David Attenborough’s good film and the bad past it’s haunted by

David Attenborough’s new film, ‘A life on our planet’, is pretty good, and well worth your time. It’s well produced, heartfelt and interesting. It is a moment of pause, reflection and seriousness from one of the most significant naturalists of our time, and you shouldn’t miss it.

It is a rich depiction of what we face losing without immediate action, and generally, it does a very good job of presenting pathways of action that are inspiring and accessible. But it leaves out a few important things that we ought to consider, in addition to skipping over some problematic history under some of its ideas.

What is clear, now, is that climate action requires considerations of justice and equity. Not just in shutting down fossil fuels, but in creating solutions that are fair, so as not to recreate the wrongdoings of the past. There is little of this, in the film, and it’s worth exploring why.

The hazards of averaging

The film opens with a series of beautiful long shots of the land near Chernobyl; deserted after the nuclear disaster that killed many and resulted in the abandonment of the nearby town. Attenborough specifically places blame on ‘human error’ for the disaster.

From the outset, I couldn’t help but feel a twinge of concern about this. Chernobyl was, of course, not intentional. But the mistakes came about as a consequence of deeper systemic problems in the management and the political structures around the machine.

This was depicted nicely in HBO’s indulgent but important mini-series, in which deep cultural problems around lying, denial and deference to power structures lead to the disaster, and the disastrous, insufficient post-accident response. It is perfectly analogous to a vast array of related environmental issues, like climate change, but that is sadly missed in this film’s opening.

Much of the film centres on the natural world, along with a few key threats to it, such as industrial-scale fishing and whaling. The only significant time spent on deeper ’causes’ of problems comes when the film begins to address human population growth.

It is a long-held focus for Attenborough. He did not come to accept anthropogenic global heating until hearing a lecture in 2006. Attenborough said the lecturer “showed a series of graphs showing world temperature and, critically, population as well as ingredients within the atmosphere. The congruence of those things convinced me beyond any doubt whatever that not only was the climate changing, but that humanity was responsible for that”. It was population that brought him to climate.

Throughout the film, a ‘ticker’ updates us as we travel through the past, first with human population, then emissions, then wilderness loss:

Midway through the film, one of Attenborough’s two emotional moments comes when he talks about human domination over Earth:

Later, Attenborough proposes a solution to the excess of human presence. “On current projections there will be 11 billion on earth by 2100. But it’s possible to slow, even stop population growth, well before it reaches that point”. They cite Japan’s frozen population growth (a good example of the insufficiency of this approach, as Japan remains badly off target for climate action, and biodiversity impacts continue unabated).

“As nations develop everywhere, people choose to have fewer children. By working hard to raise people out of poverty, giving all access to healthcare and enabling girls in particular to stay in school as long as possible, we can make it peak sooner and at a lower level”, Attenborough says.

This is a significant and welcome softening of previous positions on population growth, many of which involved using policy and force to cull human life, and often, specific human life from non-white countries.

In 2013, Attenborough suggested withholding aid to those suffering famine in Ethiopia because aid didn’t address population growth. He also specifically targets regions in the Global South. “When you talk about world population, the areas we’re talking about are Africa and Asia, you know”, he said. This xenophobic skew isn’t repeated in the film, but controversy did arise when the UK arm of charity WWF cut their own trailer, illustrating excess population with a crowd of bathing brown people, and illustrating the ‘better’ world with a single European cycling on the street:

After a backlash, WWF removed the video and apologised. The racist visual language the agency default to out of pure instinct harks back to a white supremacist history which I explore further below. This movement ‘averages’ humanity into two groups: those in the Global South ‘breeding’ too wildly, and white families in the Global North, who are at one with the natural world, and enjoy hiking and four wheel drive tours.

The film itself isn’t as ham-fisted in its imagery, but most significantly, it fails to acknowledge the ugly past of population control. That is a problem that is hard to look past, because it illustrates how a recognition of past injustice – like white supremacy, colonialism and racism – needs to be baked into our visions of the future. Without a deep, honest reckoning like that, the chances of things going wrong again are very high.

How the next film could be better

The major risk of downplaying the role of climate justice is that even the good solutions can become terrible if social and political problems aren’t fixed. Renewable energy, for instance, is mostly good, but not inherently good. It can be built in a fair and democratised way, or a non-democratic and environmentally damaging way. Mass tree-planting can have awful environmental and human outcomes, but it can be great if it’s done right. Perverse incentives like profit motives both create the problem and taint the solutions.

Better futures are not tuned along the single axis of population, despite what the ‘ticker’ might tell you. They are tuned to how effectively we counter the root cause of the current problems, including injustice, corruption and corporatism.

“All our environmental problems become easier to solve with fewer people, and harder — and ultimately impossible — to solve with ever more people”, said Attenborough, a few years back. It’s demonstrably untrue. It only takes a handful of politicians, executives and lobbyists to trap the rest of us into a pathway of self-destruction, one molecule of greenhouse gas at a time.

The film ends with even more beautiful, long shots of animals roaming in the forest-filled overgrown bones of the abandoned neighbour city to the Chernobyl plant, Pripyat. That disaster came about because incredible technological power failed in the context of broken human relationships between science, technology, power and politics. If Ukraine’s population were half, would the safety problems of that plant have been avoided? Obviously not.

The atomic catastrophe also immediately and permanently stunted the growth of nuclear power, once thought to be the key solution to the fossil fuel problem. It is the shape of human life, not the mere presence of human life, that causes environmental damage. The same risks that broke nuclear could break all the potential solutions at our disposal for climate, today.

Modern climate action centres so intensely on justice because no climate solution will work without the curing of pre-existing harms. Environmental action without this focus will either fail totally, or stumble into an ugly half-success that creates new problems as it goes.

In the final monologue of the film comes Attenborough’s other emotional moment; in which he highlights this is about saving us, not nature, and that we have what it takes to quickly convert humanity into a sustainable species. This is his most important message – that humanity can be saved, and that with will, focus and determination, we can learn to thrive without setting a deadline for our extinction. It is a welcome and meaningful departure from the misanthropic tropes of the population movements of previous decades.

Attenborough presents this film as his ‘witness statement’ – his final message to the world. I really hope it’s not true. I hope he has the time and space to make another film with the same spirit of action and urgency, but with plenty more time spent on the best thinking about the role of justice in climate solutions.

For some extra reading, I’ve written about the history of why population control has such deep ties to racist movements, below.

The history of population control

The idea that human presence is toxic is a simple antithesis of climate justice. It supposes that we, as creatures, cannot be saved. We are unfixable, and our presence is poison. Even in a just world, we’d be just as toxic, because there is no change to humanity – technological, social or political – that could cure our bodies of their lethal virulence.

The math is relatively simple: each human has an environmental impact. The more humans, the worse the impact. This was the core thesis of truly bad film released earlier this year, ‘Planet of the Humans’, in which its director Jeff Gibbs and Executive Producer Michael Moore outlined a misanthropic and error-riddled thesis framing humans as ‘cockroaches‘. Like the team that created that film, along with every invited ‘expert’ in the final product, this worldview stems almost solely from wealthy, white origins.

This is an important caveat. Those expressing concerns about population don’t include themselves in the wishlist of deletion. This is about other people. “Fretting about overpopulation is a perfectly guilt-free–indeed sanctimonious–way for ‘progressives’ to be racists”, wrote PJ O’Rourke, in an essay titled “Just enough of me, way too much of you”.

One of ‘the most influential books of the 20th century’, ‘The population bomb‘ (1968), by Paul Ehrlich, argued that human population was so great that widespread starvation was at the door. The book literally begins with the following incredible paragraph that I can only include in full:

“I have understood the population explosion intellectually for a long time. I came to understand it emotionally one stinking hot night in Delhi a few years ago. My wife and daughter and I were returning to our hotel in an ancient taxi. The seats were hopping with fleas. The only functional gear was third. As we crawled through the city, we entered a crowded slum area.

The temperature was well over 100, and the air was a haze of dust and smoke. The streets seemed alive with people. People eating, people washing, people sleeping. People visiting, arguing, and screaming. People thrusting their hands through the taxi window, begging. ‘People defecating and urinating. People clinging to buses. People herding animals. People, people, people, people.

As we moved slowly through the mob, hand horn squawking, the dust, noise, heat, and cooking fires gave the scene a hellish aspect. Would we ever get to our hotel? All three of us were, frankly, frightened”

Paul Ehrlich, The Population Bomb

The dripping disgust in these words is familiar to me. I’ve recognised it every time someone on Twitter has called me ‘street shitter’, or told me to go back to the disease-infested country I came from. It sets the scene for a movement that aims squarely at the regions of the world where population is growing fastest – Asia and Africa:

It is naturally no surprise that this movement has drawn in racists looking for reasonable-sounding justifications for their deeply felt disgust at non-white people, and created new racists who follow the worldview through to its logical conclusions.

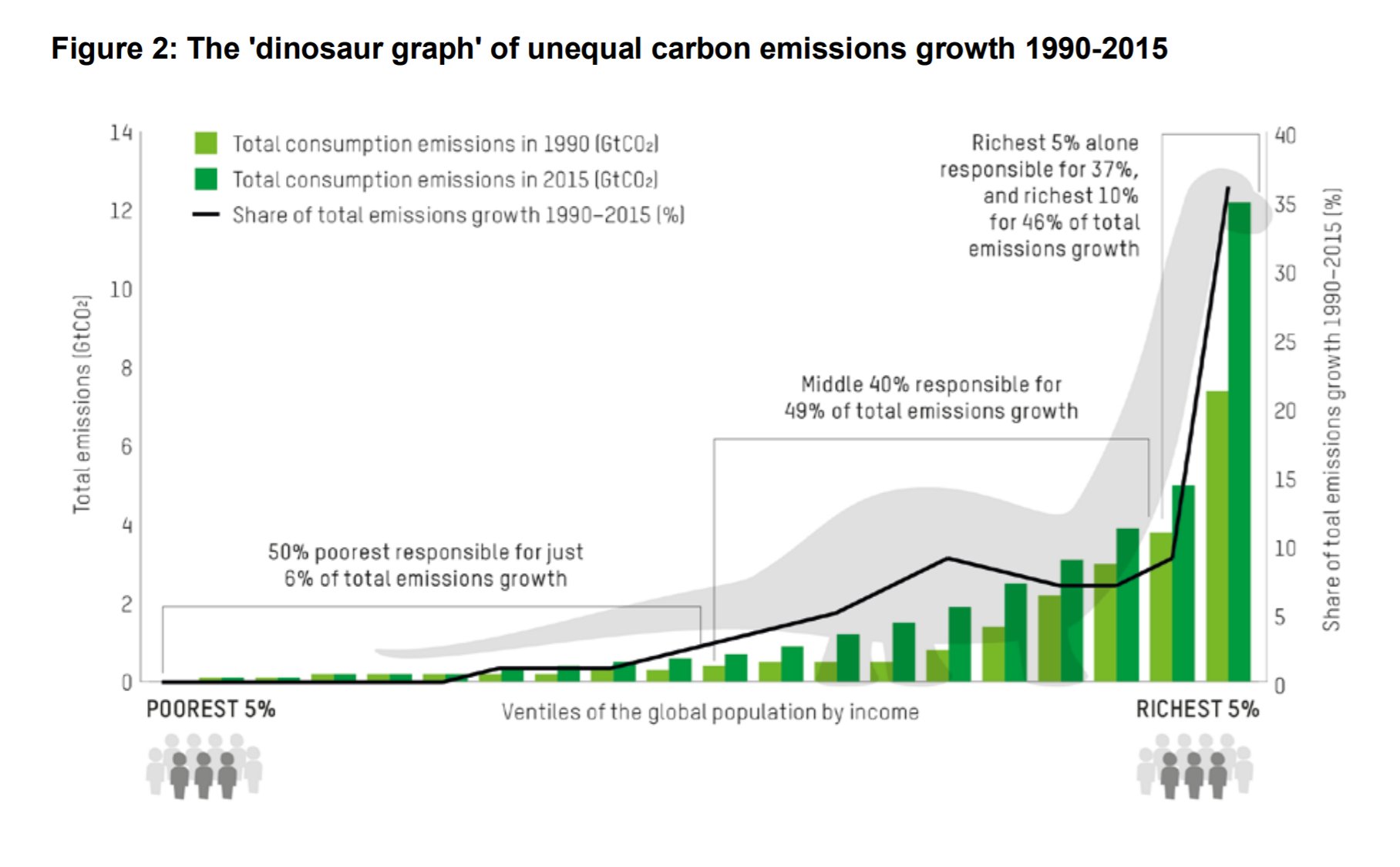

Without going into too much detail (there’s plenty here), it’s clear that population growth is slowing, and will level off by the end of the century. The far better pathway to tackling the problems of environmental damage and climate harm are dealing with injustice, as the cause of this problem is unevenly distributed across wealth and power.

This is why population control is the antithesis of climate justice. It very specifically erases the distinctions, ‘averaging’ humanity into a single, uniform virus infecting the planet.

The desire to reduce human life – specifically those non-white disease-ridden brown bodies charged with breeding too wildly – has been a conduit of cruelty from within the environmental and climate movements for decades. It is still happening.

Population control is still letting racism seep into climate action

In 2018, Blythe Pepino, a young, frustrated and talented millenial yearning to do something for climate action started the ‘Birthstrike‘ movement, designed to provide support, networks and safe discussions for parents deciding not to have children until climate action is taken seriously. This was very explicitly dissociated from population control movements. “Even with drastic, draconian, eugenic policies of population reduction – which are completely immoral, we wouldn’t save ourselves. We have to change the way we live”, Pepino told The Guardian. “It is in a sense a very hopeful act. We’re not just making this decision, hiding it and giving it up. We’re politicising that decision – and hoping that will give us the chance to change our minds.”

Fast word to a month ago, and Pepino and her co-founder have had to shut down the entire movement, specifically citing the influence of overpopulation activists as the reason:

“We have to concede that we underestimated the power of ‘overpopulation’ as a growing form of climate breakdown denial – even in some of our most revered scientists and fellow climate activists.

Founders of the Birthstrike movement

It is tragic and infuriating that such an important movement cannot exist without being immediately poisoned. There is no ambiguity in the words of the founders of this movement. “In order to achieve system change ‘justice’ must be front and centre”.

Modern population movements have deep roots in modern environmental movements. In Australia, the ‘Sustainable Population’ group cites renowned climate activist Tim Flannery as a ‘patron’; they are explicit about significantly reducing migration as part of their advocacy. An article shared several thousand times across Australia’s climate and environmental groups proposed “net zero migration” as a climate solution, even as the prospect of climate refugees from worsening disasters increases. This is a more severe immigration policy than Australia’s most racist political party, One Nation, but the inclusion of this went entirely unremarked.

Ditto for the UK’s ‘Population Matters’ – heavyweights David Attenborough and Jane Goodall (you might have seen her on British Airways ads) are patrons, as menionted above. In 2015, Population Matters argued that Britain ought to stop accepting refugees from Syria because Britain’s population was already too high. Around the same time, the group offered paid carbon offsets (normally things like planting trees and building renewables) that went towards attempts to reduce population.

Framed in language of ’empowerment’ and the ‘right to choose’, charity that expects a very specific reproductive outcome goes as badly wrong as you might expect. The real world manifestation of these policies can be tragic.