Big cars are dead weight dragging down climate policy

In the future, the idea that we moved around in a box powered by exploding chemicals will be funny, and quaint, but the combustion engine won’t fade from memory for a long time. It should be sooner, but we’ve started very late. Things are, at least, starting to move.

Recently, Australia’s government released a draft policy designed to discourage high-emissions vehicles being sold by car manufacturers. A fuel efficiency standard has been pinged around policy circles for at least a decade and a half in Australia. And while this proposal won’t start until 2025 (just prior to the next election), late is probably better than never.

It has been generally welcomed by trades associations, car manufacturers and climate groups, with mild reservations from some fossil car lobby groups and half-hearted backlash from the political opposition. Of the three policy options Labor present, fossil car sellers want ‘slow’, the Labor party wants ‘middle’, EV car sellers and climate groups want ‘fast’, but it’s rare to find any serious player who doesn’t want it to happen at all.

And rightly so – it shouldn’t be blocked. It’s a useful piece of policy, and it’s long overdue. If it passes in its current form, it’ll put in place a much-needed basic pollution standard for cars. When you view it in isolation, it seems like a decent consumer regulation that’ll help introduce more affordable cars into a car-dependent country.

This is where, in discourse on this policy, the discussion ends. There are a bunch of questions that you won’t see asked, like: Does it meet the urgency of the climate crisis? Does it have loopholes that it doesn’t need to have? Does it tackle the root cause of rising vehicle emissions?

It does what it says on the box (the box says: ‘not enough’)

Labor’s proposed fuel efficiency standards have a lot to like. A lot could have gone wrong here: the car industry’s proposed ‘super credits’, weaker efficiency targets, even slower timeframes, or SUVs mixed up in the ‘light commercial vehicle’ category. But being thankful it wasn’t worse shouldn’t stop you from asking how it should be better.

We can look to their modelling for some insight into its climate impacts, but there is a caveat. It is a problem that Labor aren’t releasing any detailed assumptions about how it reached emissions reductions numbers in its policy document. For now we are just going to have to take their word for it. But keep in mind this is a black box: I am going purely by what they’ve included in the document, with no way of interrogating how they got it.

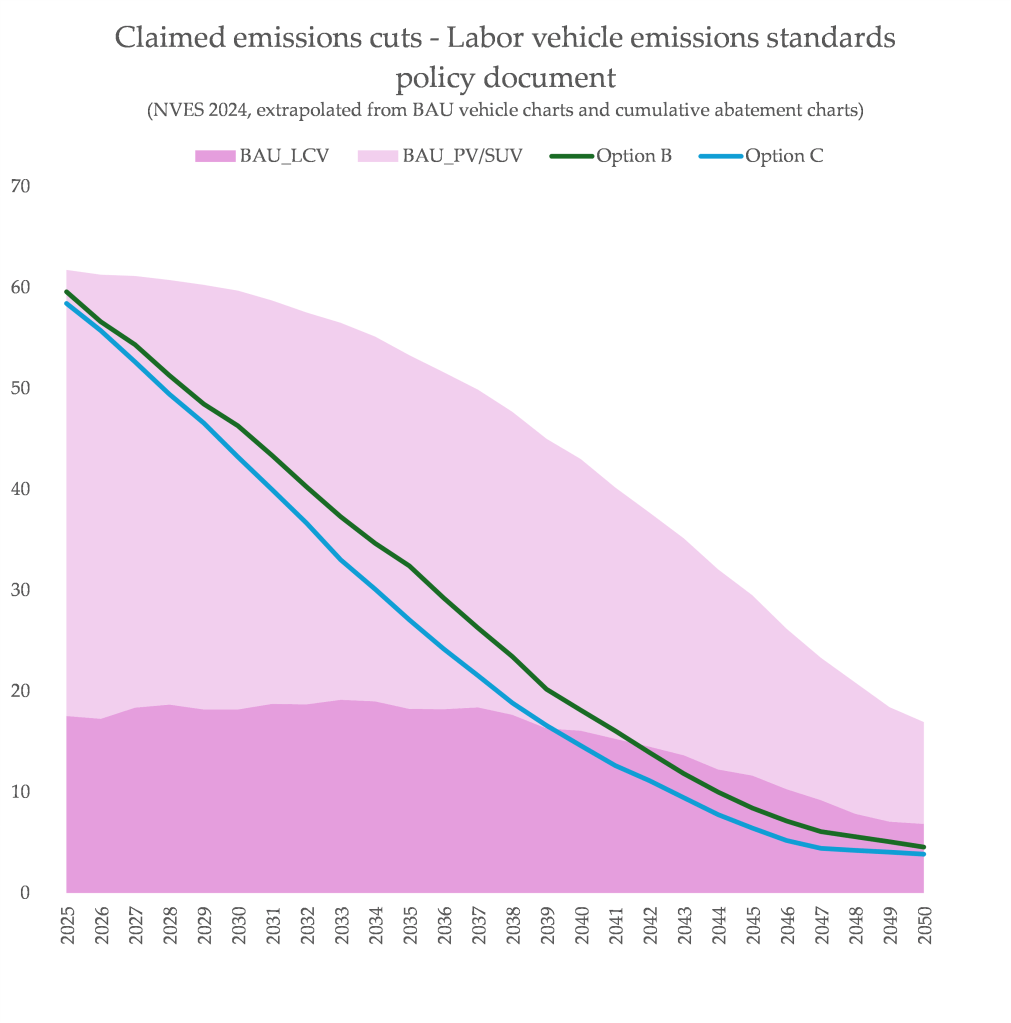

With that in mind, when you zoom in, their claimed effect on absolute greenhouse gas emissions from only cars and “light commercial vehicles” looks quite substantial. For all emissions from cars and trucks, Labor claims the policy avoids about half of what happens by default, up to 2050:

Zooming out is a different story.

Australia has a target of a 25% reduction from 2005 levels in its fossil greenhouse gas emissions. You may have read that it’s 43%: that’s if you include deeply unreliable and ever-changing land-use data (I have been banging on about this for a long time, so kudos to Climate Action Tracker for getting it more attention recently and it sucks that the EU adopted this strategy a few weeks ago).

First, context. Back in 2021, just before the election that they won, Labor released a document outlining their climate plan, including a 2030 target of 90 MTCO2-e for the transport sector. In December last year, Labor added detail to these ambitions by releasing a scenario that modelled their power sector and transport sector policies against a ‘business as usual’ projection.

When Labor released their new vehicle emissions intensity proposal a few weeks ago, they also included a modelled guess of the volume of emissions avoided thanks to it. By my reckoning, it doesn’t vary from the guesses they’ve published before – a much steeper decline for the transport sector than business as usual:

Without any new policy, by 2030 Australia’s transport emissions will be 66% higher than 1990 levels. According to Labor’s modelling, this policy will pull that down to around 49% above 1990 levels, landing right on Labor’s old climate target.

This is what their claims of climate effect of their policy looks like in the context of Australia’s total greenhouse gas emissions (excluding land use, of course):

Despite the Labor government submitting to UNESCO that Australia will upgrade its climate targets to align with a 1.5C global target, Climate Action Tracker‘s modelling shows quite clearly that Labor’s policies are very, very, very far from that, and that their flagship policies in power and transport only creep a small step towards deep cuts:

An efficiency standard for new cars doesn’t cause deep cuts in the transport sector; most of which remains untouched by Labor’s climate policies. According to their modelling, it does do something. But in context, this tentpole policy doesn’t do enough.

There are reasons to suspect that it won’t even reduce emissions as much as they claim: primarily because it does nothing to challenge the key cause of rising transport emissions and could even worsen it.

The car bloat problem

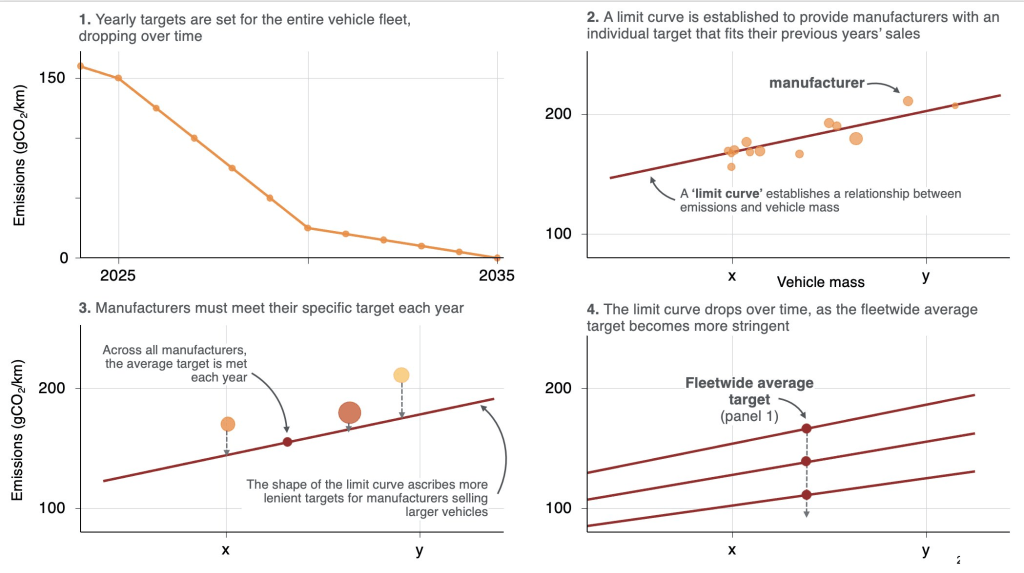

Labor’s policy comes packaged with what is now a relatively standard feature of emissions standards in places like the European Union and the United states: a formula that allows higher emissions per kilometre based on the weight of the car.

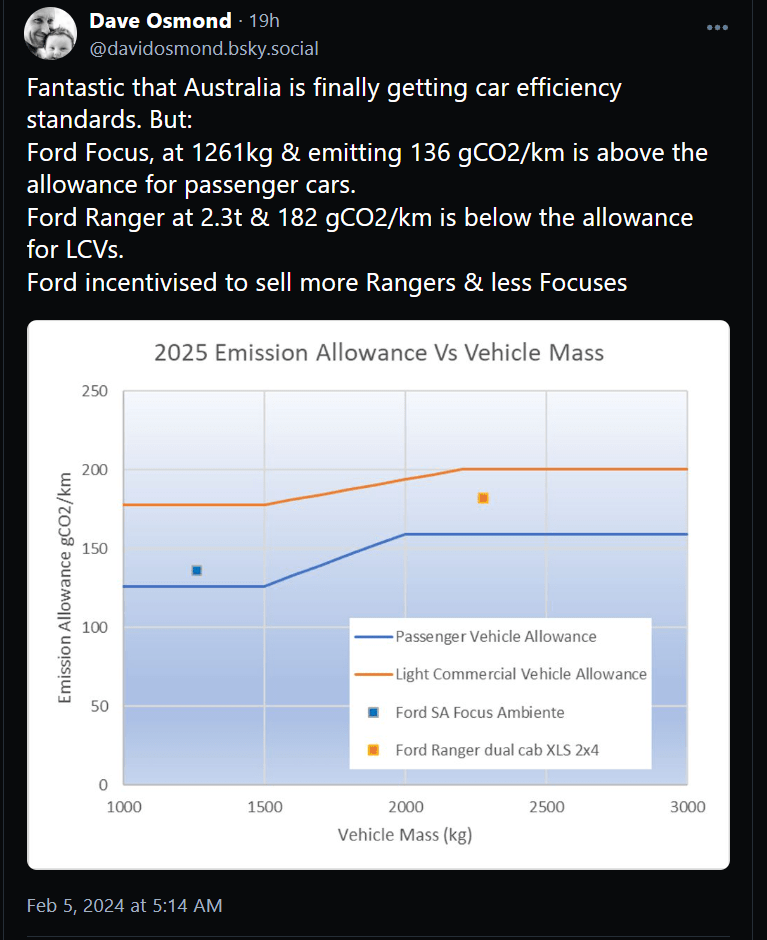

David Osmond first posted about this a few days after the policy came out, and raised the alarm that even with “break points” that cap the adjustment, it is still beneficial within that band for a car manufacturer to sell a bigger car:

Over at Elon Musk’s website, “X”, the Grattan Institute’s Lachie Fox argued that concern is misplaced, because while that relationship exists, there is still a fleet-wide emissions intensity cap that falls lower and lower each year – ie, they won’t be able to enlargen cars fast enough considering how fast the ‘headline’ target drops.

He’s not wrong: the emissions intensity standard does decrease, year-on-year, in the plan. There indeed a cap on emissions intensity, and if you breach that cap, you have to buy expensive credits from companies who were under it.

But there is no cap on actual emissions. In practical terms, it means that many of the climate benefits of this policy get cancelled out if:

(a) manufacturers sell more cars, or

(b) they sell bigger cars, or

(c) people drive more kilometres in cars

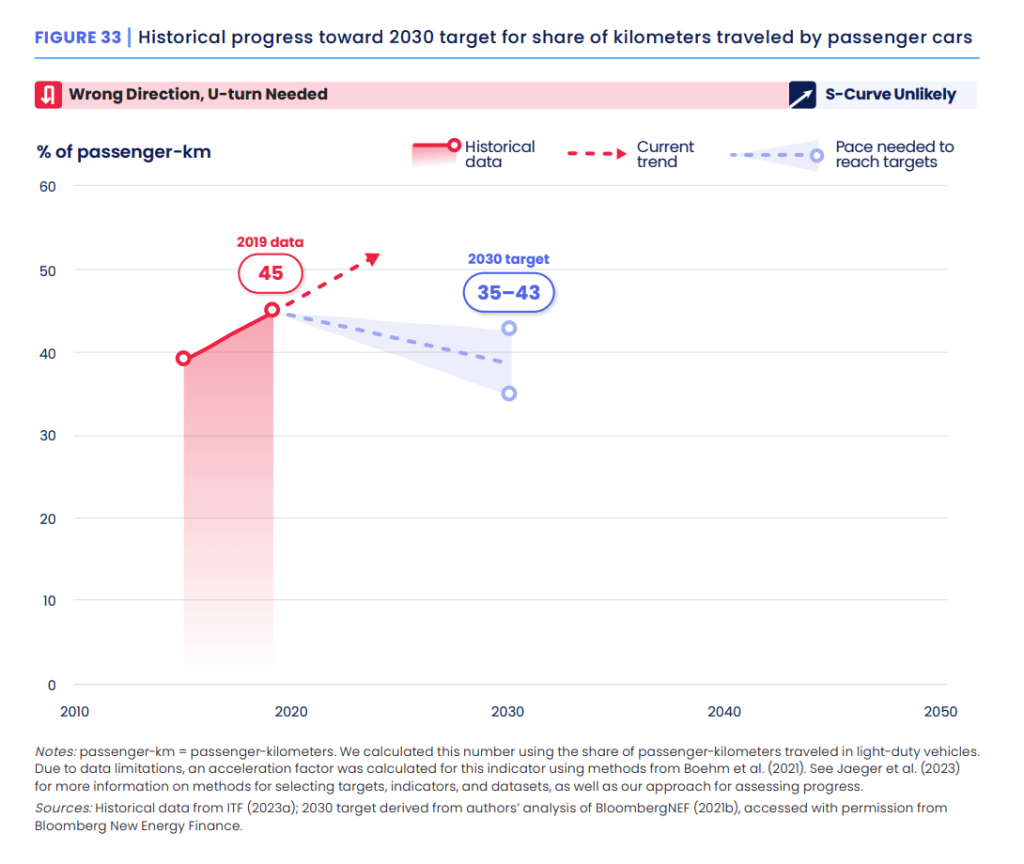

Or all three. Well – all three have been happening fairly consistently, not just in Australia but around the world. Reliance on the passenger car is worsening, according to the latest ‘State of Climate Action’ report.

In addition to this, cars are getting bigger and heavier, and the absolute distance driven in those cars is increasing, too.

All this together means gains in the efficiency get swamped by more cars, bigger and driven more often. It is like trying to brush a flood back uphill with a broom: yes, you’re probably doing something, but truly, you are missing the big picture.

We can see this exact problem playing out in the two jurisdictions that I’ve seen regularly cited as inspiration for Australia’s standards: the European Union and the US. Both allow weaker targets for heavier cars, and both very much favour the approach of an efficiency standard, to incentive cleaner car sales.

Both regions are also suffering from the problem of ‘car bloat’, where the more profitable approach of selling ever-bigger cars to consumers remains unrestricted by the emissions policy.

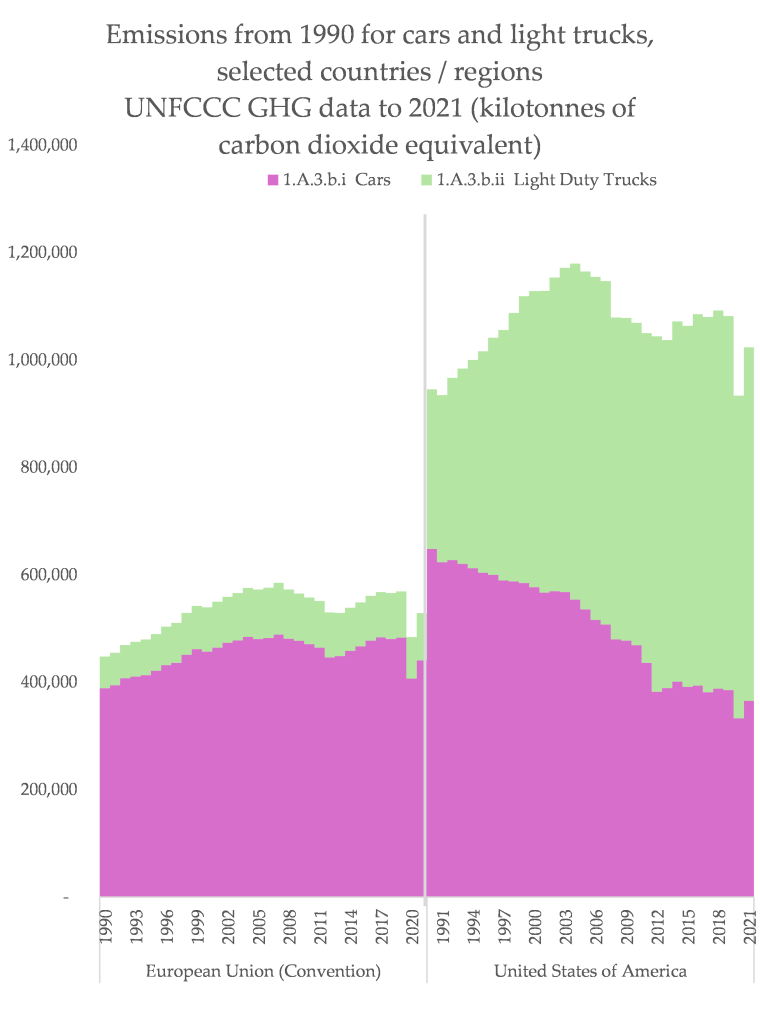

Since 1990, road vehicle transport emissions in the EU and the US haven’t risen as much as Australia’s have. But both are not seeing sustained reductions in emissions, and the problem of emissions shifting to the weaker-regulated ‘light duty truck’ category in the US is particularly stark:

When you look only at efficiency targets, car manufacturers are meeting them all without breaking a sweat, and the emissions intensity of cars is falling across Europe. In the US, fuel efficiency has doubled since 1975 and the country is looking to upgrade and extend its standards.

But when you look at absolute emissions, the EU is not on track to meet its new climate targets in the transport sector, and total US transport emissions rose last year for the fourth year in a row. As the Guardian recently reported:

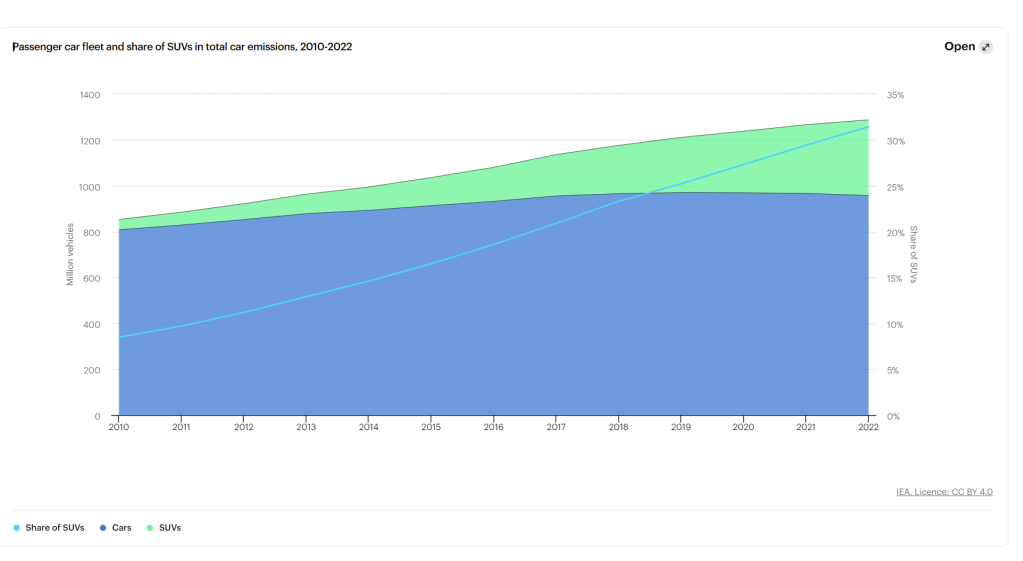

“Emissions from the motor sector could have fallen 30% more between 2010 and 2022 if vehicles had stayed the same size…the size of the average car ballooned as the trend for SUVs took off”

It’s clear that while these efficiency standards have done something, they are very far from having done enough. And a big part of the reason car bloat has been let through the gate has been the mass adjustment loophole. As Transport & Environment (T&E) wrote in 2021 of the EU policy:

“This loophole is not justifiable on climate, social justice, or technological grounds and is one of the principal reasons for the surging sales of heavy and highly-polluting SUVs across Europe”

“As the mass-adjustment mechanism rewards heavy fleets with a weaker target, it has fuelled the continuous rise of SUVs observed in the last decade (from 4% in 2011, to 26% in 2016 and 39% in 2020)”

They were, in 2022, among 53 NGOs and civil society organisations calling out a range of loopholes, including mass adjustment.

Australia’s government seems at least somewhat aware of the problems here. They include a ‘break point’ at which the emissions intensity target ceiling stop rising once cars get past a certain weight point. And unlike the EU, there is a tighter timeframe between calculating each manufacturer’s ‘reference mass’ and each year’s target.

These are slightly effective attempts to patch up the fundamental problem here: in the rich western world, climate policies for cars are designed to dance the intense desire car manufacturers have to sell ever-bigger cars. And that desire is directly responsible for a massive climate impact.

The coal-fired power stations of the road

As the International Energy Agency reported recently, “between 2021 and 2022, oil use in conventional cars, excluding SUVs, remained roughly the same, but the oil consumption of SUVs globally increased by 500 000 barrels per day, accounting for one-third of the total growth in oil demand”

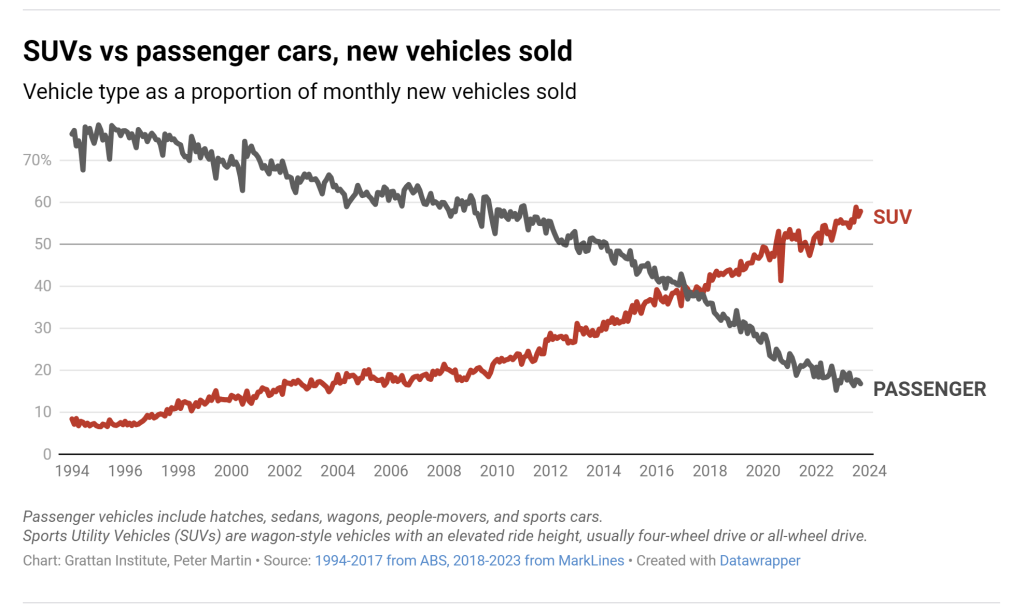

This problem is really bad. Cars in the UK and the EU are growing 1cm wider every year. In Australia, the trend is particularly intense. SUVs made up more than 50% of new vehicles sold in 2022. They now out-sell ‘passenger cars’ three to one. Standards Australia is actively considering widening the size of a standard parking spot. Concurrently, Australian road deaths are reaching record levels, with the skyrocketing prominence of bigger, deadlier vehicles an obvious factor.

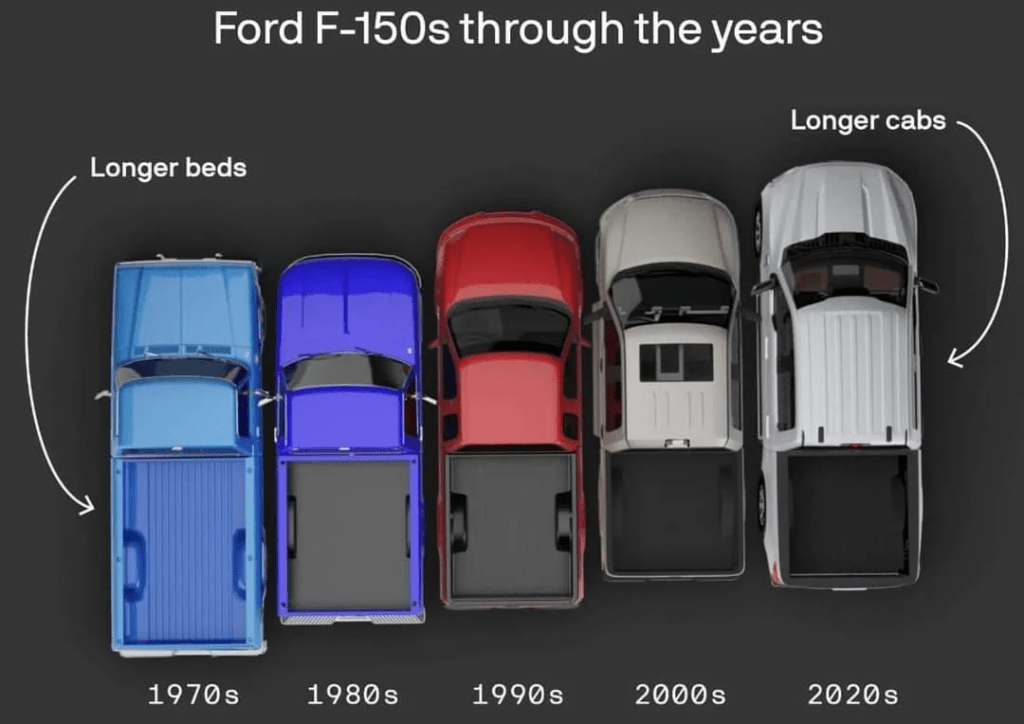

“Light commercial vehicles”, incentivised by generous tax concessions (some thankfully ended recently), account for one in four sales. These utes (utility vehicles) used to have longer trays, but have evolved to have significantly larger cabins, essentially becoming a family car (rationalised as required for work, in the same way 4WD/SUVs are rationalised as required for weekend recreation).

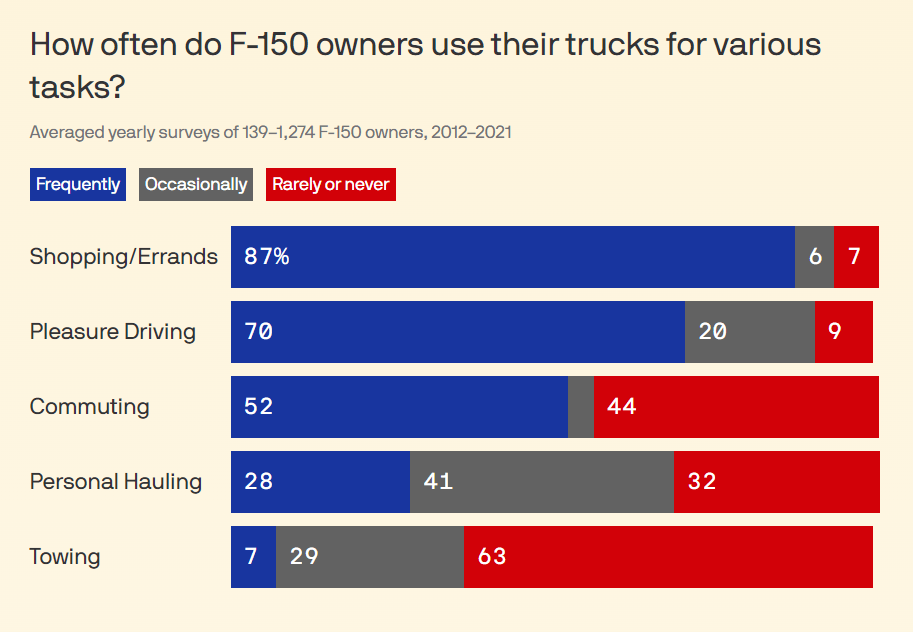

To demonstrate this weird mythology, the Australia Institute did a survey that showed that the number of utes in Australia outnumbers actual tradespeople by around 1.5x. The number of SUVs purchased outnumbers the number of caravans owned by 5x (lol). It’s a similar story in America:

This change hasn’t happened due to some organic explosion in work and recreation across western societies. Demand for road tanks has been actively manufactured by car companies, with zero regard for the immediate cost to nature, and to human life and health.

Recently, a UK advertising regulator pinged Toyota for an ad that “condoned the use of vehicles in a manner that disregarded their impact on nature and the environment … they had not been prepared with a sense of responsibility to society” – the ad was shown in bus stops in London. Australians have noticed a similar thing:

The incredibly intense drive car companies have to sell massive cars hasn’t changed in the electric era. Fattening profits to the detriment of public health and safety is just too tempting. The pathway of a bloated electric future means emissions that fall far too slowly, and various other social problems that get even worse.

As you can see below, from 2019 to 2022, the share of electric vehicle models has almost universally shifted towards a higher share of big cars, with the US in particular jumping from ~25% SUVs in EV models to ~75% three short years later:

This is bad for a bunch of reasons; primarily the sheer climate impacts of oversized car batteries. At the launch of the electric Ford F150, US President Joe Biden, gazing at the ‘skateboard’ chassis of the car, said “I was down a the plant in Georgia. This battery doesn’t look much smaller than the one they’re putting in the buses nowadays”. The Ford staffer laughs awkwardly and responds with “yes, it’s a very large battery”.

Manufacturing batteries is extremely energy intensive and the bigger they are, the worse the energy hunger. The process for extracting the raw materials used in batteries remains badly compromised, with several clear instances of human rights abuses in supply chains – experts have called for smaller cars and better public transport so the pressure on supply can be eased, and human rights issues can be addressed.

Bigger EVs also consume more power in use: higher power demand means new renewables end up meeting that demand instead of cutting down into fossil fuels. And electric SUVs are heavier than combustion-engine SUVs, significantly worsening all the road safety threats they already pose to us.

Solving transport emissions by very slowly swapping out huge combustion cars for huge electric cars is the easy option, for politicians, and for car manufacturers. For the rest of us, it’s painful – we end up stuck with worse climate impacts than if we made better policy.

Why make pedestrians, cyclists and those breathing air pay the cost for politicians and car companies taking the easy road? Why refuse to challenge the car companies in their unstoppable quest to sell bigger and bigger cars?

This policy does something. But in all likelihood, it’ll mimic European and American failure to tackle the root cause of rising emissions; resulting in insufficient reductions and stagnating or even rising transport emissions.

Good climate policy can be profoundly popular (if it’s done right)

Last year, when I wrote up a four-part essay series on the Australian government’s climate policy shortcomings, I predicted loopholes around car bloat would feature in their transport policy:

“There’s a good chance that the car industry’s lobbying could also end up accelerating an already-worsening trend towards bigger, more dangerous cars……Labor need to design a fuel standard that understands and fights this – if they don’t, any climate progress will just get run down by a Ford F-150”

I am not a powerful mystic. This was just an obvious prediction based on a constant truism about Australian climate policy: it is not designed to maximise emissions reductions, but to minimise political attack.

This defensive strategy means climate policies are born shorn of anything that could trigger a campaign from opposing forces. The fear of political attack takes priority over fear of an overheating planet.

To illustrate: a central theme throughout defense of this policy is consciously highlighting that it won’t limit the availability of massive, US-style road tanks. This isn’t an embarrassed admission: it is held up as a key positive feature of the policy design. How did we get here?

There is an assumption here that the fight against car bloat is impossible to win. But car companies used their marketing magic to manifest desire for deadlier cars out of thin air. It is recent, and fragile, and the car industry is increasingly vulnerable to even small consumer shifts and regulations (and they know it).

Labor seem on some level to recognise that solidifying their chances at the 2025 election means delivering material improvements to the lived experiences of people. The consequences of car bloat – deadlier streets, more expensive car trips and worse climate impacts – are a material worsening, obscured only by the magic aura of post-hoc rationalisations instilled by advertising campaigns targeting insecure men.

Oversized cars fit neatly into the heading of “antisocial luxuries”, coined by Ajay Singh Chaudhary in his recent book, ‘The exhausted of the Earth’. And as Ajay details in the book, it turns out that these things are simply not as loved as previously thought: people prefer cheaper, accessible transport, cities designed with accessibility and freedom in mind, and of course – breathable air and a non-cooked planet. Yes, there is two tonnes of recently purchased metal in the driveways of many people, forcing them to rationalise otherwise. But they know it too: car companies hate us, the products hate us, the infrastructure hates us. It’s oppressive and crushing, not liberating, to be locked in to cars.

Ultimately, if Labor want to really buttress their political fortunes, they have to actually improve the lived experiences of people. That means keeping this policy, but removing all of the parts of it that let car manufacturers continue to enlargen cars that are more dangerous for those inside and out, are more expensive, more power hungry, and damage cities and infrastructure.

Yes, it’ll trigger a backlash, but if Labor can’t ever pre-empt and cope with a backlash, they are permanently incapable of ever addressing climate change at the rate required and should just admit it instead of posing as climate heroes.

The real, immediate regulatory options are numerous. Some are already underway, such as banning ads for damaging SUVs, or Paris beginning to introduce restrictions on SUV parking. Ultimately tackling transport emissions will also mean trying to reduce car reliance, while opening up major new transport options (bikes, trains, buses) that increase the freedom and improve the lived experiences of Australians. Mobility, lower-cost living, less aggression and frustration when moving from A to B: these things are noticeable upgrades in human society.

Hopefully, in the future, we’ll laugh at more than the box powered by chemical explosions. We’ll laugh at the monster trucks we used to buy cartons of milk. None of that happens until governments bring a real fight to the car manufacturers, who aren’t planning to stop profiting from harm any time soon.