The hollowness of the 2030 targets debate

Recently, Australia’s opposition leader, Peter Dutton, promised he’d scrap Australia’s 2030 target (a 43% reduction on 2005 levels), if elected PM in 2025. He won’t reveal the replacement unless he wins. Dutton’s logic is that the existing 43% target is ‘unachievable’, (at least without apocalyptic social collapse). There is “no sense in signing up to targets you don’t have any prospect of achieving”, Dutton insists. Plenty of political journalists repeated that line, such as the ABC’s David Speers, who says “plenty of experts also believe it will be a stretch”.

The Labor government, two years in power now, claims they’re working hard to hit what they describe as an ‘ambitious’ level of reductions, something that has pulled them into a state of urgent action, which they claim they’re rising to meet.

“[Dutton’s plan] is just not a serious policy and if you don’t have a serious policy on energy and climate then you can’t be taken seriously as the alternative prime minister of Australia,” Albanese told a Guardian Australia podcast. “The point of having a target was to have ambition and try to meet it”.

These spats get framed as “climate wars” by journalists, commentators and politicians. Notably, the phrase did not get trotted out after the release of Labor’s obscene “future gas” plan, laying out export ambitions post-2050; but for this news cycle it is utterly unavoidable.

The ‘Future Gas strategy’ is a bipartisan agreement to actively worsen the climate crisis. This is the long-running climate peace: consensus between both major parties to do an eco-fascist lean into the extractivist death spiral and bleed whatever cash benefits remain from causing from climate damage.

The “climate wars” framing that activates so much excitement among a media landscape that mostly ignores climate change reveals something significant: verbal disagreements between the two parties are seen as more dangerous than the actual physical consequences of climate disaster, and significantly more worthy of attention than assessing the performance and ambition of whichever government is in charge.

There is no war, here. This is a climate pantomime. A performance crafted through data trickery and media-suited narrative tropes to create false distance between two political parties that largely agree on the vast bulk of climate policy, both reject the ‘spirit’ of the Paris Climate Agreement, and largely disagree on style.

Australia will hits its 2030 targets: no matter what happens with climate policy

Don’t worry, I’ll walk you through this one. I hope you’re comfy. Get a snack.

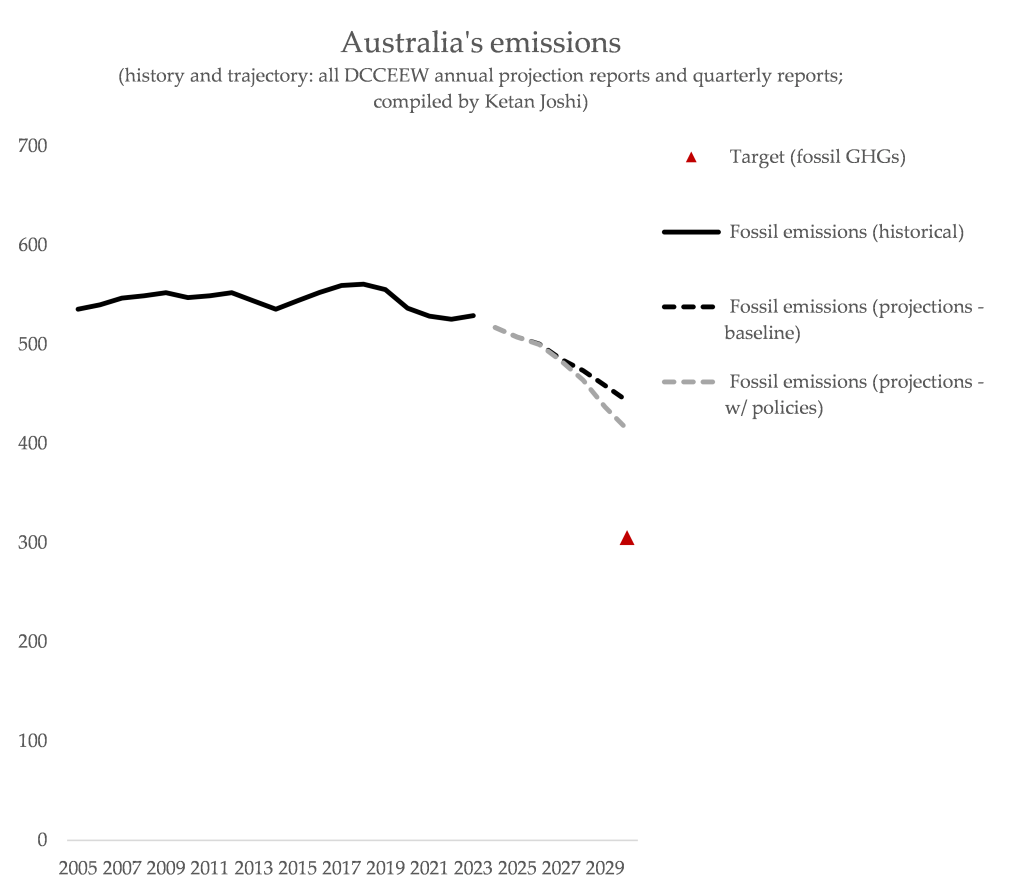

Australia’s power, transport, mining, industry and agriculture sectors all release greenhouse gases. Mostly it’s from burning coal, oil or gas (some methane gets released directly into the air, perhaps by pipelines transporting the gas, or by cows burping). This is the latest estimate of the total emissions from the burning of fossil fuels (plus the methane) in Australia, along with what a 43% reduction from 2005 levels would look like:1

Right. So we need some urgent policy heft, pulling downwards on that stubborn solid line, right? Well, the latest projections report from the government examines what happens without any new policies to reduce emissions – a decline driven largely by coal power shutdowns and new clean energy. No matter what we do (and assuming no major reversal of trends), the natural state of affairs will result in some progress:

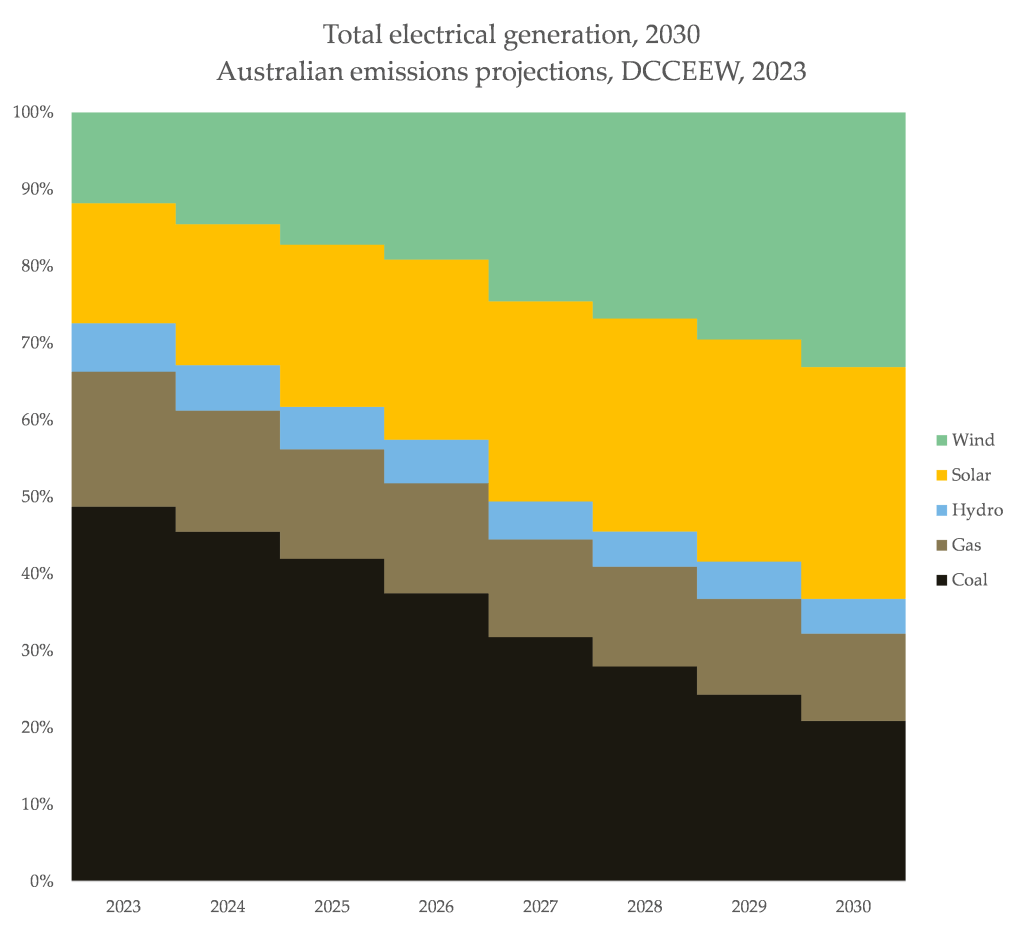

Almost all of the drop in the dotted line you see above comes from the power sector moving from about 39% non-fossil energy in 2023 to about 68% in 2030 (a cautious projection – it’s way less than the most pessimistic scenario in the grid operator’s plan for the National Electricity Market).

But, still not reaching the 43% reduction target. So the same projections report also modelled what happens if the government’s 82% clean energy target were to be met, along with the impact of fuel efficiency standards (now having passed parliament, but watered down). This is what that looks like:

Lower, sure. Again: mostly due to power sector. But still, the gap remains.

Well, guess what: we excluded a sector that the government includes: human changes to carbon stored in land.

When you plant trees, that is a human influence that causes carbon to be sucked from the air. When you cut down a bunch of trees and burn them, that releases carbon. If the land-use figure is negative, that’s more of the first. When it’s positive, more of the second.

The idea here is that when you dig up gigatonnes of carbon from deep underground, it can all just be sucked up by trees on Earth’s surface, and so you can smoosh the two types of data together into one “net” figure. To be clear: this is an extremely wrong thing to do. As Earth scientist Kate Dooley wrote a few days ago (emphasis my own):

“Another problem with net accounting is it treats all carbon as equivalent, meaning a tonne of carbon sequestered in trees compensates for a tonne of carbon from burned fossil fuels. This has no scientific basis. Carbon dioxide emissions are effectively permanent, as the buried carbon we dig up and burn stays in the atmosphere for millennia, while carbon in trees is temporary in comparison.

As trees grow, their carbon storage compensates for earlier logging and clearing emissions, which is an important climate benefit. But we’re not comparing apples and apples – forest carbon doesn’t compensate for fossil fuel emissions”

It has no scientific basis, but it obviously has a political one: including land-use completely changes the narrative on emissions.

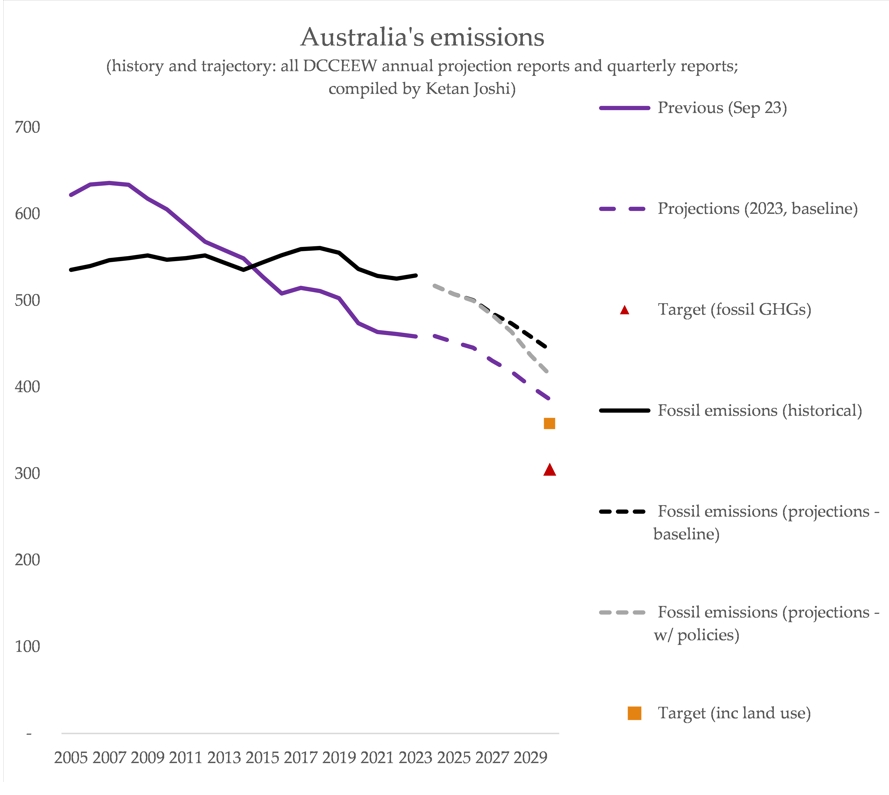

Recent emissions look lower, and the base year of 2005 gets shifted much higher. That squeezes both ends and that means the 2023 projections only see a small gap between the target and the business-as-usual future:

Well, add in the 82% clean energy target and the fuel standards, and guess what? Target (essentially) hit:

The 2023 projections data essentially scrapes through to thanks almost entirely to the inclusion of land-use data and partly due to the power and transport sector policies.

Here’s the problem: the power sector transformation isn’t really going as planned. A policy vacuum for the four years since the end of the renewable energy target in 2020 has resulted in some of the lowest rates of clean energy investment in years. Clean energy generation growth is decelerating, and that paired with growing demand means emissions are rising again. As Nine wrote:

“The government set a target in law last year to reduce Australia’s emissions by 43 per cent by 2030 but is facing significant doubts about whether its policies will reach that target because of delays to major renewable energy projects and the construction of new transmission lines.”

Others, like the Guardian’s Karen Middleton, cite a 2023 Climate Change Authority report that (correctly) points out that clean power growth isn’t on track to achieve an 82% target.2

Considering the projections only just scraped through assuming full success on the 82% clean power goal: being off track for that means there’s a problem right? A few weeks ago, you might have been right. But you aren’t anymore.

So that land-use data I mentioned? Not only does it beautify the emissions trajectory and weaken the target when you apply it, you can also historically revise that land-use data as your “methods” improve. It isn’t just magic: it becomes more magical every single year.

Revisions to the “methods” used to measure land-use emissions have, every single time for at least the past five years (and probably longer before I began tracking it), been auspiciously and delightfully spitting out results that exactly favour the narrative of the government in charge; putting Australia “on track” to achieve every previous target even when fossil emissions fall too slow, stagnate or rise.

And as I wrote in this piece, the most recent revision to land-use data has the most significant ever impact on Australia’s reported greenhouse gas emissions: a “reduction” equivalent to the actually-real reduction of the past five full years of all new wind and solar built in the country.

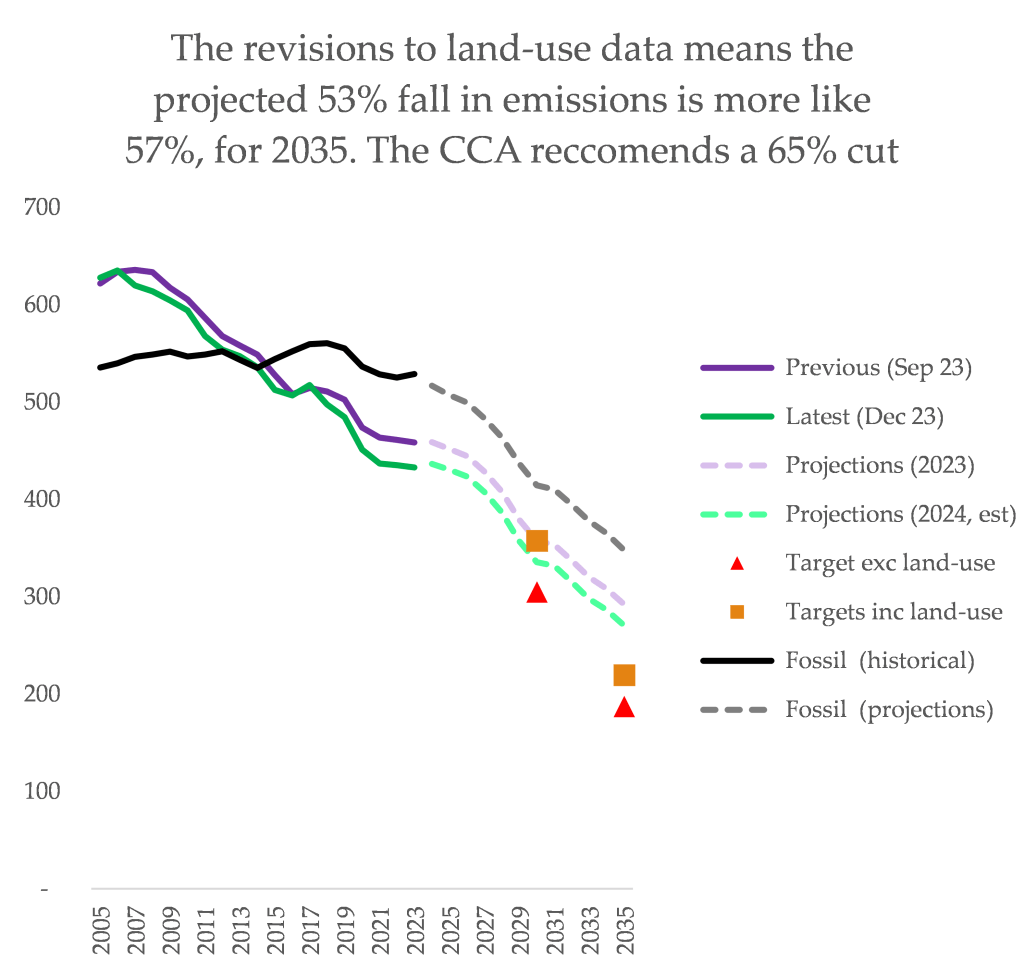

It’s a rough calculation, but I have applied these historical revisions to the projections data. The 2024 projections, due to be published in December this year, will almost certainly look something like this:

The land-use data now has such an extreme effect on masking fossil fuel emissions that the Labor government could fail to achieve its clean power target and fail to reduce transport emissions and still hit the overall emissions reductions target. Land-use data revisions mean no new policies actually need to work, to hit the 2030 targets. The power sector could be 14% below the clean proportion target, and it won’t threaten the economy-wide target.

Okay, I’m sorry. We have racked up a lot of info here. Let me summarise.

- We started with fossil fuel sectors, and saw that a 43% reduction is tough.

- We wrongly added in land-use data, pretending temporary storage of carbon in trees is the same as not emitting. That gets us most of the way to a 43% cut, and all the way when you include Labor’s recent clean power and transport policies.

- We applied the recent revision of land-use data to the future vision in (2), and found that it’s so significant that you don’t even need those extra policies to hit the 43% target.

What a journey. From a wide gulf between stubborn fossil fuel emissions and the target, to a projection that shows Australia will achieve the “ambitious” 2030 goal without lifting an additional finger.

In December, the Department of Environment and the Climate Change Authority will release their assessments and projections and my prediction is that they will absolutely, definitely show that Australia will meet n’ beat its 2030 targets. The role of historical revisions of land-use data will be obscured (maybe mentioned in a footnote) and most of this change will be attributed to policy performance on the part of the government. This will be widely reported and repeated, and most of the people who hear the news will be none the wiser.

This is what climate peace looks like: the continued extraction and burning of fossil fuels on a massive scale, without any disagreement or discontent.

The spirit of Paris

After Dutton announced he was going to ditch the 2030 targets, there was some misleading reporting that that meant a formal exit from the Paris Climate agreement, but it was later clarified that really, reneging on a submitted 2030 target would breach the conventions of the pact, and truly be a genuinely bad geopolitical look.

If it matters so much that Dutton wants to ditch the 2030 target, why does it not matter at all that Labor wants to use a land-use cheat to meet most of it? What is the difference between formally rejecting a target, and subtly rejecting it, when it comes to the hard physical danger of fossil fuels?

The Paris agreement is about putting real blood, sweat and tears into changes that begin the full-scale elimination of fossil fuels from human society, as fast as possible. The Labor party once did this with the renewable energy target, but they are not doing this, today.

If Labor were dedicated to the Paris Agreement, they wouldn’t have weakened their original 45% cut adopted in 2015 to 43%, in 20213. If they were dedicated to it, the targets would be formulated on the real challenge: rapid, deep reductions in the country’s fossil fuel burning sectors, along with agriculture.

Land-use targets would exist, but exist completely separate from other sectors. And of course: the targets would be aligned to an ambitious temperature target as the absolute, most basic first step towards real policies that answer the urgency of the threat.

The Climate Change Authority would be actively calling for a separate target4, and the environment department would do it by default. Climate groups would refuse to engage with the modified, dodgy number and simply rate the government’s performance based on fossil sectors only. As would business, and other political parties and independents.

Soon, Australia will need to set a target for 2035. In December last year, the Climate Change Authority suggested cuts of at least 65% by 2035. They compared this to 2023’s policy-included projections of 53%. The most recent land-use revisions lop a full 4% off the 12% gap. There’s still 8% to go, but hey, what’s the rush? There’s plenty of time.

- If you were *actually* formulating a 2030 target based on fossil-only emissions, it would probably be less than 43% – I am using Labor’s claimed progress here to illustrate what the scale of change looks like based on the figure they promote and brag about. Climate Analytics estimates that a fossil-only 2030 NDC equivalent would be around a 28% cut, and 1.5c aligned would be a 51% cut ↩︎

- Almost every article I read laid the blame for this on communities objecting to transmission lines, wind and solar projects, and not a single one laid the blame at the feet of the government, for failing to introduce stronger clean power incentives or at companies, who won’t act unless it’s profitable enough. Clean energy developers argue all they need is for environmental protection laws to be cut and weakend, and the Labor party is trying, through friendly journalists, to spin the situation as totally fine) ↩︎

- Someone on Bluesky pointed out that the LNP sort of reneged on a climate target too: when they came into power they had agreed to Rudd’s 5% by 2020 target, but that was set with a caveat to increase the 2020 target to 15% if an ambitious global agreement was adopted. I guess it’s technically correct but sort of doesn’t quite feel the same as any one political party walking back their own position! But…point taken, mate ↩︎

- In the 2023 progress report, the CCA does mention the calls for a separate target, but extremely explicitly doesn’t decide to include this as a “recommendation” – merely that “The authority will continue to work on these issues”. Sure you will. ↩︎

Thank you for all your analysis. I have no idea why you are not invited to speak at the Canberra Press Club or in some other forum. The Australia Institute perhaps? So insightful, highlighting the urgency to invest and transition urgently.

LikeLike