Netflix does not have a great climate plan

There is a telling bit in the first episode of the most recent season of Charlie Brooker’s ‘Black Mirror’.

The episode opens with a staff member from fictional streaming service ‘Streamberry’ (designed as obvious in-show analogue to Netflix) presenting a new audio compression algorithm that’ll make their service far more efficient, delivering the same service with fewer ‘data servers’ and therefore a lower climate impact. Her boss Joan (played by the great Annie Murphy) turns it down, citing hesitation from the board.

Netflix is clearly making fun of its critics more than it is making fun of itself, here. I couldn’t help but instinctively agree with it: the finger-wagging crap that has been directed at millenials watching too much streaming content has been infuriating, and often based on wild exaggerations. No matter the assumptions, we are far better off watching a TV show on the couch than doing a boomer style international cruise, for our leisure activities.

Generational spat aside, Netflix absolutely see themselves as a genuine industry leader, when it comes to climate. They brag about commissioning shows and movies they see as promoting climate-aware messages, such as 2021’s ‘Don’t Look Up’, or this year’s ‘Blue Planet 2’. They also heavily promote their actions to reduce emissions, along with their sustainability plans and achievements, across their social media and website.

In short: they don’t think they’re a sinister corporation that fires young staff coming up with emissions reductions tools. ‘Streamberry’ is what Netflix thinks its harshest critics think Netflix is.

Here’s the thing: Netflix are the caricature. They aren’t engaging in deep, real emissions reductions. They aren’t setting good targets. They’re using greenwashing tactics and, most significantly of all, they’re rapidly expanding their energy hunger under the guise of responsible climate action.

Netflix’s bad power accounting

If Netflix are using some amazing algorithm to compress their shows, it doesn’t show. Their power consumption has been growing steadily, as their user base grows and efficiency gains at data centres start materially slowing down:

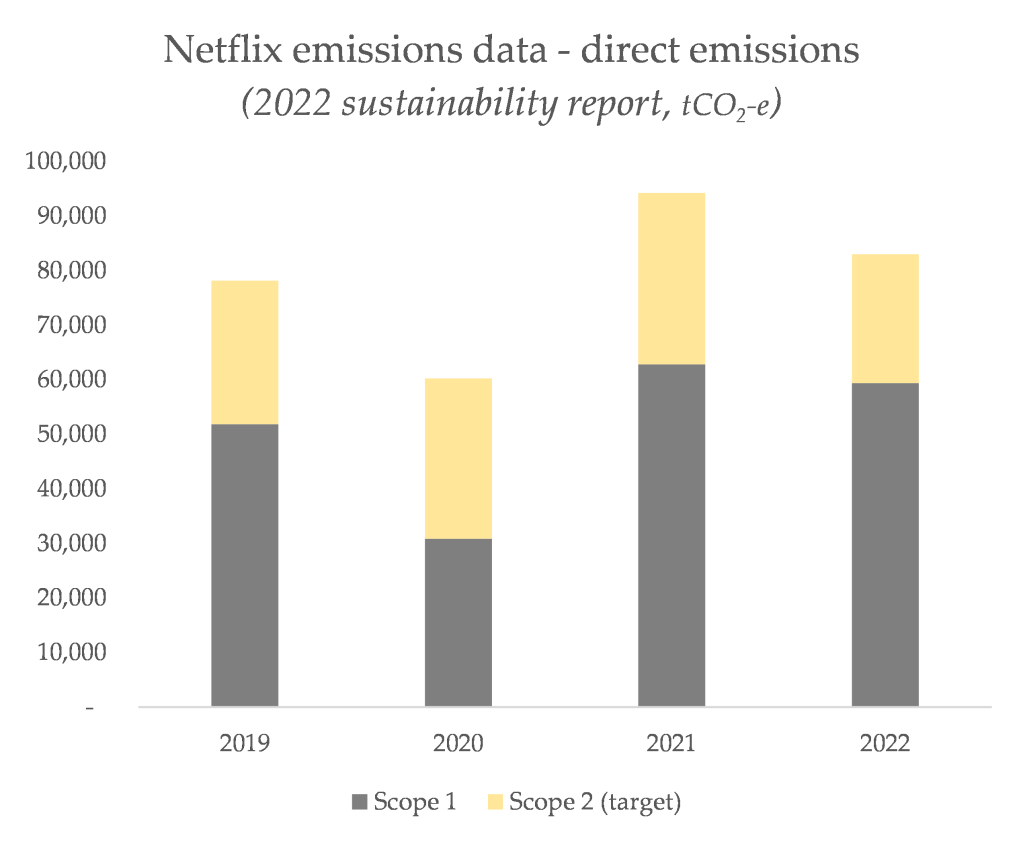

This is from Netflix’s 2022 sustainability report. Let’s talk about their ‘direct’ emissions first – the emissions they own as a company.

About half of their direct emissions cover the in-house production of shows and the next big chunk is corporate emissions (like offices and business travel). Only about 5% of what they report is from the actual streaming process.

Direct emissions have fluctuated significantly, with 2022’s final measures being slightly higher than 2019. The pandemic shifted productions out of 2020 and into 2021, resulting in this weird see-saw, but ultimately, a rising trend:

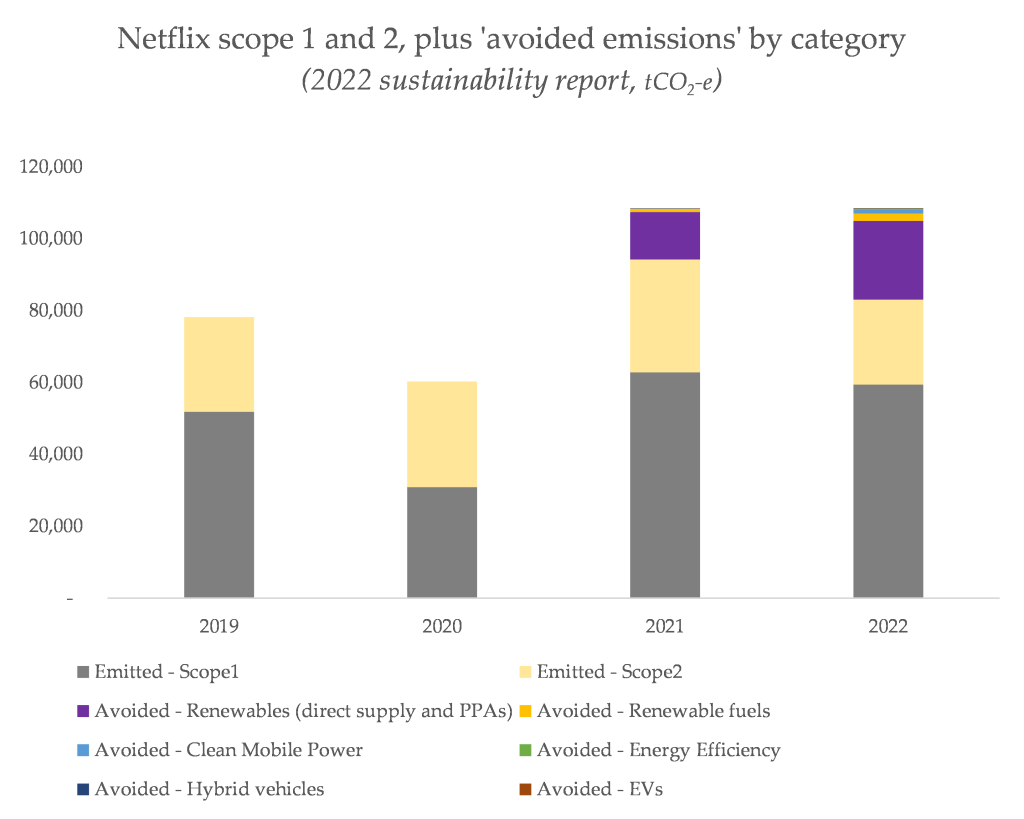

It’s a slight rise on 2019 emissions, the company’s baseline, but Netflix lists all the activities they have taken to avoid an even higher increase, through a table of “avoided emissions” activities:

Most of the ‘avoided emissions’ enacted by Netflix are from renewable energy. Here’s the key problem: it is actually an extremely questionable thing, to use grid power partly sourced from fossil fuel plants, and then claim it’s 100% zero emissions due to some contractual action.

The physical reality is that on a grid, you have a bunch of generators and a bunch of consumers. The emissions of the consumers add up to the emissions of the power generators. If you do a deal with a wind farm to say an electron they put onto the grid goes directly to you, you didn’t really capture that little unit of power yourself. Even if you pay to build your own wind farm and attach it to the grid, it’s still all being poured into one big pool – and every person taking identical buckets out of that pool is telling different and conflicting stories about what’s in the water.

Think about it this way: imagine Netflix pays to build its own extra wind farm to power its new data centre, and claims to be running on 100% renewable energy. But another power consumer on the grid just uses the new grid average – double-counting that wind farm’s reductions. The end result: the real emissions end up being far greater than what those companies report on their accounts. And new wind and solar that should have been cutting into coal and gas power just end up filling new data centre demand instead.

If you pay for a certificate – even if you pay to build your own wind farm – you are still never really using a sole source. And clever accounting does nothing to change the physical reality of emissions pumped into the atmosphere.

It’s seen as generally a good thing when a corporation adding mountains of new demand to a grid pays for their own extra clean power, but to me, it smacks of a sort of unpleasant societal disconnect. The grid is a single machine made up of a collective; both on the supply and the demand side. To add new demand, and then shrug it off by saying ‘no problems: we met that new demand with clean sources’ betrays the collective effort to eliminate fossil fuels from grids.

Consider Texas, where data centre demand (from Bitcoin mining and other sources) has grown significantly. It’s easily the central hub of the US’ wind and solar growth: and emissions have not fallen for a long time.

Most of Netflix’s ‘avoided emissions’ stem from a mix of bad-to-worse accounting measures for how they consume electrical energy.

Recent videos on the company’s sustainability efforts mostly features batteries, EVs and hydrogen for remote power, but these are a tiny fraction of their total “avoided emissions”, with most coming from renewable energy agreements of some kind:

Notable in there is the measly 75 tonnes of avoided emissions from EV usage. At a rough calculation (752 MTCO2-e from cars, 328.3m population), that’s the annual emissions from the car use of about 35 average Americans. Netflix has more than 12,800 employees.

Netflix have set themselves a target of reducing these scope 1 and 2 emissions by 45%, by the year 2030. But in their report, they’ve included a weird “projected emissions” thing that makes their actions look visually significant – there is zero information on where this baseline comes from, or how it was developed. But taking their word for it: it shows Netflix plans to massively ramp up its energy consumption, and mostly use dodgy power accounting to paper over it in their emissions data.

The single most important first step here should be accurately accounting for the problem. It can’t be fixed until it’s measured. But this combination of on-paper clean energy deals and a plan to grow power consumption significantly suggests Netflix is looking for the easiest way out.

Netflix’s emissions intensity cheat

When a company like Netflix uses an external service as part of its normal business, that service has emissions. Like an employee catching a plane, or another production company making a TV show, or their content being hosted on servers owned by another company.

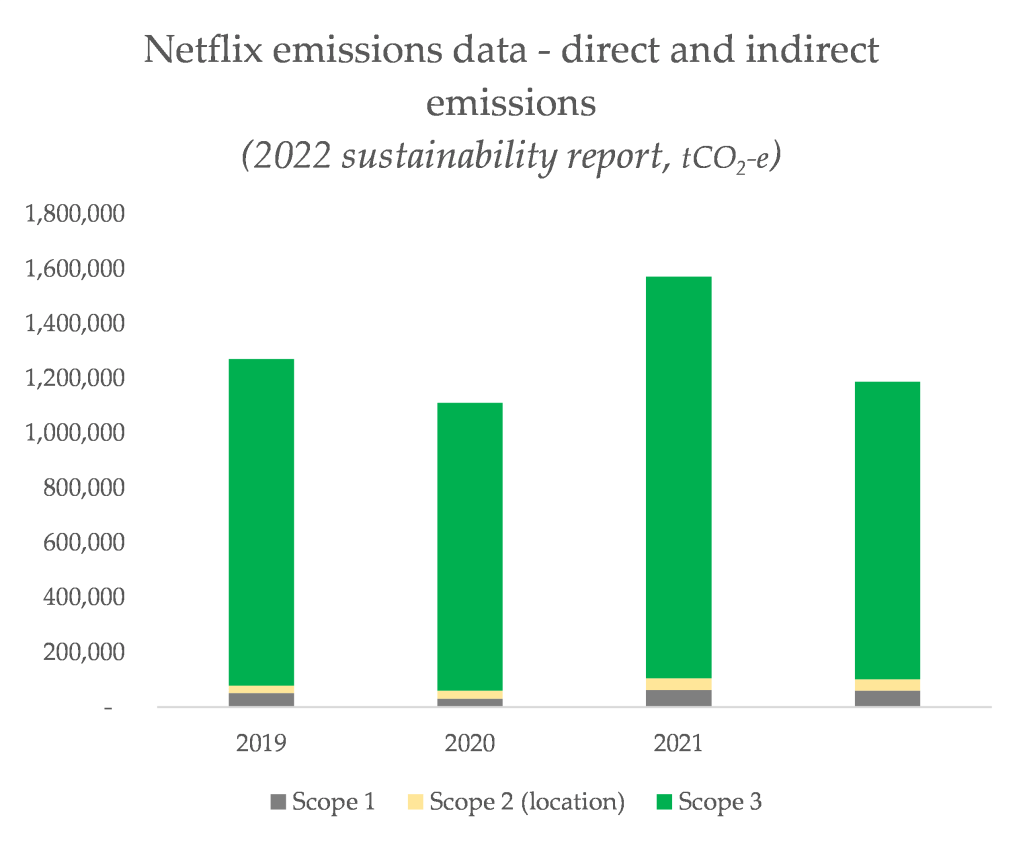

These ‘scope 3’ emissions are massive, compared to the direct emissions discussed above:

Some of this comes from them paying other production companies to make shows, and some comes from their content being hosted on Amazon Web Services (AWS). By what ratio? We’ll never know: Netflix doesn’t disclose any more details beyond some vague statements.

They do explain the drop from 2021 to 2022: a return to normal production volume after the post-COVID boom, and Amazon buying a bunch of renewable energy certificates.

“In 2022, AWS reported via their customer carbon footprint tool that our carbon footprint was reduced by approximately 98% compared to last year. This is due to AWS’s renewable energy usage and purchasing, and energy efficiency initiatives”, Netflix said in their report. Given that nugget, and the reduction, we can infer that around 20% to 30% of their scope 3 emissions relate to streaming. And it got wiped off their accounts due to the aforementioned renewable energy certificates.

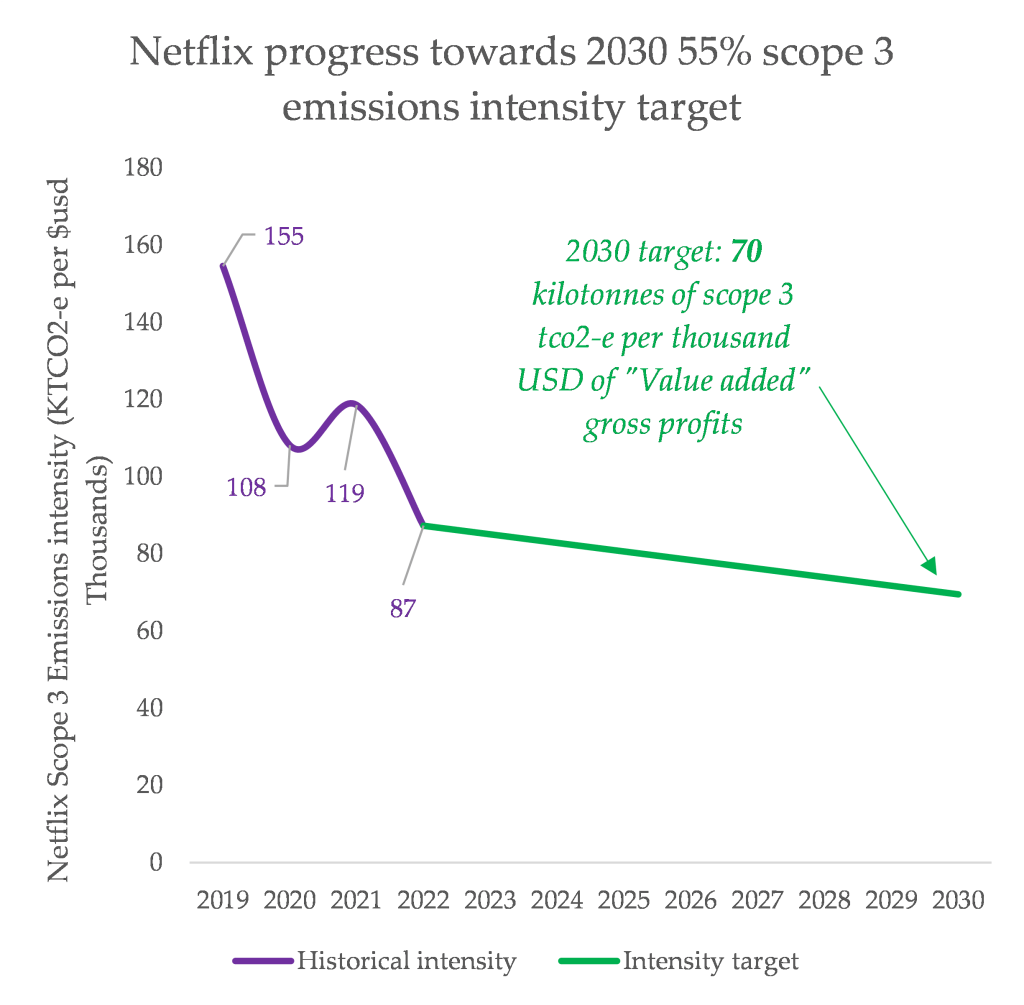

Putting that aside – Netflix has a responsibility to exercise its power and influence to help reduce emissions it enables. This year, they announced their first scope 3 target – a 55% by 2030 reduction (from a 2019 baseline as far as I can tell – I emailed them to check and got a canned response) not in absolute emissions, but in “intensity”.

They measure this in megatonnes of emissions per million USD of “value added”. This is, they say, “synonymous with “Gross Profit,” derived from subtracting “Cost of Revenues” from “Total Revenue” for the business, per our public financial statements”.

Listen to me: you don’t need to understand any of those words. Just recognise this: the target is not to reduce how much they dump into the atmosphere, it’s to reduce how much they dump per dollar of cash they take home.

Here’s something odd: they don’t include this metric graphically in the report, like they did for direct emissions above. And in my experience, every exclusion is intentional.

So I got the ‘gross profit’ figures (from here and here), and calculated this intensity metric. Netflix have made a lot more money, and their emissions haven’t changed much, so the ‘intensity’ has fallen a lot since 2019:

That’s quite the drop in intensity, for almost zero change in emissions!

Remember, their target is a 55% drop by 2030. So how much of the target have they already met?

Oh. right. This is why they didn’t include a progress chart for scope 3, like they did for 1 and 2. Netflix have progressed four fifths of the way towards their 2030 scope 3 emissions reductions target, in the year they set the target, while barely having changed their scope 3 emissions.

All they need to hit their target within a year or two is to make more money while only ensuring scope 3 emissions don’t rise too much. Which they can easily do with unbridled purchasing of renewable energy certificates from their third-party providers. All while failing to disclose any detailed breakdown of these emissions.

The simple question with any climate target: “is this driving real change”? How could a target like this drive any meaningful change at all? How could it hold Netflix accountable? The simple answer is that it absolutely doesn’t do any of these things.

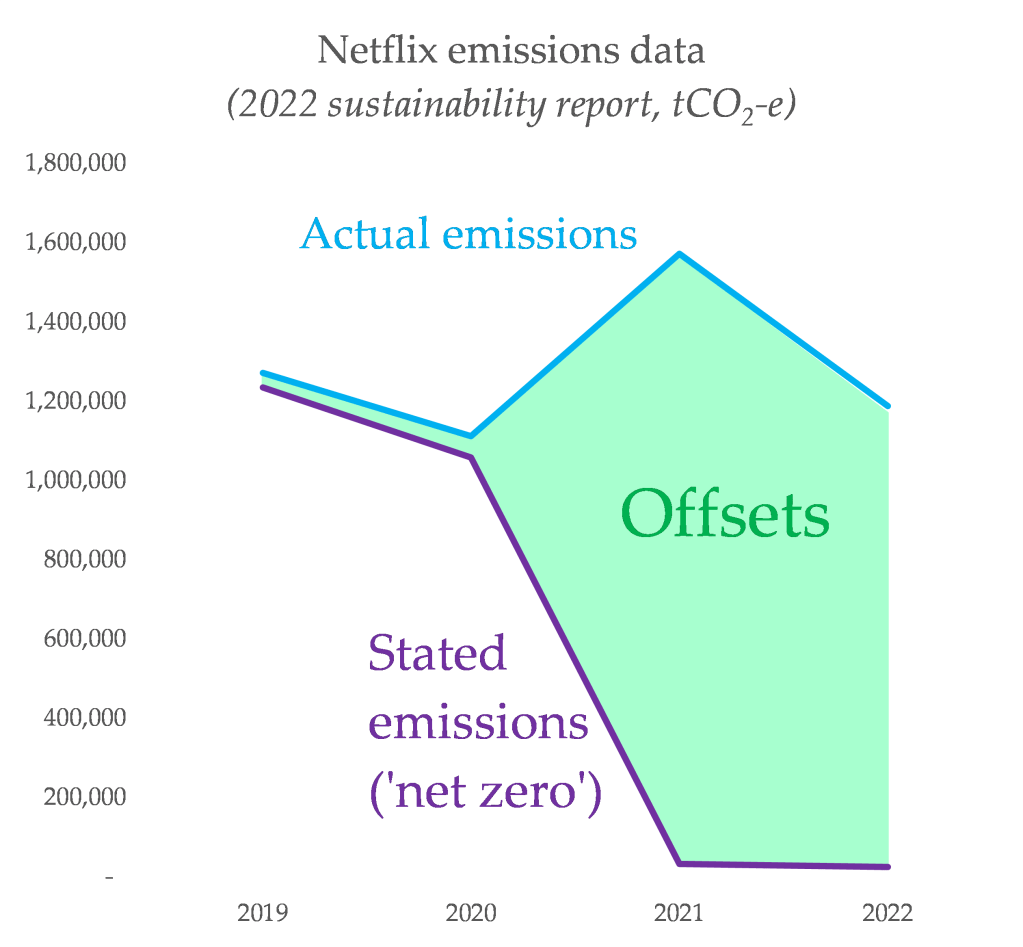

Netflix isn’t net zero

We’ve gone through Netflix’s self-admitted greenhouse gas impact, but incredibly, Netflix claims to have basically already achieved a state of having no impact on Earth’s climate whatsoever:

It’s a little hard to understand this, because from their own reporting, they were already at “net zero emissions” by the end of 2021, so it’s not clear why this ‘starts’ at the end of 2022. Their most recent statement, from March 2023, says “To supplement this decarbonization work, we delivered on our promise to net all remaining emissions to zero by investing in the power of nature to retain and capture carbon”.

Well – it’s not really a ‘supplement’: offsets are doing literally all of the work. It is 100% net, 0% zero.

When Netflix say they’re ‘investing in nature to store carbon’, that’s flat-out wrong for the majority of their offsets. About 65% of offsets bought in 2022 relate to avoiding greenhouse gas release, rather than actively removing carbon. The hypothetical best case with ‘avoided emissions’ is that climate damage is kept at the current level rather than increasing even further.

The reality is that this type of offsets make things measurably worse. There is a financial incentive to sell as many cheap, low-quality and dubious offsets as possible in this industry, meaning they don’t even do what it says on the tin. That is to say: Netflix keeps emitting, and these projects don’t even ‘counterbalance’ that with reductions elsewhere. Everyone keeps getting worse.

Netflix featured in a recent investigation published by Source Material, the Guardian and Die Ziet for exactly this reason. Projects they’d bought offsets from turned out to have exaggerated how much emissions were being avoided.

Removing carbon is better, right? Projects marked as ‘removal’ involve sucking carbon into newly planted trees. But some of these involve trees simply being grown in places where they were before. Does growing that tree back undo the diesel generator spewing out greenhouse gases on the set of Stranger Things? No, it does not.

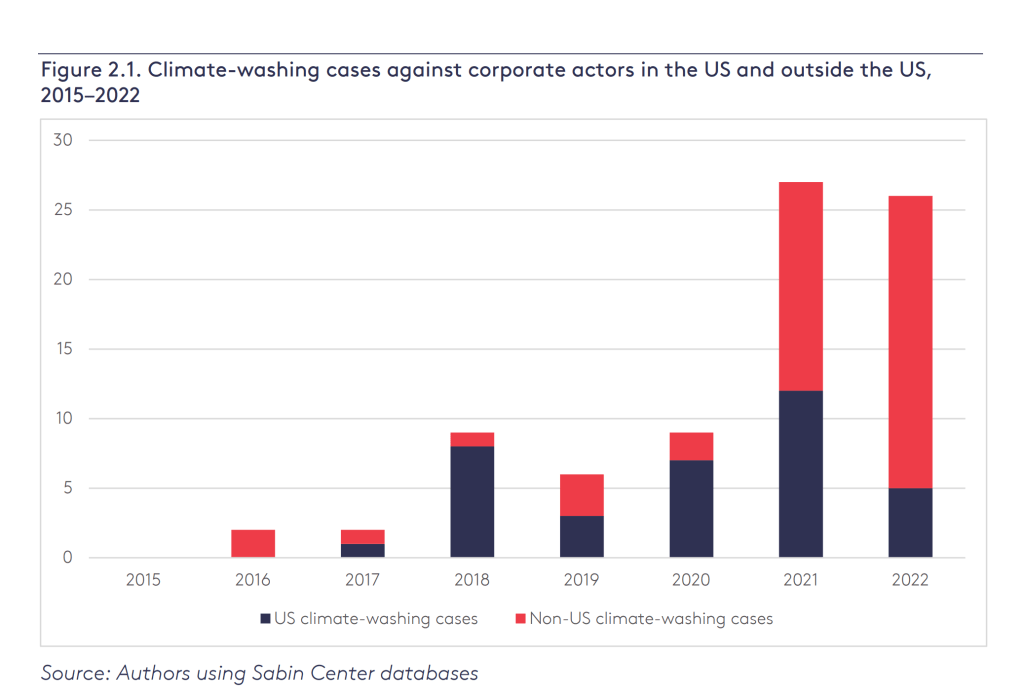

Netflix has a massive climate impact. It is deceptive or dishonest to underplay that impact, but to claim that it’s entirely non-existent is so bad that it’s attracting legal consequences. False claims of “net zero” or “carbon neutrality”, however they’ve built, are being taken to court in increasing numbers:

Netflix demands huge volumes of electrical power, and doing that isn’t a neutral process. Yet they are not taking responsibility for being an expanding energy user. A related example of rising power demand on grids is the energy-hungry process of training machine learning tools; something that’s causing rising consumption from companies like Microsoft and Google.

I mention it because it features in that Black Mirror episode. The plot revolves around an automated script generation tool that blindly generates content for the fictional streaming company’s viewers. In reality, at the same time as writers in Hollywood engaged in a massive and painful strike to fight back against plagiaristic automation, Netflix listed a $900,000USD AI job on their site.

You can do the bad thing, and continue to do it, as long as you ironically declare that you’re aware that you’re doing it. Bo Burnham does this in his popular Netflix special, Inside. It was irritating, and defeatist.

Well, that’s us: millennials. We know what we’re doing, and we’re good at talking about it and even making fun of ourselves for it. But we’re terrible at actually changing the system. We’re right to scoff at boomers and their cruises for being worse, but we’re bad in our special, dry, self-critical way.

Netflix is pioneering ironic, millennial greenwashing, blended with the bog-standard corporate net zero shenanigans. The end result: a huge swathe of missed opportunities, framed as if it’s world-leading climate action.

Thanks for this terrific work, Ketan. Kind regards, Toby Miller

LikeLiked by 1 person

du hund

LikeLike