Why Norway craves the worst-case climate outcome

Norway’s government strutted away from COP28 whistling happily, high-fiving other ministers from similarly triumphant fossil exporting nations. The meeting ended with a call to ‘transition away’ from fossil fuels: something that’s never featured in a COP agreement before. Hell yes! Victory lap!

As soon as the jet wheels touched down back home, our government toggled back into honesty mode: trying to expand oil and gas supply as much as possible, in the hope that the world fails its climate goals so hard that it has no choice but to turn to our bountiful supplies of oil and gas.

This is our climate philosophy: be the climate change you want see in the world.

I don’t think it’s well realised just how much worse Norway has gotten in recent years, when it comes to trying to expand its fossil fuel output. I think it’s represented nicely in a dataset that came out recently, from the statistics agency.

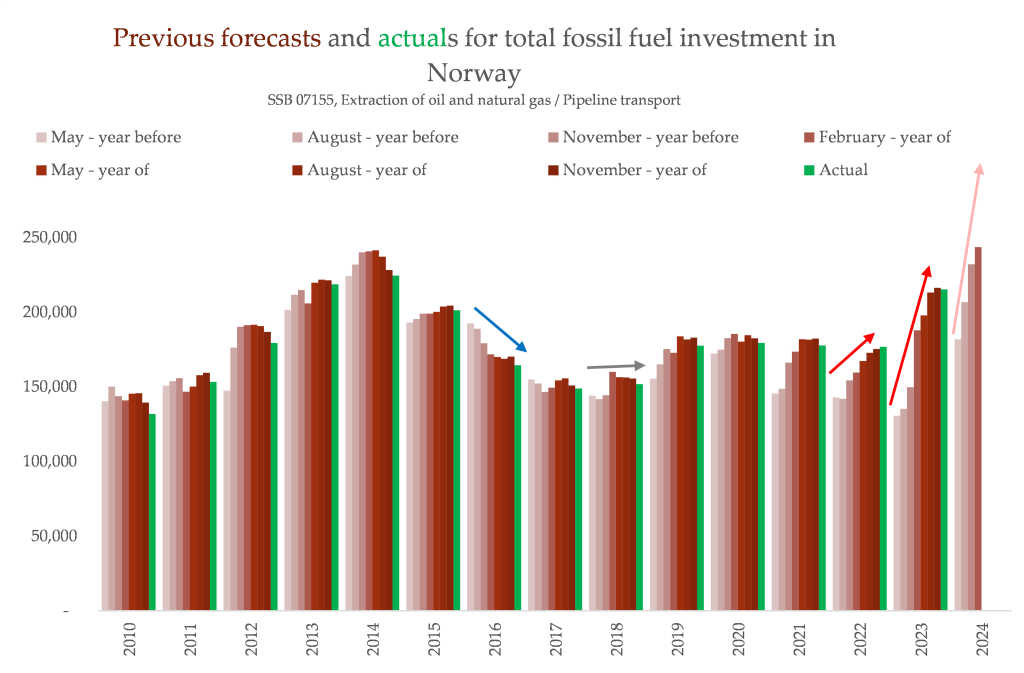

Before the end of each year, there are seven projections made for the total fossil fuel extraction investment in that year, starting in May the year before. As each forecast gets closer to the actual final end of the year, they get closer to what the actual figure ends up being. In May 2022, for instance, we get the first projection for what all of 2023 will look like.

Generally, these forecasts haven’t been hugely different from the final figure. But in the past few years, things have gone haywire:

In 2016, for instance, you can see the first projection was quite high – but by the time 2016 ended, the ‘actual’ was way lower than they had originally anticipated. This type of overestimate of eventual spending on fossil fuel extraction doesn’t happen anymore.

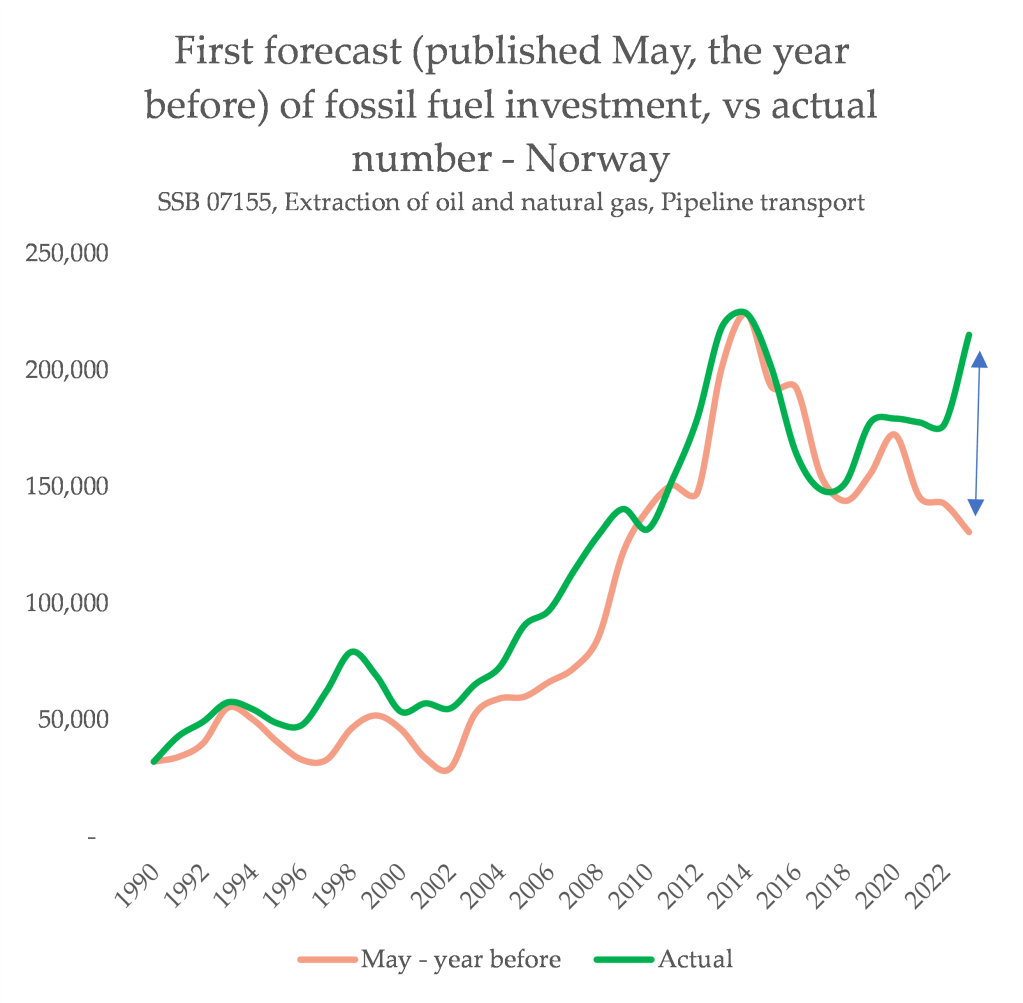

What we see now is a wild underestimate of how much cash ends up being spent on trying to get more fossil fuels out of the ground. In 2023 for instance, the first projection for that year (published in May 2022) was 130,000 million NOK. It ended up at 215,000 million NOK – 60% higher.

While systemic underestimates of fossil investment have happened before, for 2023 there has never been a mismatch between the first forecast and the actual number this large:

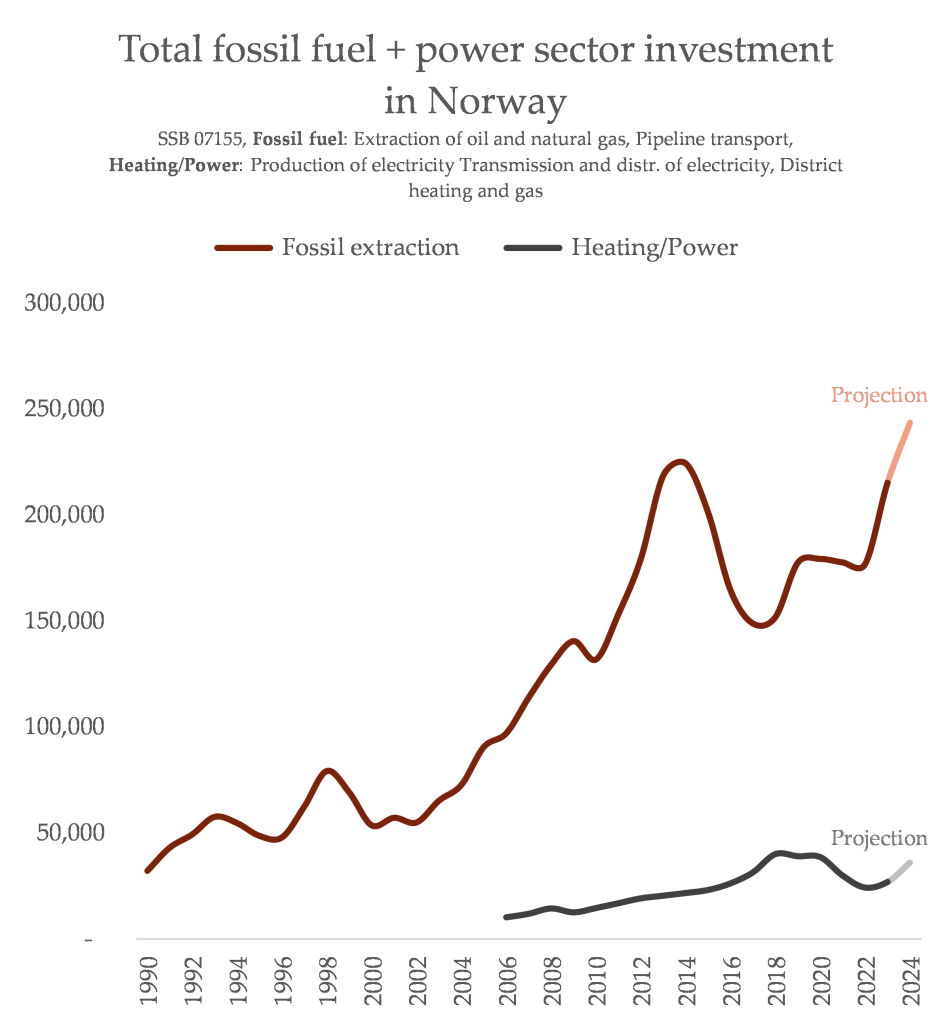

The projections for 2024 are already suggesting Norway will spend more than it has ever spent on new fossil fuel supply – and given the past few years, even this is probably an underestimate. Compare this to how spending in the power sector and heating have stagnated (a serious problem given our need to electrify transporting, heating and industry):

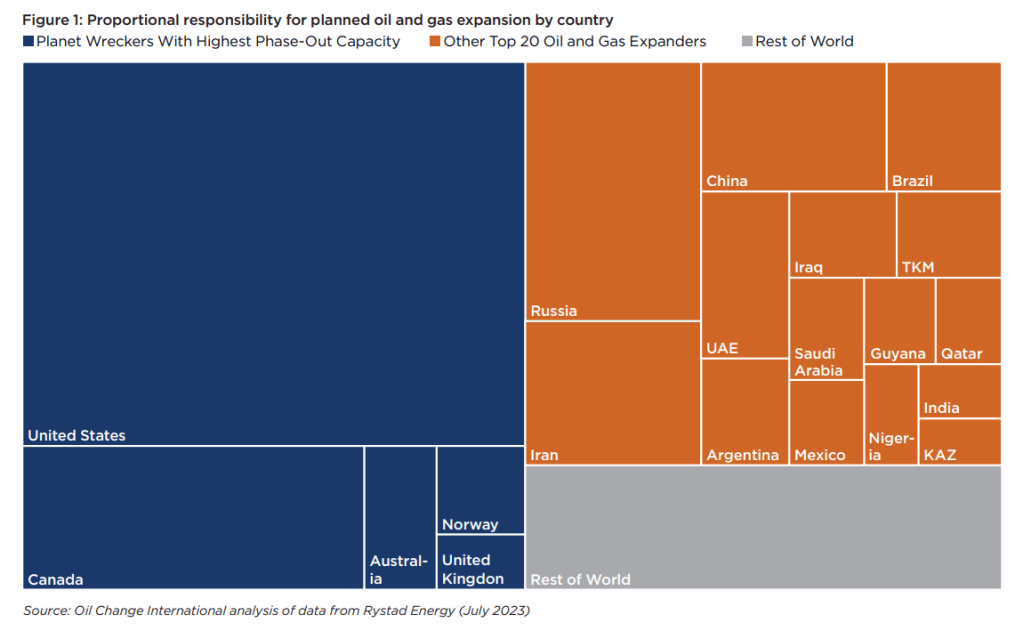

On the global stage, we aren’t quite as massive in our expansion plans as the US, or middle-eastern states. But we are part of a group of Global North countries with diversified economies, high historical responsibility for emitting and high incomes – putting us squarely in the position of being totally able to quit the planet heating product business, but actively choosing not to.

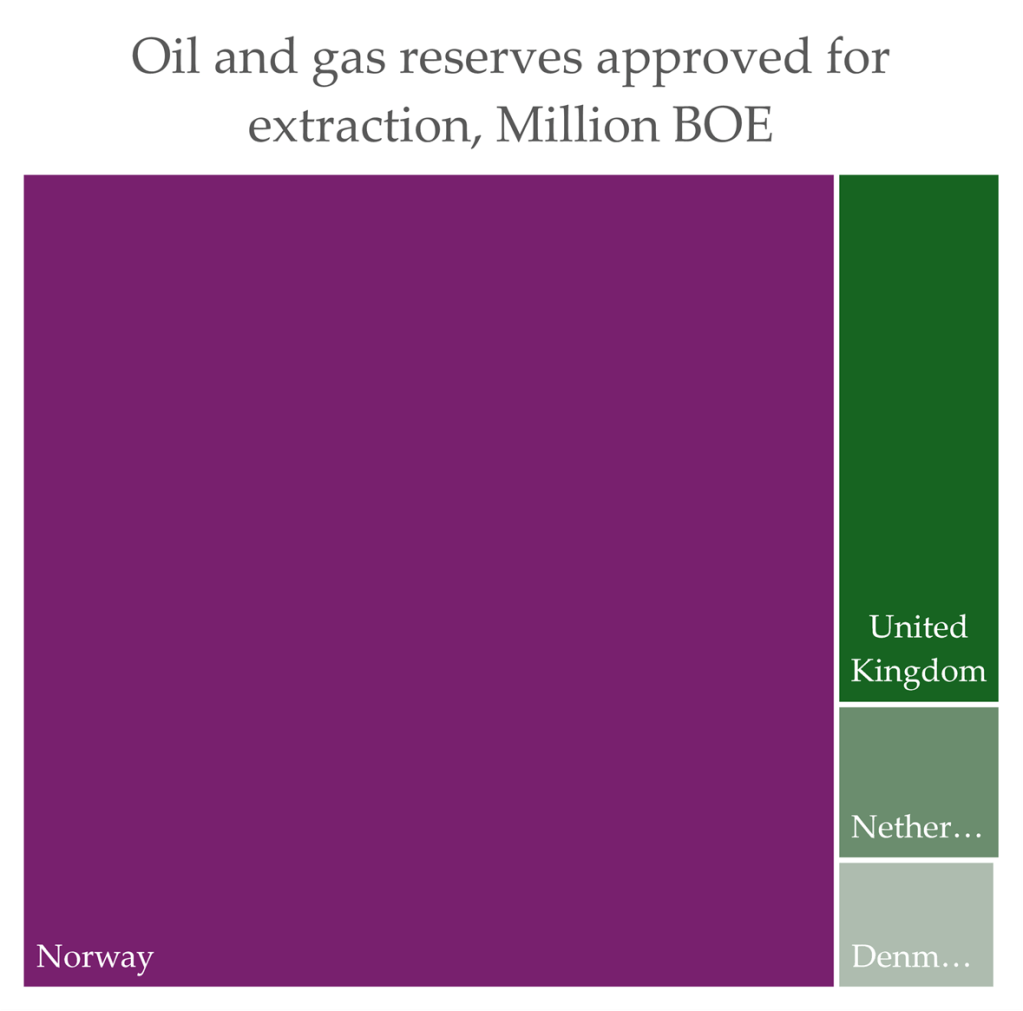

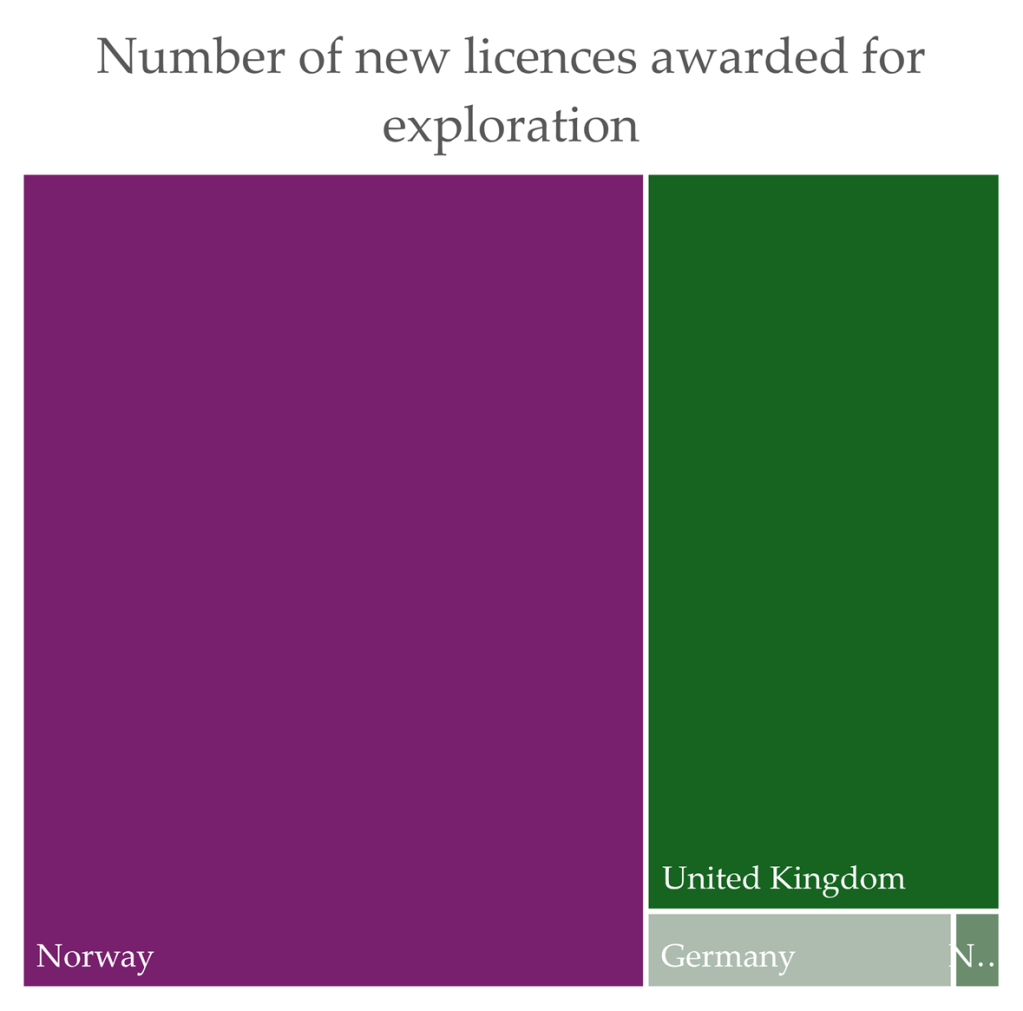

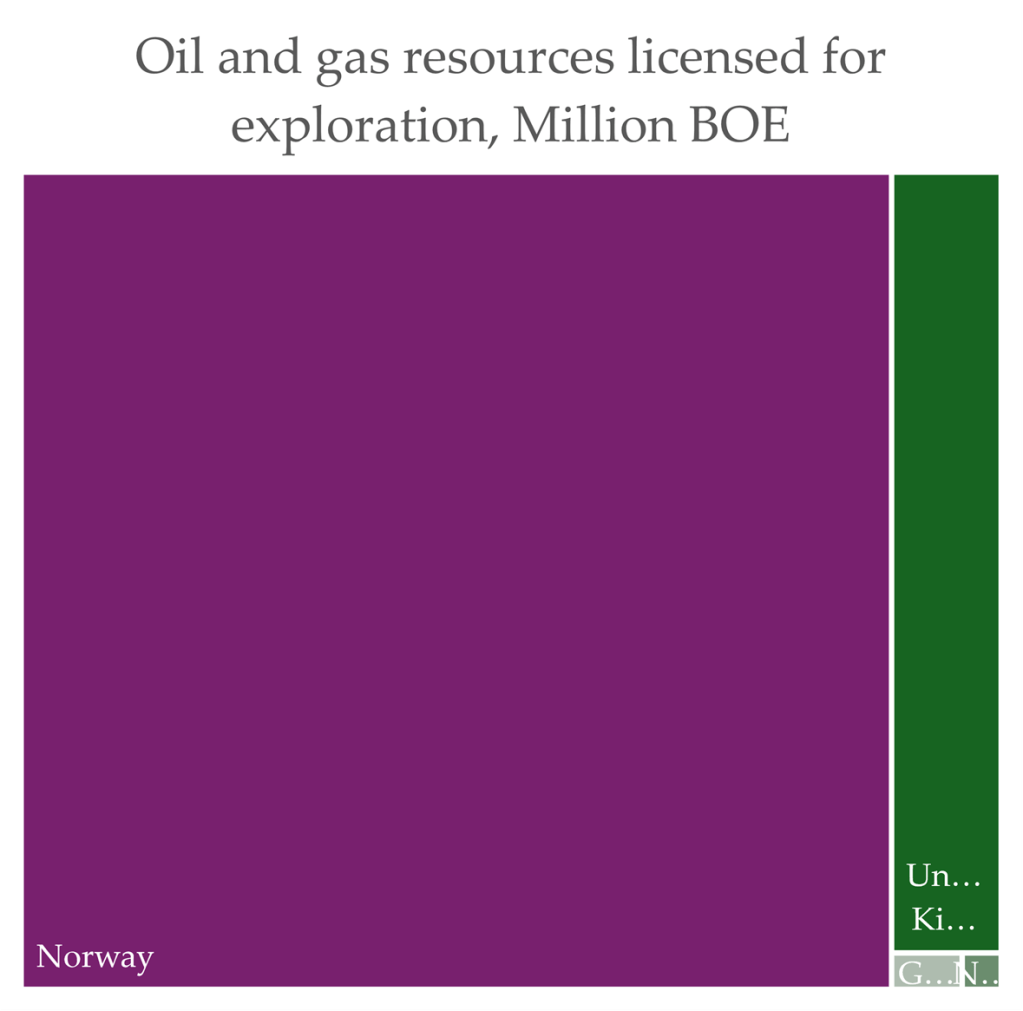

When you zoom into our our North Sea peers, we’re dominating our little corner of the world in terms of actively trying to expand production, as found in this recent report:

That’s a cool eleven cumulative gigatonnes of emissions (globally we emit around 39 a year) from Norway’s planned new fossil fuel projects, more than double the next worst (the UK, at around 5). In a recent report, Oil Change International labelled us “the face of climate hypocrisy” – these new oil and gas fields will unlock the equivalent of around 19 new coal-fired power stations worth of emissions.

In short: we are not unique in trying to expand the supply of fossil fuels, but we are certainly unique in how we convince ourselves we’re on the right side of history for doing so.

A major causal factor in our unprecedented fossil expansion is COVID19 stimulus. Norway spent $15,234 million USD on tax reductions for oil companies operating on the continental shelf; 83% of total COVID19 recovery spending. 3% went into green schemes.

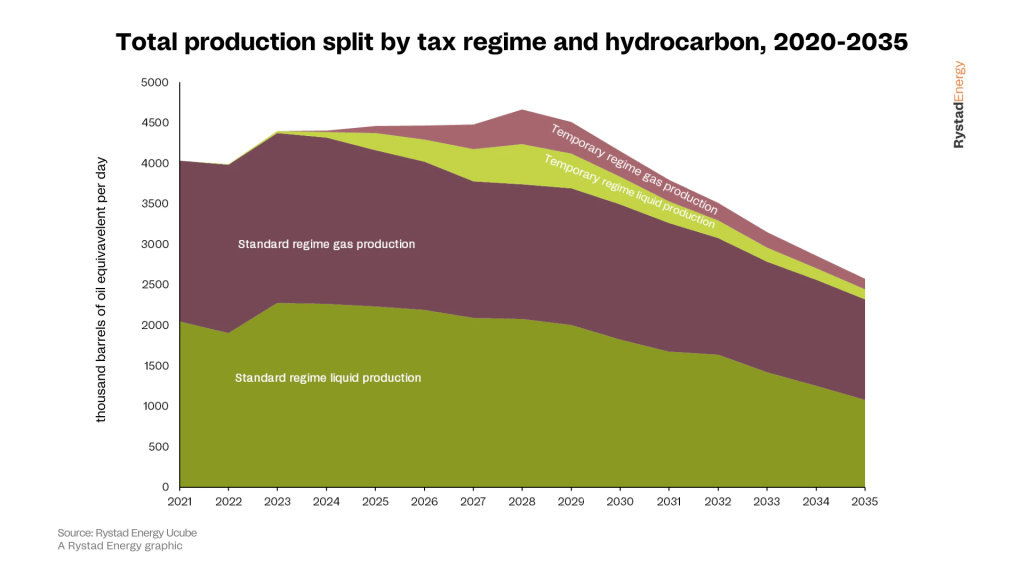

Fossil fuel industry and Norwegian government consultancy group Rystad Energy lay out nicely exactly how much Norwegian fossil fuel production will increase by, thanks to the COVID19 tax breaks. Hauntingly, they add, “Norway will need to consider if this regime is a one-off to attract investment, or if lessons can be learned for the future”.

It was sheer luck that this huge, production-expanding tax break came right before the outbreak of a war, in which a major provider of fossil gas to Europe decided to violently invade a neighbouring country. If Europe stops buying Russian gas, which brave soul will step up to keep all the combustion machinery pumping out pollution? A selfless Nordic hero stands up, and promises to serve the great need for Energy Security.

Despite having kicked off this expansion bonanza pre-war, we were handed a loud and proud moral justification for fossil expansion, when before we had to just awkwardly shuffle and stare at the ground and hope no one noticed. Hydrocarbons For Peace.

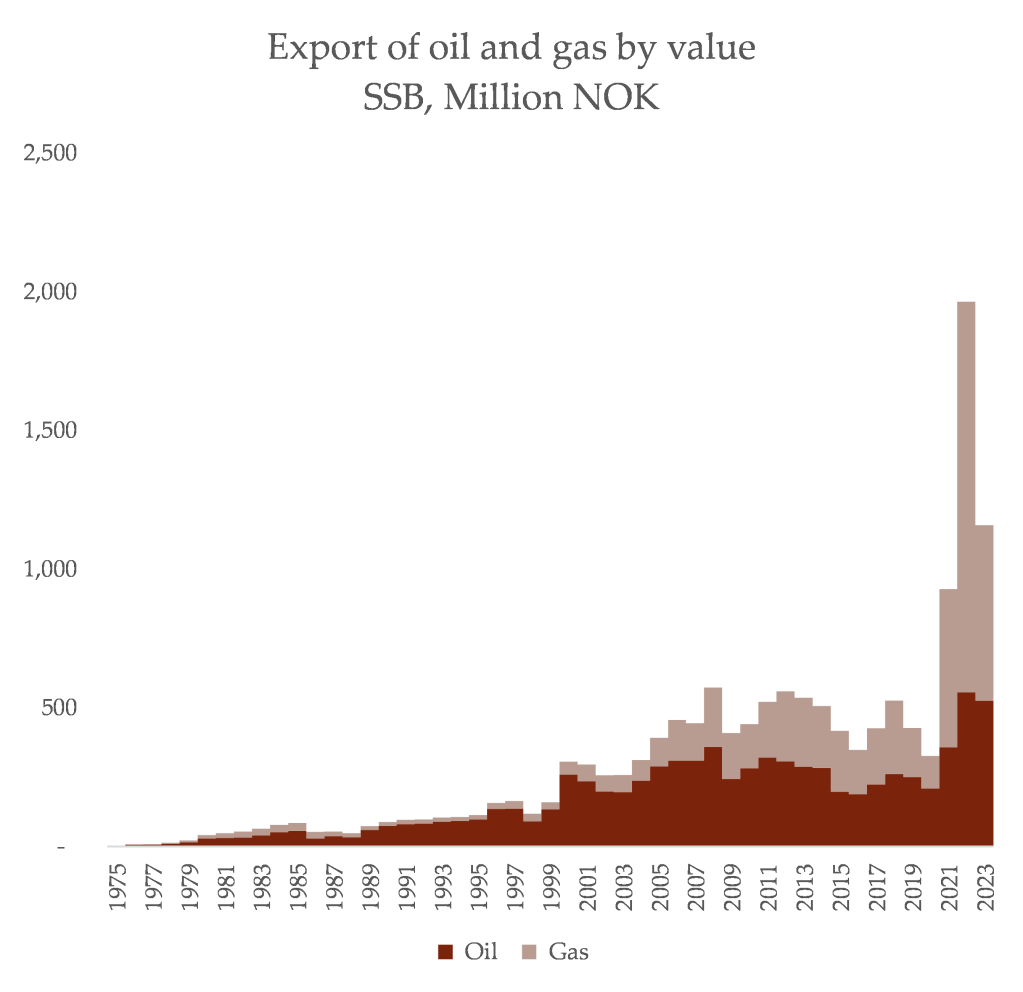

In addition to providing a heads-held-high rationale for our preexisting fossil fuel growth desires, the Russian invasion of Ukraine resulted in Norway earning more from selling fossil fuels in three years than we earned in the nine years before that:

What do we do with all that cash? Already, our planet-sized fossil profits piggy bank, the oil fund, holds $1.3 trillion USD, for a population of 5.3 million people.

A recent report from Climate Analytics showed that, for Norway, the harmful impacts of the normal use of the fossil fuels we sell works out in financial terms to roughly what we’ve stored in the national piggy bank (about $1.1 trillion USD). That is to say: when people burn the oil and gas we sell, the amount of ruin it’ll bring to the world is about the same as the benefits we accrue in national wealth.

“Given the global impact of the damages caused from fossil fuels, it should be reflected on whether fossil sovereign wealth funds should only benefit citizens of the countries of their origin. Or whether they could not substantially contribute to a global financial loss and damage mechanism to support those suffering from the consequences of the fossil business model that continues to create income”, wrote Climate Analytics.

What we should do – at the very least – is pay for the damage inflicted by the normal use of the product we sell. If we were anywhere near as Noble and Brave and Honourable as we present ourselves to be, we’d do this as a default. Part of the mythology here is that we don’t need to be responsible, because we’re going to quit this industry soon anyway.

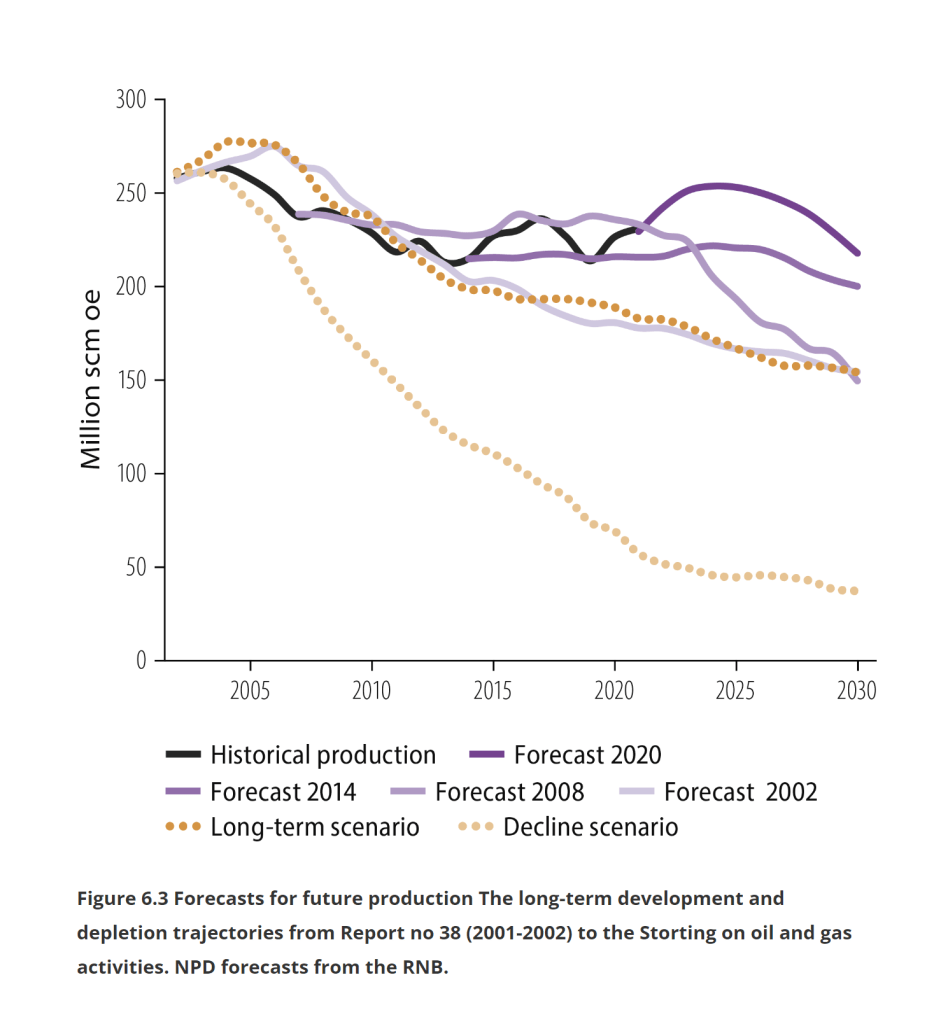

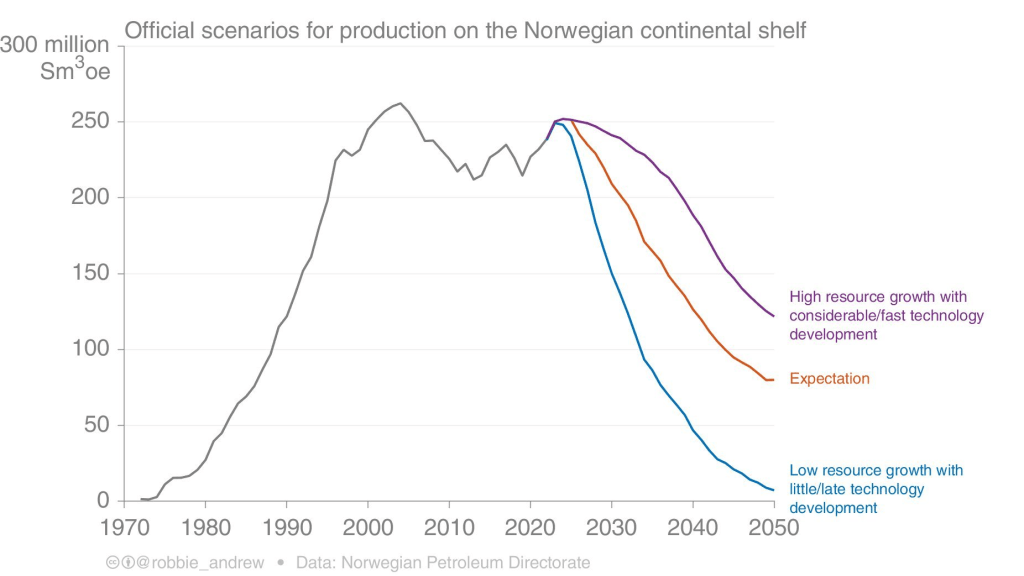

Norway’s government currently projects a fall in the amount of oil and gas we produce. That’s heralded as evidence of our transition responsibility, but it has been wrong before: Glen Peters from Norwegian climate research group CICERO highlights that we have a history of forecasting drops in fossil fuel production, while the reality remains a constantly flow of planet-heating products sold to the world. “The forecasts made have so far all been wrong! Production has not declined as the petroleum agency has predicted”, Glen said.

Which leads to the fairly reasonable conclusion that Glen states: “Based on history, there is little evidence that Norwegian oil & gas production will fall as forecast. Continued investment & technology evolution will make these forecasts wrong”.

Who’s going to buy and burn the oil and gas we plan to sell? A recent analysis by a group of climate and environment organisations found that the European Union’s demand for oil and gas is likely to fall much faster than projected Norwegian production: “If the EU meets its long term climate targets, gas supply from currently producing projects in the EU, Norway and Algeria and existing contracts are set to exceed demand by 2035”.

In short: Norway is planning for an overheating planet. We are acting on the grounds that the only way humanity can exist is by burning stuff that also kills us.

This is why our mantra is ‘be the climate change you want to see in the world’: the act of supplying fossil fuels results in more emissions than if we were to put downward pressure on extraction instead.

A group of rich, powerful people motivated to sell something will find a way to manufacture demand for it. There is plenty of evidence from the economic standpoint that increasing supply of fossil fuels will lead to a net increase in its consumption. There is also no shortage of examples of fossil fuel suppliers actively preserving or manufacturing demand for their products, because they know they need to keep supplying them to earn their cash. Fossil fuel companies still near-universally offer cash incentives for executives that grow fossil fuels.

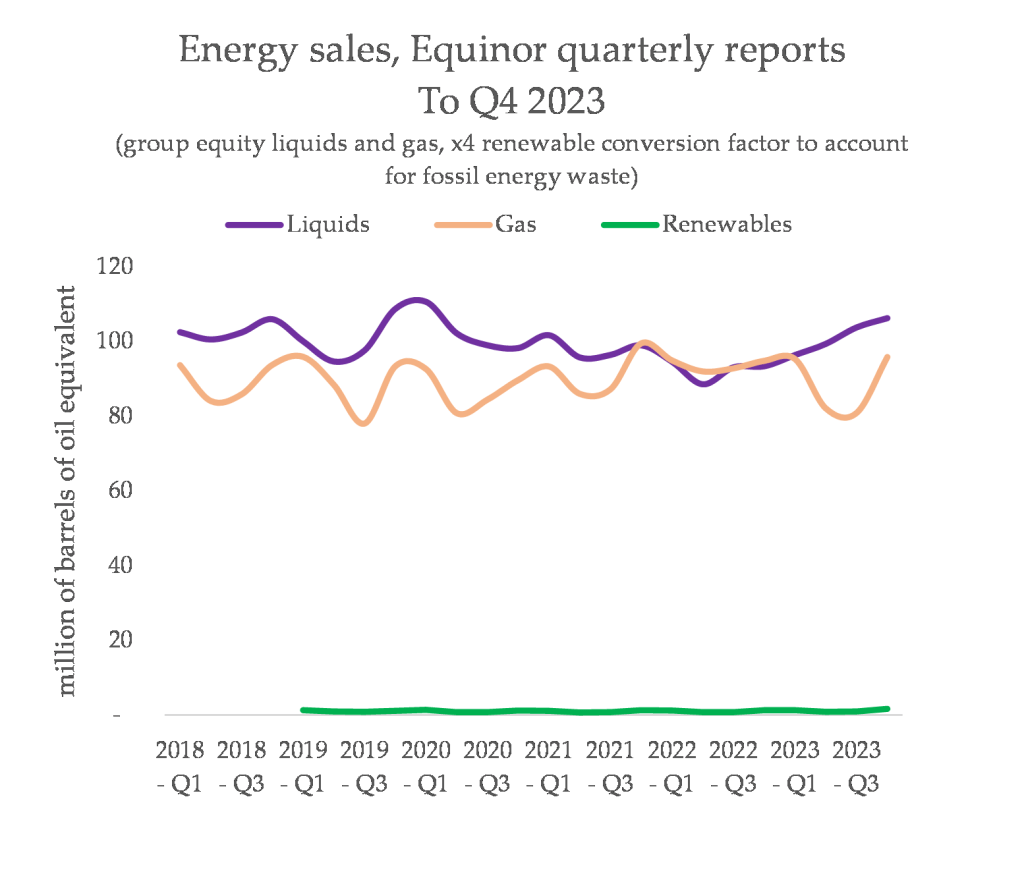

Norway’s somewhat-state-owned oil and gas company, Equinor, still finds worth in pretending to be in a state of transition away from selling fossil fuels and towards selling clean energy. But they do not walk their talk. Here’s the latest data on what they sell:

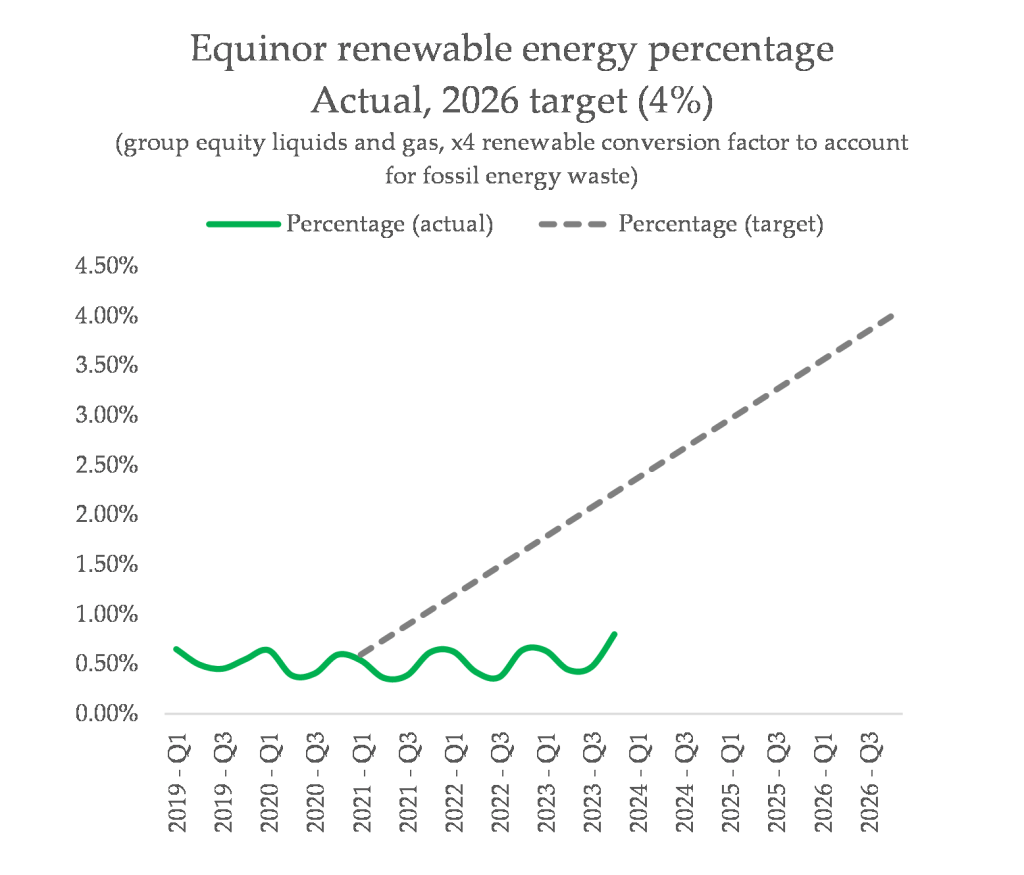

Equinor use ambitious targets to defuse criticism of its current actions, and then set about ignoring those targets until they’re forgotten, after which they’re quietly deleted. A nice example is the target they set a few years ago, to sell 4% clean energy of their total sales by 2026, which has vanished from view.

Their more recent renewable energy ambition is shown below, and in March 2022, they set a new target for carbon capture and storage that I’ve drawn up against their actual amount captured.

You get the idea, right? They want the warm glow of praise, when they tell the world how they’re advancing in climate goals. Equinor wants this as much as Norway wants this. It is one of the most fundamental sources of national cognitive dissonance.

We’re not doing great in a bunch of ways. Despite the fact we’re on track to miss our transport climate targets, we get showered with praise for our EV policies. Despite our shocking track record in building wind power that breaches human rights of Sámi peoples, we’re seen as a renewable energy leader (we are actually doing very well with heat pumps, but weirdly have no desire to brag about it).

Ultimately, we want to be seen as humble servants of fossil fuel demand, responsibly using the cash we earn to fund rapid climate action, healthcare and welfare. You don’t have to reach far to find someone who’s heard this tale and bought it wholesale. I get it: we need to daydream that villains can pivot to heroes, and COP28 leaned hard on this desire.

What we are, in reality, is a country hoping hard for failure. Fingers crossed on both hands for every single oil and gas phaseout attempt to fail badly.

If our dreams for high and prolonged fossil fuel demand come true, it’ll be a bad, bloody catastrophe for the world. We’ll sell the fuel for that fire, and we’ll keep the spoils for ourselves.