actual and perceived risk.

Catalysing this feature of humanity is stunningly simple. Reversing this effect is amazingly complex, and it’s unlikely the mere presentation of statistics is doing much more than triggering outrage in conservative elements, for whom a reference to statistical reality is seen as an effort to downplay or deny the threat of terror attacks and remove a line of attack on immigration policy.

After the Manchester attacks, a crowd at a memorial spontaneously broke out into a rendition of ‘Don’t Look Back in Anger’, by Oasis. It was a beautiful moment of resilience, community and unplanned togetherness.

Though a rational assessment of risk is always an important part of decision making, as a community, I wonder if we’re better off short-circuiting the aims of these attacks with utterly inescapable expressions of community strength and resilience, after horrifying incidents of terror. It doesn’t fit the narrative that those seeking to inject terror into our hearts are demanding – that’s an effective and powerful revenge.

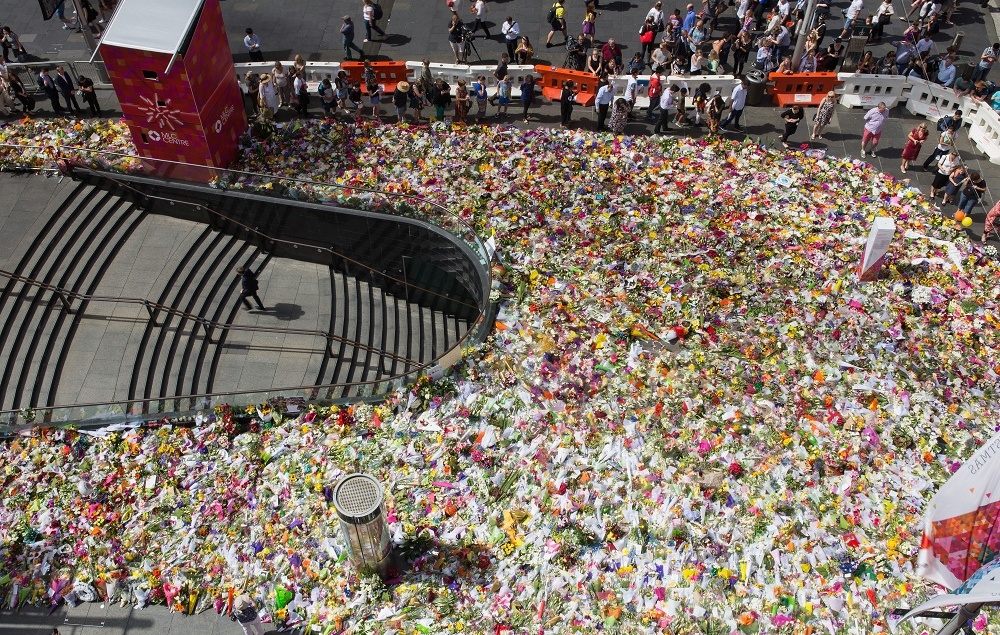

Header photo – a sea of flowers laid in Sydney’s Martin Place after a lengthy hostage crisis.

“We also fear shark attacks, plane crashes and war far less than things that are significantly more…”

Don’t we fear them far more than more mundane deaths?

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Actual Factual Feminism.

LikeLike

Very well written. 🌟

LikeLike