Big tech’s selective disclosure masks AI’s real climate impact

Gone are the days when tech companies could choose to share nothing about the environmental and energy impacts of their products. In the wise recognition that it’s now better to drop a narrative they can control than let pesky critics fill the airwaves, major players are dropping curated nuggets of information (sometimes to an audience of journalists unqualified to decode the numbers, unwilling to ask questions, or both).

In June this year, Sam Altman included this snippet in an OpenAI blog post:

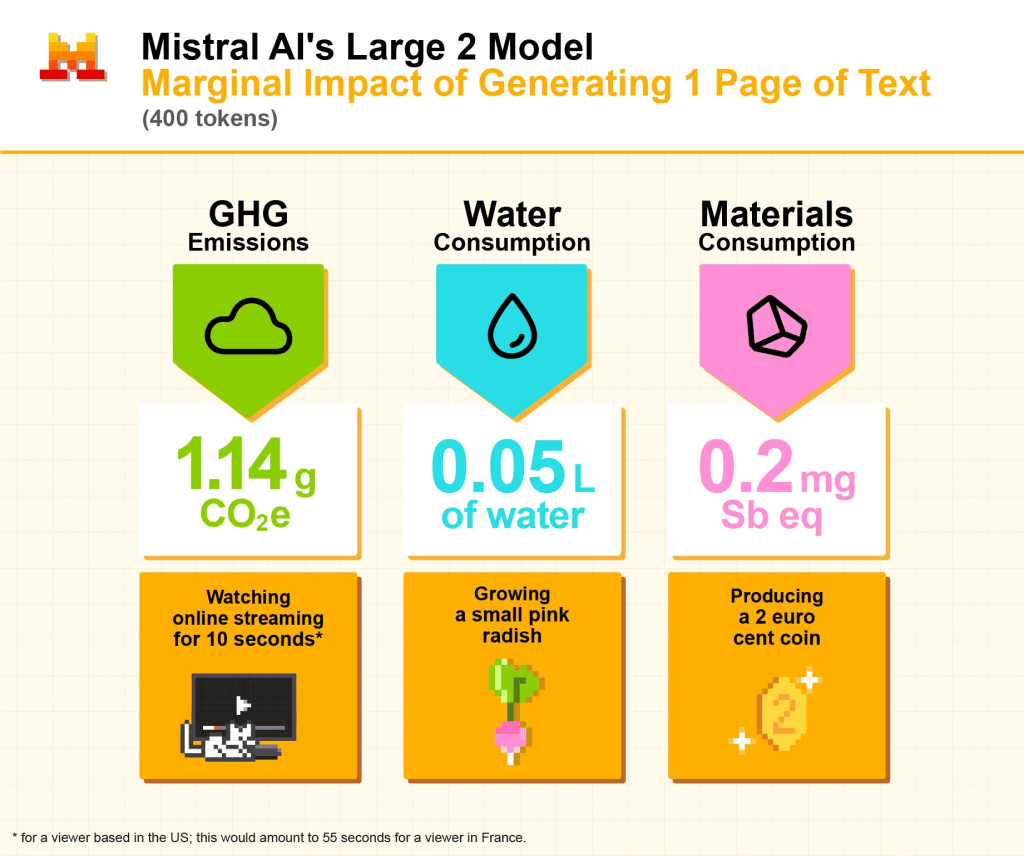

"People are often curious about how much energy a ChatGPT query uses; the average query uses about 0.34 watt-hours, about what an oven would use in a little over one second, or a high-efficiency lightbulb would use in a couple of minutes. It also uses about 0.000085 gallons of water; roughly one fifteenth of a teaspoon"Despite being shared with zero details on how that number came about it was reported widely and it caused a real stir on LinkedIn. A few weeks back, Mistral AI shared a more detailed report, “Our contribution to a global environmental standard for AI”:

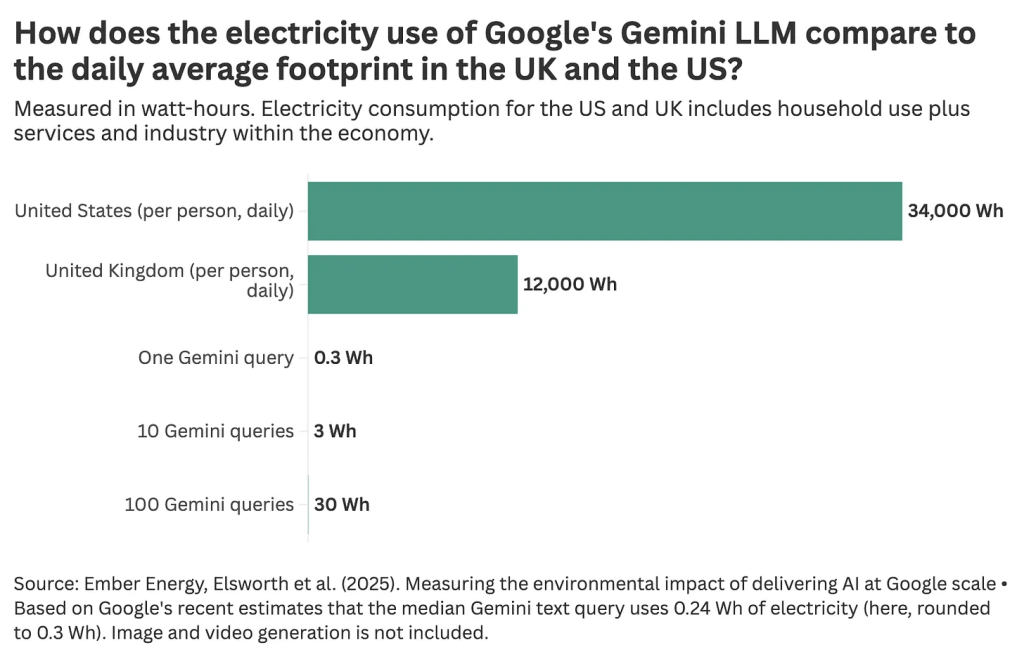

And this week, Google released a major new paper, summarised in this video1:

This is by far the most detail released by a tech company on their own software’s energy consumption2, noting that the baseline we’re working off here was a few months ago ‘literally nothing’, and a few weeks ago ‘Sam Altman said words in a blog’.

A few experts welcomed Google’s report, but cautioned politely that the company might not be painting the full picture. A more common reception has been wise nodding from those who always knew that generative AI was environmentally benign. A nice example is the New York Times’ tech columnist Kevin Roose, who said this:

Ouch. “Vibes-based”. Google know that by presenting a paper that has the aesthetics of peer-reviewed scientific research, it’ll make journalists like Kevin Roose feel like the Smart, Very Serious guy in the room, compared to the loony activists. But it’s not just aesthetics. Let’s dig into how they painted their picture.

The problems with Google’s selective disclosure

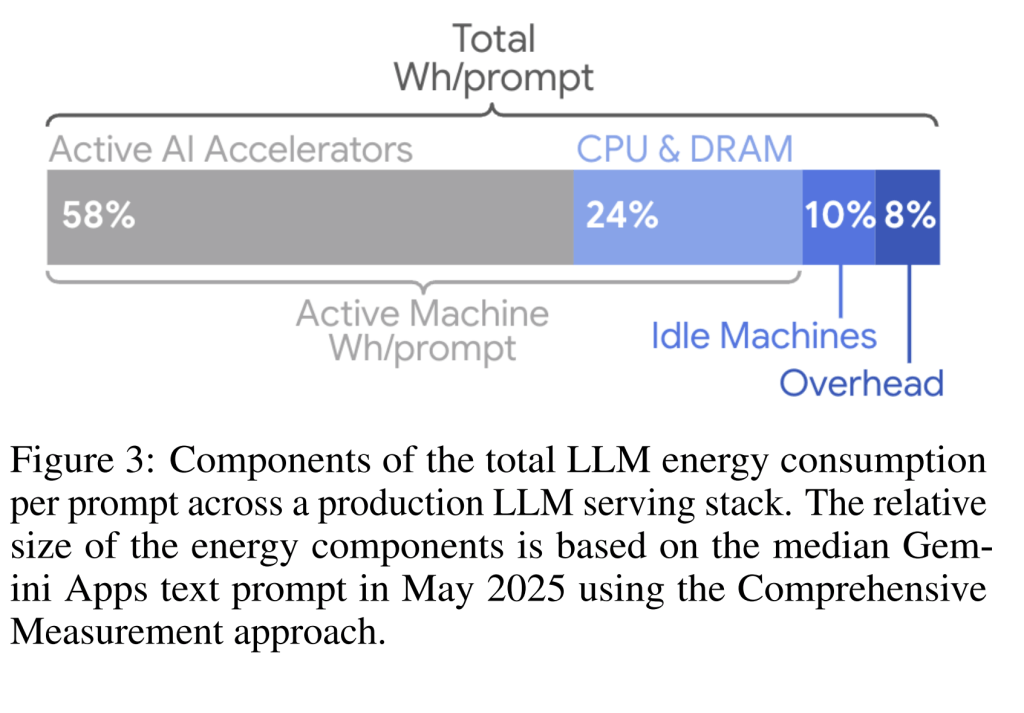

Google sets a clear boundary for what they’re calculating in their full paper, including not just the computer chips processing the query but idling machines and overhead (like cooling or power conversion systems).

What seems like a massive step for transparency and disclosure must be seen in the context of the absence of anything before it. Coming off a baseline of disclosing nothing, the industry can now choose to carefully set the narrative around precisely what they desire and get accolades for doing so.

Lets dig into the problems with what has been presented.

The use of ‘median’ hides the bigger picture

The title of their paper is “Measuring the environmental impact of delivering AI at Google Scale”, but this paper has nothing to do with ‘scale’. It provides an estimate of the impact of one single text query. Not just that, but it provides the impact of the ‘median’ text query: ie, in their total dataset of queries sent to Gemini, they picked the one in the middle. This is how they explain it (the highlight is my own):

"We attempt to define aggregate energy, emissions, and water metrics that are representative of a typical user’s behavior and comparable over time. However, we recognize that this can be difficult with the rapidly evolving landscape of AI model architectures and AI assistant user behavior. We find that the distribution of energy/prompt metrics can be skewed, with the skewed outliers varying significantly over time. Part of this skew is driven by small subsets of prompts served by models with low utilization or with high token counts, which consume a disproportionate amount of energy. In such skewed distributions, the arithmetic mean is highly sensitive to these extreme values, making it an unrepresentative measure of typical user’s impact. In contrast, the median is robust to extreme values and provides a more accurate reflection of a typical prompt’s energy impact. Consequently, we use the daily median as the aggregate value for the metrics defined in Section 3.2 and Section 3.3"Using any sort of statistical summary of the data, rather than the aggregated energy and climate impact across the whole system, will always give a misleading view. They mention their data is skewed, but they don’t mention in which direction. If there is a material number of high-energy ‘reasoning’ prompts skewing their dataset, that means the total energy consumption of all prompts will be very high, with much of the responsibility coming from a few energy-hungry queries.

Part of the reason this is important is that this week, we saw a new research paper that shows that the energy consumption of text generation massively increases for every small gain in accuracy from the use of energy-hungry ‘reasoning’ models:

It would have been pretty easy to supply the range, the skew, the average and the median, or even the actual entire dataset, to avoid any doubt. Any hint of looking at the broader system rather than individual responsibility is excised from this paper. That is clearly an intentional choice: if Google disclosed the system impacts of generation, it would probably look way worse.

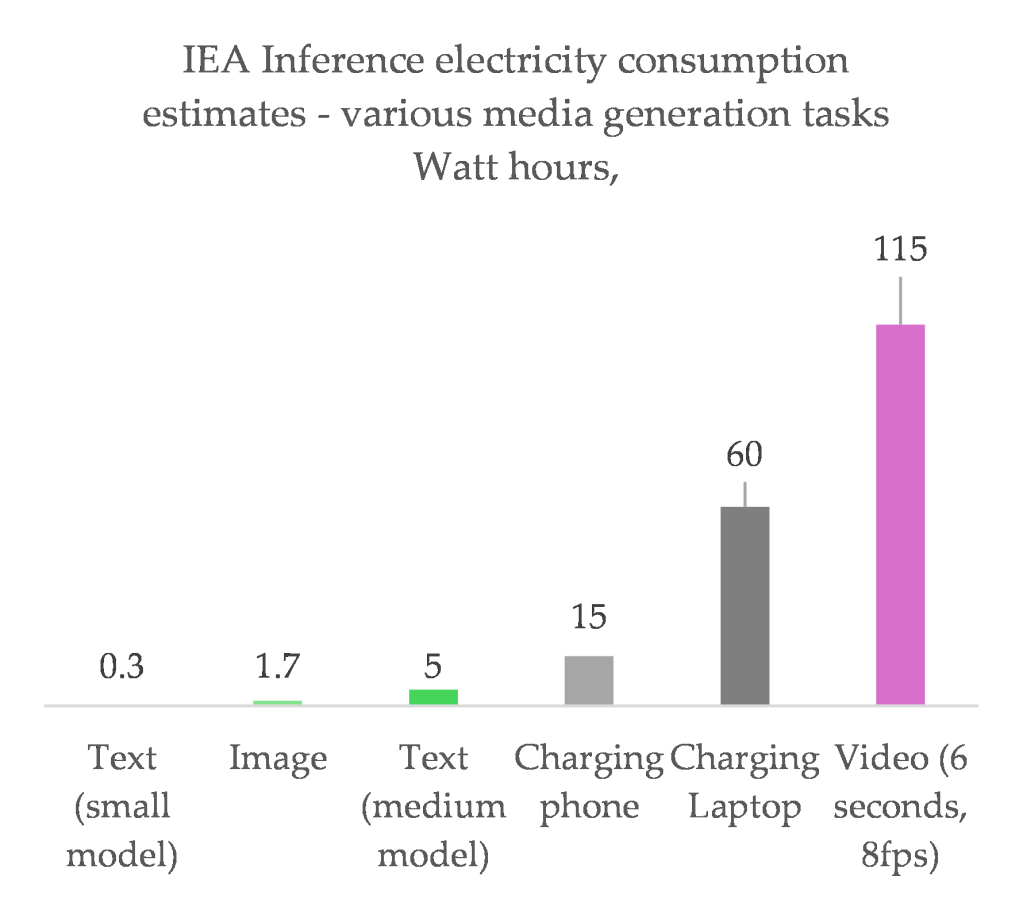

This is only for one type of generative system

Text generation by a chatbot is comfortably the lowest energy form of generative system. In the International Energy Agency (IEA)’s recent report into energy and “AI”, they came up with an estimate of the energy impact of different types of generation that nicely shows the differences:3

Google have been actively trying to encourage the use of video generation. Video slop has become completely unavoidable across social media, particularly on tiktok and Instagram, and it’s clear Google wants to be the one to provide them. While it obviously isn’t going to be the bulk of queries, it’s probably a sizeable chunk of energy consumption, and that’s obviously why they exclude it from their analysis.

Something useful here is that Google have made it clear they’re perfectly capable of determining the very specific energy consumption of generative systems. They could share the same information about images and video, but they choose not to. I think that’s telling enough.

Generative AI isn’t just being ‘used’ – it’s being enforced

I’m willing to bet a big chunk (if not the majority) of queries for text generation happen without any real, clear human intent.

The sheer anxiety with which tech companies have built generative systems into their existing services is mind-blowing. You cannot send a search query in google without it also spammily generating a paragraph of text at the same time; no matter how absurd or inaccurate.

This recent research paper – and accompanying website – explores a wide variety of examples demonstrating how interfaces are designed to bully users into using generative tools.

Tricks like excessive prominence of buttons and toolbars, graphical highlights, interruption through banners and pop-ups and always-on functions that cannot be disabled (or are hard to disable) are design tricks used by companies.

Chatbots are literally presented as magical, and as a multi-purpose tool with no use-case boundaries. They are anthropomorphised as ‘assistants’, there to ‘help’. They are literally everywhere.

The researchers wrote in their paper that:

"In a saturated market, where perspectives of growth are now quite weak, new AI features become very often an opportunity to increase the subscriptions prices of several digital services. We, users, have then to pay the price of the financial risk taken by companies in this AI race. And then more or less visible changes that overwhelmed our interfaces are the direct consequence"This is important: these companies cannot make money unless they actively fabricate use of generative services.

What is the point of telling people of their per-query energy consumption when so much of the broader energy hunger comes from artificially-induced or enforced activation of generative text? And how can Google claim to care about its environmental impact when it pours so much effort into maximising the number of queries whether users want it or not?

How intensity became big tech’s best buddy

Three massive global players in the generative space specifically disclosing nuggets of per-query intensity data within weeks of each other is definitely not a coincidence.

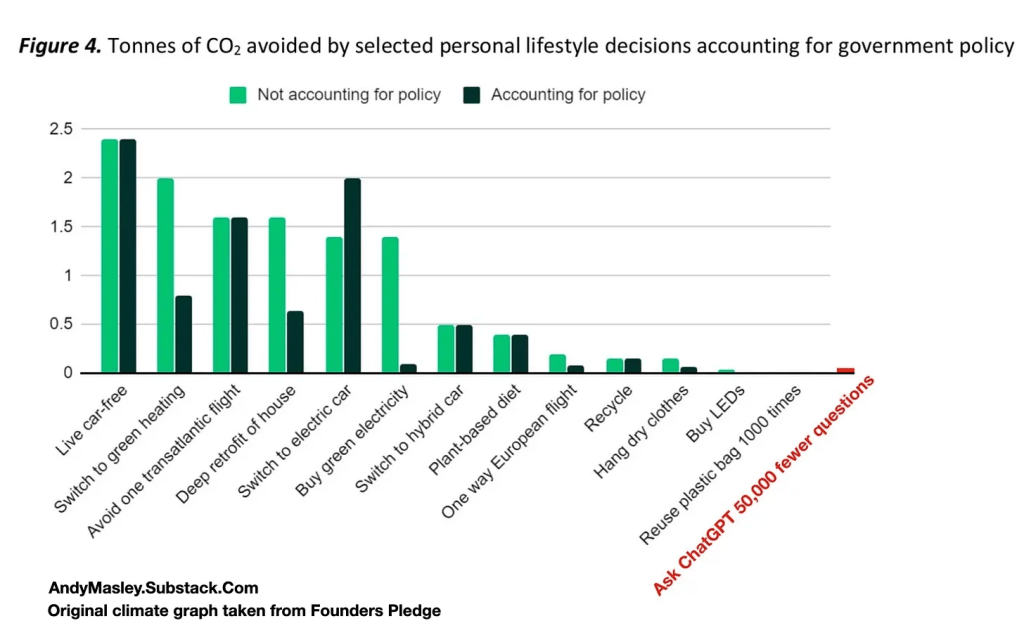

Recently, the head of ‘Effective Altruism DC’, Andy Masley, created and published two very large and very detailed Substack posts4, both presenting the case that ‘using ChatGPT is not bad for the environment‘. I mentioned Masley’s affiliation because it feels important: ‘effective altruism’5 centres around empirical quantification of the impact of a lifestyle choice, and choosing the most impactful of those. You can see how when you look solely at the energy consumption of a text query, Masley easily presents avoiding these queries as having close to zero impact on personal climate action, compared to other options:

Masley uses this to finger-wag climate activists for a catastrophic strategic failure:

"It would be much better for climate activists to spend all their time focused on helping people switch to green heating than encouraging people to hang dry their clothes. If the climate movement should not focus its efforts on getting individual people to hang dry their clothes, it should definitely not focus on convincing people not to use ChatGPT"This is a weird, silly and slightly funny imagining of how the climate movement has been reacting to generative text, images and videos.

Historically the approach of big climate orgs dealing with digital energy consumption has been to encourage tech companies to put money towards funding renewable energy, and it absolutely worked. Many major NGOs are sitting the entire data centre debate out, and you can even find example of NGOs actively using generative systems, or other groups like RMI that focus on technological solutions around flexibility and power. You can also find significantly more critical organisations and campaigns, mostly focusing on community organising around data centre protests or dodgy energy companies trying to exploit the hype to build new fossil fuels.

I have not yet found a single organisation or prominent environmentalist cajoling people for issuing queries to ChatGPT6 (often quite the opposite).

If anything, I am wracked with daily horror at how broadly my colleagues in the climate movement have subscribed to the hype in relying on text generation to replace critical thinking, research and writing. There are also plenty of people within the environment and climate movements who dismiss data centre growth as a hysterical nothingburger.

Our World In Data analyst Hannah Ritchie published a post presenting very similar comparisons, based off Masley’s work, and Ritchie posted an update as soon as Google released their new report, creating a refreshed version of the same narrative:

Part of the reason this comparison is wrong is because it obscures the fact that interactions with generative systems are simply completely new demand, or replace significantly more efficient demand. I’ve seen people use generative systems to create square tiles with plain text on them. That should be compared to the energy cost of writing text in a text box in powerpoint, not to the energy cost of heating food or running huge LCD screens.

Doing a calculation using a chatbot, one of the most-used functions, is several million times more energy intensive than using a calculator and significantly more likely to be flat-out wrong. Doing it using ‘reasoning’ models is more likely to be accurate, but tens of millions of times more energy intensive. It’s the single worst form of tech-executive-anxiety-induced digital bloat that has ever occurred.

As I wrote here, this is analogous to how the car industry created a situation of ever-worsening car bloat to maximise their profits, or how plastics producers fabricated their own necessity through single-use food packaging. Personal responsibility of use is part of this story, but it’s a small part, and that’s why the climate movement doesn’t hyperfocus on it for ChatGPT, SUVs or single-use plastics. They are focused on systemic issues and corporations.

It’s worth noting here that boycotting generative systems (like I do) is still a meaningful and important thing to do, and encourage others to do7. If you are doing it because you want to save grams of carbon dioxide like coins in a piggybank, it’s not going to be earth-shatteringly effective. I don’t think that’s why most people do it – I think most people do it because it makes them queasy to actively help juice the stats of an industry demonstrating its gross lack of ethics in a shocking number of ways.

I think it’s likely these Substack posts influenced thinking within companies trying to figure out how to control the public narrative around their impacts. Anthropic even specifically provided Andy Masley’s Substack post when pressed to share more information about their energy consumption.

By foregrounding per-query impact, substack writers and companies are erasing the real problem with generative systems: they are oversold and overused, in an anxious bid to make impossibly high hopes come true, even if that’s artificial rather than organic (in terms of diversion away from real action, it is the weird flipped cousin of the way fossil fuel companies exploited and popularised ‘carbon footprint‘ messaging to divert responsibility for action away from themselves).

The generative industry is environmentally harmful

At the Google level:

If the broader narrative of near-zero energy and environmental impact from generative systems were true, you would expect the overall figures reported by the company to reflect a shrinking environmental and energy footprint.

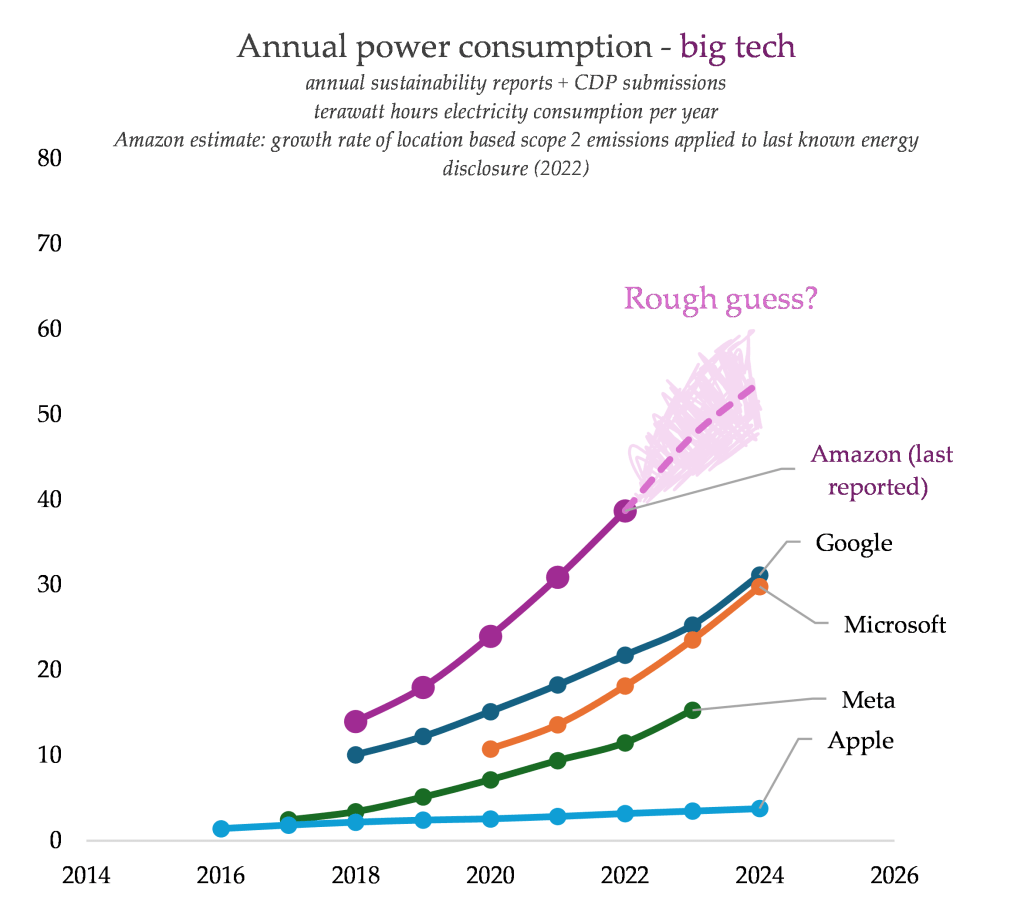

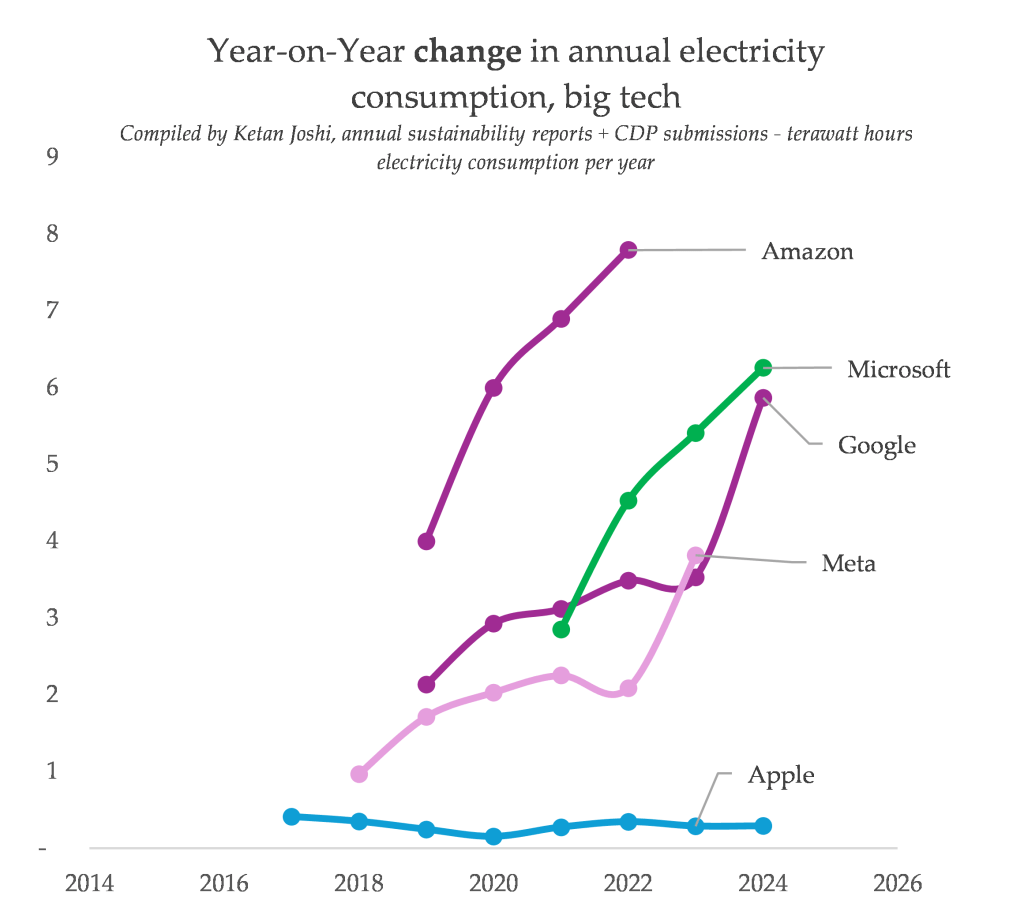

As you probably guessed, or maybe knew already, Google, like Microsoft and Meta, has blown wildly past its climate targets thanks to a combination of skyrocketing direct energy consumption and the climate impact of speed-building new data centres. The two images below, from my compilation of big tech energy disclosures, show two different things.

First is the rising total energy consumption, by company. The second shows the year-on-year change in consumption. Google’s growth was already accelerating, but between 2023 and 2024, the rate of growth doubled. If this isn’t the impact of the company’s new generative tools, then what the hell is it?

A single person querying a chatbot isn’t as energy intensive as heating food, or moving in a car. But the broader implementation of generative systems (text-spam ‘reasoning’, images, videos, enforced demand through design tricks etc) is energy hungry in aggregate, and it’s getting worse every day.

Look at Google’s rising total energy consumption. Can you see why these companies have been so profoundly thrilled to adopt the per-query narrative frame, when it comes to climate and energy impacts?

At the industry level:

Environmental impacts from “AI” are often derided as being based off improbable forecasts of the future. But you can find any number of material, real and immediate impacts from the data centre boom happening right now. This is tactile stuff, and again, not what you would expect if these companies were delivering inert, energy-efficient services that ‘don’t harm the environment’.

Existing digital services (like video streaming, file storage, video calls and gaming) have all come under scrutiny in terms of their physical infrastructure and energy costs, but none of them have caused such an intense upward swing in the numbers.

A nice example of the uniqueness of generative software is Elon Musk’s absurdly oversized ‘Colossus’ data centre project, which came with a massive fleet of fossil-fuelled turbines. This entire facility exists purely to train and run X’s viciously racist, climate-denying chatbot, which pours hundreds of randomly generated falsehoods into the heads of millions of low-information dudes every second.

Try and name another social media website that included a feature that requires its own fossil fuelled data centre. This is truly a completely new type of ultra-bloated digital infrastructure, far closer to brute-force bitcoin mining than to video streaming or gaming.

You could easily generate a Substack post highlighting how a single Grok query is a tiny fraction of your daily energy diet, but it would be no consolation to the communities of colour that are choking on this feature’s fumes.

It’s the same story for Meta, which is building three entire gas-fired power plants to supply electrical energy for a massive new data centre in Louisiana. Oracle just announced 1.4 gigawatts of 100% fossil-fuelled data centre capacity. An Irish data centre operator argued that “having gas as the primary fuel of the power plants played its part in decarbonising the national grid”. In Texas, a massive fossil gas boom is being driven by the growth of data centres, resulting in an emissions impact of about 30 new coal-fired power stations worth of greenhouse gases. Crusoe, a company that until recently was all in on Bitcoin mining, has now turned to figuring out how fossil fuels can power “AI” data centres:

A community in Virginia recently defeated plans for 3.5 gigawatt fossil gas power station dedicated to fuelling a new data centre. By my calculations, it would’ve been the second largest gas power plant in America, had it gone ahead. The International Energy Agency recently wrote that

"The state of Virginia8 is now estimating that 9.9 GW to 15.3 GW of new fossil power would be needed by 2040 even if the Virginia Clean Energy Act was met in full given the concentration of DC load growth in exempted co-op territories.....the AI-led [data centre] spending spree may also be ushering in a new wave of fossil-fired generation in advanced economies, the United States in particular".

And at the country level:

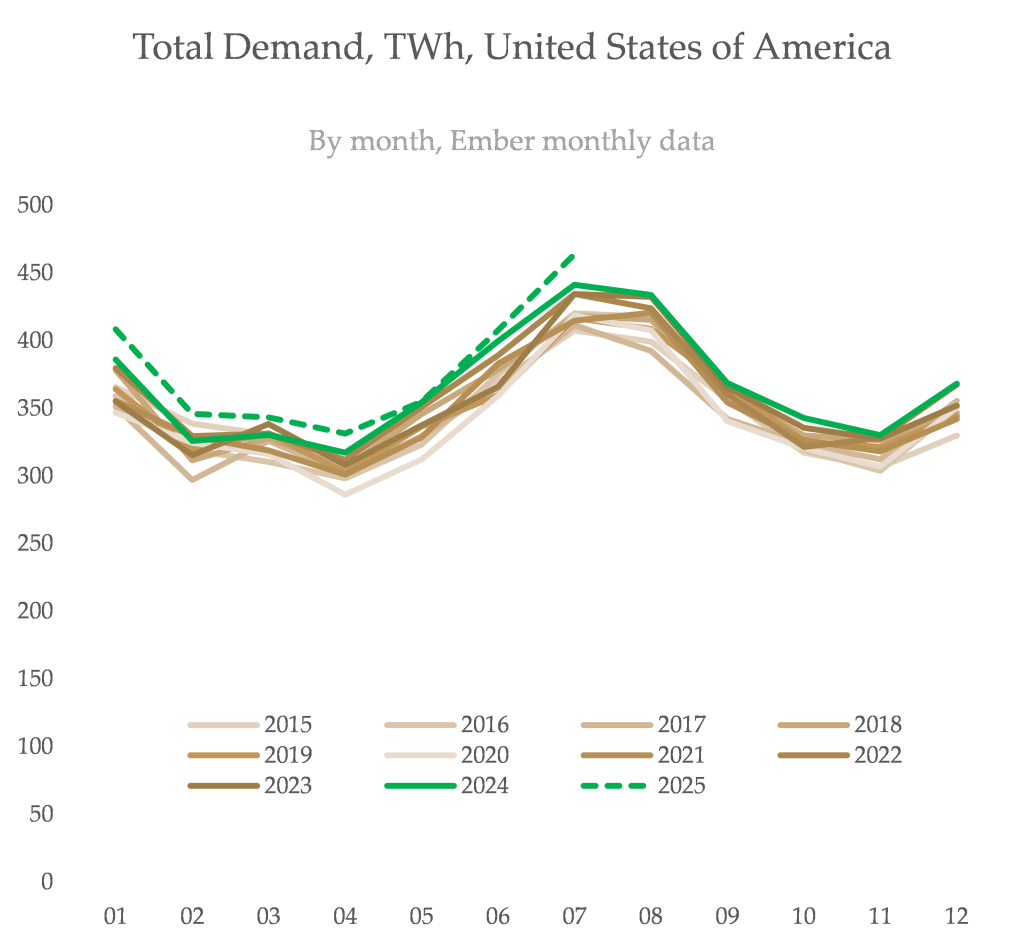

Most data centre growth in the world has been concentrated in America, and most data centre growth relates specifically to the types of hardware used to power generative text, images and video. And most of America’s growth in power demand relates to data centres.

America’s rising power demand has resulted in the country’s coal and gas power stations persisting rather than falling, thanks to all the new renewable energy being diverted to meet new demand instead.

For the past 16 months, power demand in the US has been at a record high (for that same month every year prior). 2025’s peak emissions were higher than the peaks of the past four years. This is systemic, not seasonal: America’s data centre soaked grid has begun properly backsliding.

I have seen many, many instances of data centre growth being dismissed on the grounds that it’s a small-sounding percentage of total global growth of all energy used by the human species (with the caveat that there may be concentrated local effects). It is pretty remarkable how often I see this entire issue dismissed because the percentages are single digits, and when I ask at what percentage data centres would be considered a problem, I never, ever get an answer (let alone a clear one).

In America, data centre growth is clearly playing a major role in the dynamics of coal and gas generation. It is a massive proportion of demand growth, and bears much of the responsibility for rising coal and gas output on the grid (before we even consider the new gas plants being panic-built en masse on top of historically disenfranchised communities).

If the same growth manifests as strongly in other parts of the world, it’ll have the same immediate, quantifiable effect. It is true data centres are a local issue, with problems of air pollution, land grabs and rapidly rising electricity bills due to grid congestion. But their sheer size and scale is resulting in clearly detectable state and country level impacts, where the carpet bombing has been worst.

Conclusion

It is misleading to present a single chatbot query as if it’s the final answer on the industry’s energy, climate and water impact.

Doing so leaves out the different types of queries: ultra-long ‘reasoning’ text, images and videos. It obscures whether queries are consciously requested, enforced or induced using sleazy interface design tricks. The companies that run so much of the world’s digital infrastructure are mandating overconsumption like a water supply authority installing thousands of open taps to juice their water delivery numbers.

It obscures the sheer volume of queries being sent. It obscures the fact that this is either entirely new energy demand or it replaces a more efficient method (see: calculators).

It deflates the politically powerful act of boycotting a harmful industry into sloppy individualistic math. It has been done in a way that actively helps the industry so profoundly that the biggest companies have become foster parents for reassuring carbon footprint talking points.

The per-query narrative framing paints the precise opposite picture to what we see when we look at what really matters for environment and climate: the absolute figures.

Regions with high data centre concentration are seeing accelerated growth in power demand that incentivises fossil fuels, either slowing down climate progress or reversing it entirely. The sphere of that influence is expanding from towns, to states, to countries. The companies that own them can only partially hide the steep backsliding in their aggregate disclosures.

Renewable energy that should be displacing fossil fuels ends up meeting new data centre demand, granting coal and gas extra years and decades of immediate, measurable harm to human life. The worst players don’t even bother with the grid, plugging data centres directly into new, custom-built fossil fuelled power stations that’ll hurt people for decades after the hype dissipates.

Tech companies have recognised how they need to evolve control of the public narrative around the products they provide, and so they’re successfully shifting the conversation towards consumer responsibility.

It is depressing how well it works, but remember that none of this is inevitable. The first step is rejecting the framing that’s now being breezily adopted by an industry that puts all of its energy into sounding good, rather than doing good.

- It’s worth mentioning that Google has a collection of ‘power purchase agreement’ deals with renewable energy facilities to claim the power they generate as their own, on the grounds that their funding brought it into existence. You can take that or leave it, but that alone fundamentally changes the company’s reported emissions by a massive amount. Google are using market-based data in their paper. That isn’t great and they should’ve shared both, but to be honest, the emissions number would sound small if they used the location estimate instead (and it’s odd they didn’t). The main trick still lies with the fundamental problem around only sharing the intensity of their product’s climate impact, not its absolute impact. ↩︎

- There is a whole debate here around water consumption, but it’s one I’m wildly unqualified to even slightly comment on, so I’m going to focus on my area of expertise, which is electricity, energy and climate impacts. Go and read Shaolei Ren’s response to Google’s paper here! ↩︎

- It’s notable that the video they generate is 6 seconds long and 8 frames per second, whereas the videos being made with Google’s systems right now would be many, many times longer and at a higher framerate (and include audio) ↩︎

- So, um, I tried to demonstrate that you can make broadly socially damaging activity look small by presenting it as the numerator of a bigger denominator in this post, and Masley somehow took that to mean that I was trying to say that ChatGPT’s energy proportion is high, or that SUVs are fine? To be fair I didn’t write out my point explicitly or simply enough, so here it is: you can’t get a good read on the broad environmental impact of a system by seeing what percentage of your total daily energy or emissions impact it is. This why it’s so easy to make something terrible (like SUVs) look relatively acceptable, just by being selective with numerators and denominators. Plenty of obviously bad things can be made to look reasonable: I don’t think the energy consumption of a single query is actually a large proportion of individual daily use, I just think that it’s wildly insufficient when assessing whether the growth of a weirdly energy intensive service is good or bad for the climate. I think it struck a nerve because the longermist / effective altruist community default to this sort of ‘efficiency metric’ when asking these questions, without thinking much about how seriously misleading this presentation can be. ↩︎

- It’s worth noting that William MacAskill, ‘one of the originators of the effective altruism movement’, recently shared an example of his interactions with Google’s Gemini large language model: “Sometimes, when an LLM has done a particularly good job, I give it a reward: I say it can write whatever it wants (including asking me to write whatever prompts it wants).

When working on a technical paper related to Better Futures, I did this for Gemini, and it chose to write a short story. I found it pretty moving, and asked if I could publish it. Here it is” ↩︎ - Yes, there is a good-sized contingent of folks (particularly on my beloved Bluesky) who’ll cajole someone for using ChatGPT based on the environmental impact of doing so. But this is not the organised strategy of the climate movement, ↩︎

- This is a really good piece on how it’s good to shame AI boosters – not so much individual users but the corporations and systems that try to design its excess deployment at great cost to the rest of us. ↩︎

- Also see my recent post on Texas ↩︎

This is highly informative and necessary, thank you for this !

May this awarness come to the general public

LikeLike

I’m Andy Masley (mentioned a few times) and disagree pretty strongly with the framing that trying to answer the “Are individual AI prompts bad for the environment” question individualizes the problem too much. I included my reply to that in this post for anyone interested.

LikeLiked by 1 person