Nature and people shouldn’t be designated losers in the energy transition

It is because climate action is so urgent that we should be careful with how we roll out clean energy.If you are worried about climate impacts, you should worry about how to ensure the growth of wind and solar doesn’t occur in a self-sabotaging and destructive way.

We need speed, yes, but we also need to maintain speed. Sacrificing the latter to achieve the former results in failure.

Sammy Roth, an energy writer with the LA Times who has published some great and valuable coverage of social and environmental issues around renewable energy in California, wrote an opinion piece that lays out a much more strident opinion than his articles.

Headlined “Solving climate change will have side effects. Get over it”, Roth calls for acceptance of the side-effects of a rapid renewable energy build-out and says “we’ll need to stop yelling at each other and start cooperating with people we think are wrong”. In what world does a conflict switch to cooperation when you start by telling them: “GET OVER IT“? That is is not my main gripe with the piece, but jeez, it’s a strange thing to do.

Roth really doesn’t seem to be calling for more dialogue – it is more like a call for environmental advocates and aggrieved communities to talk less. You can see this reflected in the list of compromises to be made – for tolerance of natural destruction, corporate profit and right-wing political power as a pathway to greater clean energy growth:

“To maintain a habitable planet for ourselves and our children and grandchildren, we’ll need to make some compromises. We’ll need to stand by and watch as some pristine ecosystems are razed in the name of renewable energy. We’ll need to learn to live with exorbitantly wealthy investors raking in additional profits at our expense. We’ll need to elect some politicians whose ideas don’t fully line up with our own, because they’re nonetheless our best hope of avoiding planetary collapse”

I assume corporate renewable energy developers fit into the ‘exorbitantly wealthy investors’ bucket, there. But the call for us to accept the total primacy of their profiteering as the only pathway towards sufficient clean power growth rates is badly wrong.

As profit-driven bodies seeking to be the tip of the spear for our response to the climate crisis, it should be incumbent on them to pick sites that minimise environmental impacts, and to build things in a way that massively reduces the chance of friction occurring with local residents.

That means, sometimes, they’ll have to share the benefits of clean energy production with those who live around those sites, even if it means cutting into profits. Benefit-sharing models are not the entire solution to problems of developer-community friction, but you only need to take a glance at Germany and Denmark to get an idea of how unrealised the potential is.

What really needs to occur here is the elevation of both community groups and environmentalists as valuable contributors to the collective process of siting clean energy, and ultimately, a better and deeper skepticism of those driven largely by maximising cash rewards. But Roth seems to be calling for the exact wrong groups to be disempowered.

Norway ran fast and tripped over

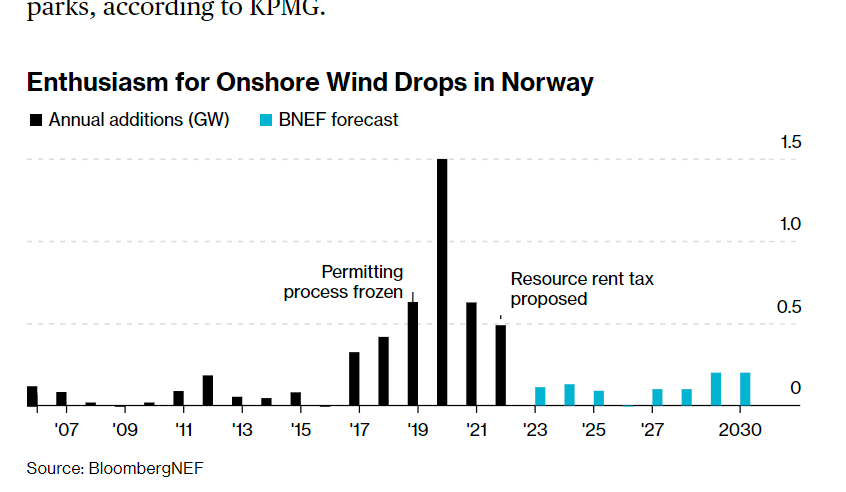

If you would like a demonstration of how this ideology can go badly wrong, please have a peek at my home, Norway. We shot up faster than any other country in the world in our wind power development; in 2019 we had one of the highest per-capita (and absolute!) installation rates for wind power in all of Europe.

After a collection of mostly foreign-owned companies rammed through several over-sized wind power projects with far too little community consultation and benefit sharing, the government froze the permitting process and it has been stuck in a rout ever since. One of those projects was found by a UN court to have breached the human rights of Sami reindeer herders and has been protested by those folks ever since, including one which famously included climate activist Greta Thunberg.

The end result: onshore wind is dead, in Norway (possibly permanently). This absolute disaster has occurred at a critical time when the electrification of transport, homes and industry is increasing, and as such, demand for electricity is rising.

Granted, Norway is uniquely tricky. Yes – we do also have some of the world’s highest levels of climate denial, and yes, loudly hating wind power is a neat way for us to avoid dealing with our own guilt as a major supplier of the stuff that causes climate disasters (orders of magnitude worse than any wind power side-effects).

But it doesn’t matter – the end result is when we desperately need a sustainable pipeline of new clean energy we failed, really badly. Acceptance of “exorbitantly wealthy investors raking in additional profits at our expense” didn’t work, here.

Sometimes people really do suck

Some of the proposed alternatives to utility scale renewables from environmental groups are worthy of criticism. Simply shifting all clean energy production onto rooftops, brownfield sites or canals comes with their own associated costs that someone has to pay, as Roth points out. These are good ideas up to a point, but come with their own limits.

I’d add that in general shifting away from wind towards solar puts even more weight on very badly unresolved human rights issues in the solar supply chain (the Nature Conservancy does a interesting piece of analysis on presenting a balanced view that prioritises environmental protection with development).

Roth is fundamentally right. We badly need large-scale clean energy in some way, shape or form. And in particular, we still need wind power (despite premature ecomodernist celebrations of solar’s unstoppable dominance). Being wedded to the system we work inside, there is simply no way of getting there soon without the presence of private corporations; though efforts to reduce this (and hopefully ultimately change it) are always vital.

It is also worth highlighting that there are clear instances where an extremely minor change to a community’s space is being aggressively opposed for blatantly selfish reasons – the anti-wind opposition to offshore projects on the east coast of Australia is a very good example of this. Absurdly, they protest these barely-visible offshore proposals while numerous coal and gas tankers frequent their horizon every single day.

Naturally, right-wing political groups are exploiting and intensifying the anti-wind movement in the Illawarra. Rich communities opposing offshore wind is a thing in the US, too. But Roth’s argument doesn’t specify rich, white coastal towns hand-wringing about faint white shapes on the horizon – it is about everything, everywhere. Perhaps more relevantly: many of these communities are filled with exactly the same wealthy investors that we are being called on to tolerate.

The burden shouldn’t fall on those carrying the most weight already

We don’t need to choose between sacrificing desert tortoises and having a fast clean energy roll-out. It really seems like the only people who benefit from this dichotomy are companies who’d prefer not to see a slight reduction in the profits they make.

Same for changes to lifestyles, which Roth mentions towards the end of his piece: “Will you eat less meat, replace your gas stove with an induction cooktop or lease an electric car?”. These are not sacrifices; they are life-improving benefits that will be spearheaded by companies while being regulated and subsidised by governments. Ditto for the German wind farms I visited that were seen as nothing more or less exciting than machines that pump money into local council coffers. There is no compulsory sacrifice here, if corporations are forced to adhere to environmental and social principles.

Wind and solar only require massive natural and human sacrifice if you fail to regulate the corporations that build them.

“Much as I hate the idea of paving over desert tortoise habitat with solar panels or refusing to remove dams that have decimated salmon populations, I hate the idea of 3 degrees Celsius of planetary warming a lot more”

“Much as I sympathize with rural towns that don’t want to live with industrial wind turbines as their neighbors, I sympathize more with my neighbors here in Los Angeles who can’t afford air conditioning and don’t want to die of heatstroke the next time the thermostat hits 121 degrees”

So the tortoise has to cop it while the “wealthy investor” soaks in the luxury of being “lived with”. Does that seem like a proposal that’s in tune with the balance of power, here?

Consider the possibility that the same environmental groups that fought bloody, multi-decadal fights for renewable policies and subsidies are not the primary antagonist against these two technologies (shocking, right?), and that they are very reasonably formulating a pathway where renewable development aligns with the reason they care about climate in the first place (environmental protection). They are not fanatical anti-wind gronks. They are recent history’s strongest and most effective advocates of wind and solar power, and it’s bloody absurd how quick that has been forgotten.

Consider too that objections to big wind and solar are spread across a distribution of reasons and motivations, rather than the lazy, single-minded blanket-term of NIMBY, and that the pathway to reducing friction at clean energy sites has no option but to engage with that complex spread.

And most of all, for what unavoidable sacrifice remains, latch it to the back of those most unburdened already. No, that is not the natural world, under siege like never before, or rural communities suffering from fossil-fuelled energy crises and financial stress.

How about those “exorbitantly wealthy investors raking in additional profits at our expense”? It’s a shocking thing to read Roth propose a muted acceptance of profiteering while demanding nature and community take the weight without complaint.

The wealthy and the powerful are the ones that should be sacrificing even a tiny fraction of that wealth if it means achieving a clean energy transition that is both fast and prolonged. They are the ones who need to “get over” the blunt primacy of shareholder value creation and be forced through regulation and taxation to care about deep, sustained decarbonisation that aggressively minimises social and environmental sacrifice, and maximises co-benefits as widely as possible.

If you are freaked out about the ever-ramping impacts of fossil fuel use, you should care deeply about how to ensure wind and solar develop real, rock-solid staying power in combination with an increased growth rate.

And if you care about building coalitions, elevating voices and fostering conversation, do not in any circumstances let your opening gambit be “GET OVER IT”.